Everyday Philosophy: Were your parents right to make you “clean your plate”?

- Welcome to Everyday Philosophy, the column where I use insights from the history of philosophy to help you navigate the daily dilemmas of modern life.

- This week we meet Maria force-feeding herself because of the voices in her head.

- Along the way, we look at Confucius and Ayn Rand via Jesus to help resolve her dilemma.

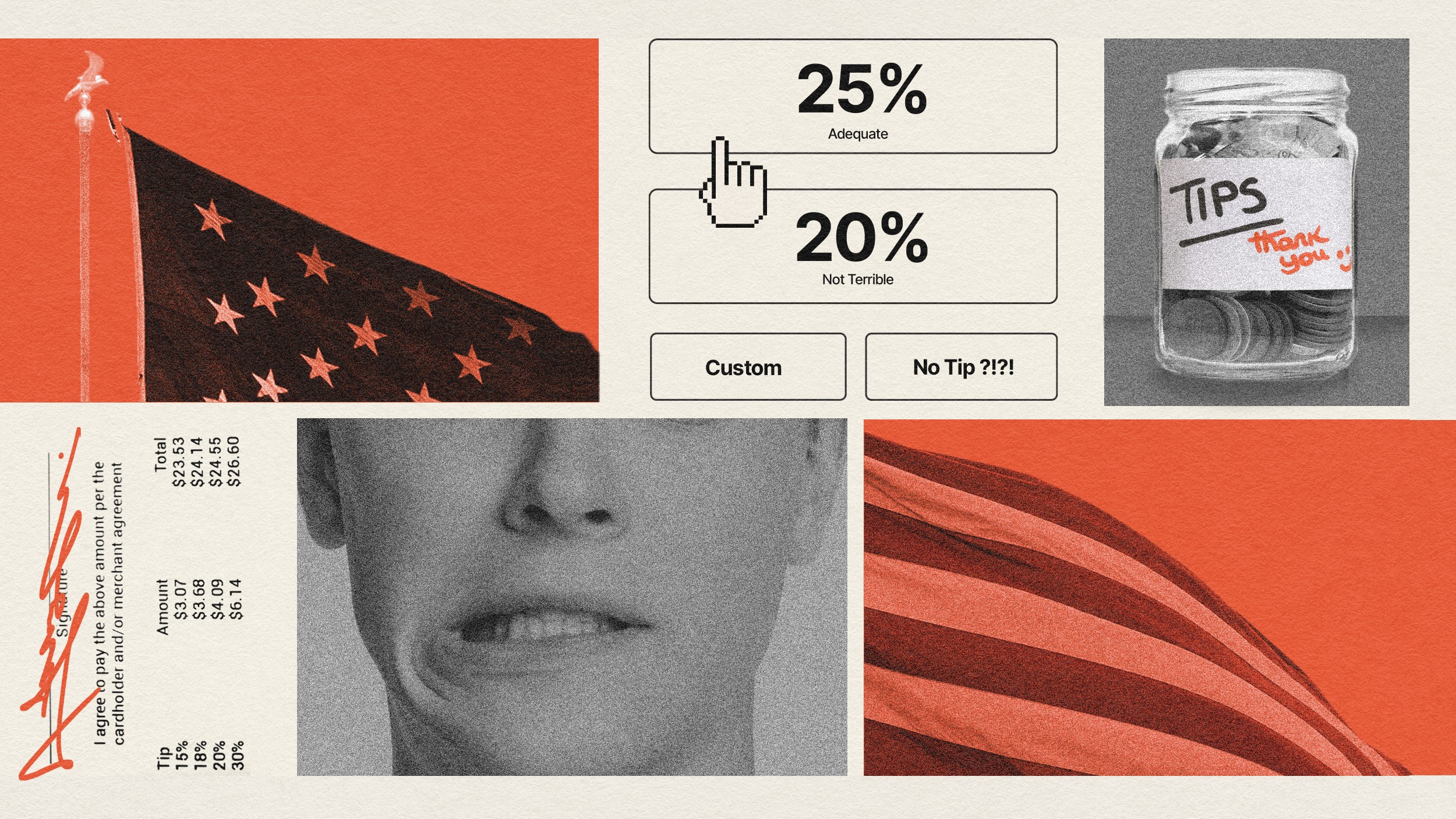

I don’t feel like eating the last few bits of my meal because I am very full, but I do so out of obligation, a mixture of the fact that I have paid for it and that “there are people starving,” like my mother would tell me. Do I finish my meal out of guilt, even if it is unpleasant?

– Maria, US

I like this question because I’m pretty sure it’s going to get the commenters out. One thing I’ve learned from many years of public philosophy is that there is a certain kind of person — a lot of people, in fact — who knows the answer. They’re aggressively and condescendingly sure of everything. “It’s common sense,” they might say, or “What a stupidly obvious question,” they will write. And, with 30 words, they’ll solve philosophy’s greatest questions. The trolley problem? Obvious. What is beauty? Too easy. God? Don’t get me started.

