What happens if you deep fry a frozen turkey?

- One of the most American of traditions is cooking an entire turkey on Thanksgiving Day, celebrating hundreds of years of our country’s history with a harvest/feast holiday.

- While there are many ways to cook a turkey, with roasting it in the oven being the most common, a clever, fun, and delicious alternative to the mainstream is to brine and then deep fry yours.

- Unfortunately, there are tremendous hazards associated with deep frying a turkey, and the worst thing you can do is place a non-completely defrosted turkey in the deep fryer. Here’s why.

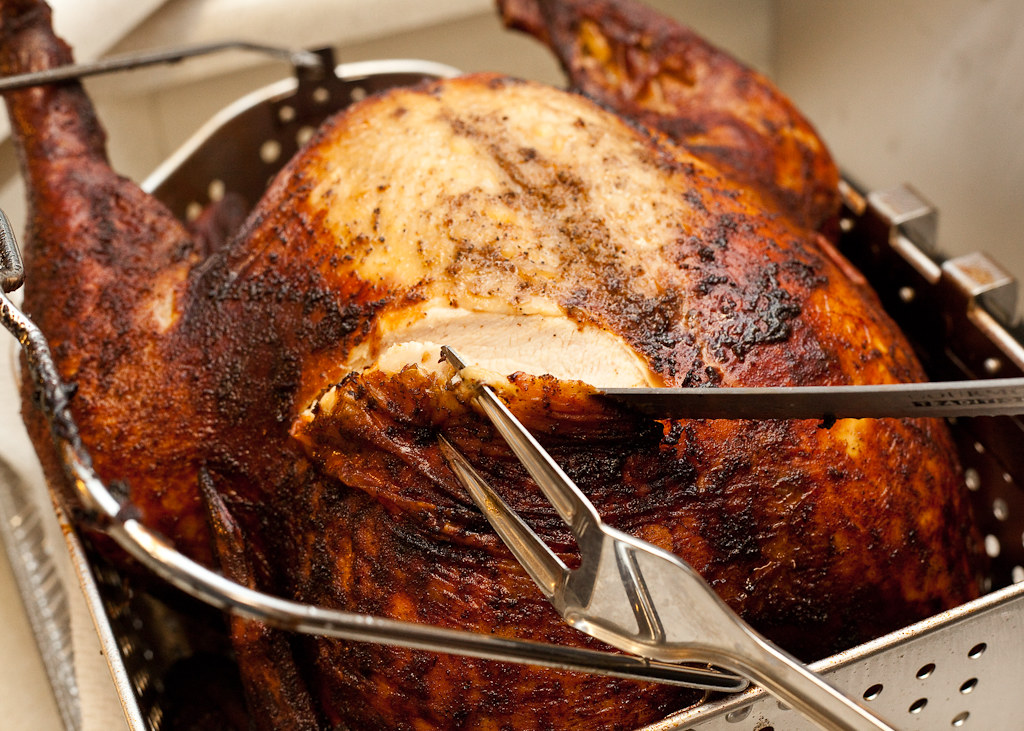

One of the most enduring traditions in the United States is the Thanksgiving turkey. The one-time contender for the official bird of the nation — advanced even by Benjamin Franklin over the bald eagle — has been served at homes across the nation for centuries, with an estimated 46 million turkeys consumed nationally on the fourth Thursday of every November. Most frequently, the modern American family purchases a frozen turkey, and then begins thawing it days before the actual event. While many Americans roast their turkey in the oven, a popular trend in the early 21st century has been to deep fry your turkey: a fun production that cooks a turkey very quickly (often in just 45 minutes, as opposed to four hours or more for a 15-20 pound turkey) and gives it a delicious, unique flavor.

However, many who cook turkeys as part of our annual tradition run into a dilemma: they haven’t pulled their turkey out of the freezer early enough. What should one do with a still-frozen (either completely or partially) turkey? Turkeys normally require three or more days to fully defrost in the refrigerator, so how do you salvage it? You can try:

- thawing it in very cold, continuously-changed water,

- defrosting it in the microwave (if your microwave is larger than your turkey),

- or roasting it for an extra long time at a significantly lower-than-normal temperature in the oven.

What if you’re determined, however, to deep fry your turkey? If your turkey remains even partially frozen, it’s a recipe for disaster. Here’s the physics of why you must never deep fry a frozen turkey.

Deep frying is a simple method for cooking with lots of benefits, both time-wise and deliciousness-wise. Unlike the traditional oven-roasting, where heated air externally cooks whatever you put into the oven from the outside, deep fryers work by submerging your food into an extremely hot liquid: oil. Whereas oven-cooking runs the risk of drying out your meat around the outside while taking an extremely long time to cook the interior meat nearest to the bones, deep frying — because the water-based liquids inside the turkey are repelled by oil — keeps those juices from dripping out. As a result, all of the meat stays moist and