Such a person might tell Maria not to bother: Just eat as much as you want and no more. Don’t get tied down by emotional baggage and that antiquated relic that is “guilt.” Live your best culinary life.

But, of course, that’s not the whole story. Many people do care about guilt and obligation, willing to subject themselves to small and everyday acts of self-harm because of their mother’s voice in their heads. This is not a simple question because, at its core, it’s a clash of values. It’s about living according to your upbringing, having a self-regulating moral code, and making rational, albeit egoistic, decisions.

To exaggerate the point to folklorish levels, I’m going to call upon two radically different philosophers representing both sides. To expose the notion of ritual propriety, we’ll look at the Confucian philosopher Wei-ming Tu. And, to smash propriety with an egoistic sledgehammer, we’ll look at Ayn Rand. Yin and Yang. North and south. Chalk and cheese. Let’s get polemic.

Rand: The virtue of selfishness

At the risk of offending everyone invested, I’ll start by comparing Rand to Jesus. In the Christian Gospels, there is a famous story where Jesus is caught picking some grain on the Sabbath — technically, an act of labor — and according to Exodus, that could have been punishable by death. But Jesus turns on his accusers and says, “The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath.” His point is that the spirit of the law is more important than a legalistic, pedantic reading of the letter of the law. What was the Sabbath for? Was it to catch people out pointlessly or allow rest and worship?

In The Virtue of Selfishness, Rand makes a similar anti-legalistic point. As she puts it, “There are two moral questions that altruism lumps together into one package deal: (1) What are values? (2) Who should be the beneficiary of values? Altruism substitutes the second for the first.”

Rand argues that so many supposed “values” today actually serve to stifle our “moral existence.” We bow to various virtues of “justice,” “fairness,” and “equality” when they make us suffer. We live according to values that “permit no concept of a self-respecting, self-supporting man.” For example, any system that views “an industrialist who produces a fortune and a gangster who robs a bank as equally immoral” is a broken one.

For Rand, we are caught in two separate traps: cynicism and guilt. We are cynical about these values and rarely, actually, act upon them. We stick to performative social media posts and sing the right lines. But we are guilty because we dare not reject these values. We dare not voice an alternative position.

For Rand, then, Maria’s guilt is actually a transfer of guilt from her own cowardice. She knows that eating her food is ridiculous. She knows that acting on the voice of her mother is masochistic insanity, but she does it anyway because those are the values of our society. For Rand, put down the fork, put down those assumed values, and just walk away.

Tu: Society as a process of humanization

Rand often refers back to a “natural” state of mankind. It’s natural to be selfis, care about your own family, and want as much as you can get. The problem is that this “naturalistic fallacy” often fails on several counts.

First, many things we do are unnatural, and yet most of us do them — antibiotics, flight, and contraception, for example. Second, why does something being “natural” make it “right”? Confucianism takes up this second question, agreeing with the general claim that humans can often be egoistic and selfish. But while we are biologically driven to care for ourselves, there’s a difference between what we are and what we can be. As Tu puts it, “despite his ontological self-sufficiency, for man to become a fully actualized human, [he must] make sincere attempts to harmonize his relationships with others.”

According to Tu’s reading of Confucianism, there are four developmental stages to self-cultivation: our personal life, our family life, our country, and our world. Only the first, and most basic, allows us to withdraw from the world into a selfish hermitude. And so, “in a practical sense, self-cultivation is an unceasing process of gradual inclusion.”

How does this relate to Maria overstuffing herself with food? Well, implicit in her question are three higher-order degrees of self-cultivation. First, she cares about herself; she has paid for the food. Second, she cares about filial propriety; she wants to live according to the values her mom gave her. Finally, she cares about the world; she is bothered by the presence of starving children. So, for Tu, Maria is not wrong at all. She’s a higher version of humanity.

The wood from the trees

Coming full circle, I feel I owe an apology to my imaginary commentators. Because, if I’m honest, it’s true that sometimes philosophy gets carried away. When you spend hours reading George Berkeley, you can believe the world doesn’t exist, and when you write an article about Confucius, it’s easy to get swept up in your own rhetoric. But let’s zoom back to Maria: Is there really anything noble or admirable about her self-force-feeding expensive food to the point of vomiting because it’s an act of self-cultivation? Both common sense and restaurateurs say no.

So, perhaps the middle way here is to accept that Rand wrongly emphasizes a dubious account of human nature. We are not all red in tooth and claw from our daily Hunger Games cage match, but rather we are rational, moral, and kind people, just as often and just as “naturally.”

But I would argue, as would almost all sages in history, that the rational and sensible path is not an extreme one. It’s one of moderation. So Maria should care about her parental values. She should care about world hunger. But, in this tiny instance, she should care about herself too. You don’t need to set yourself on fire to make other people feel warm.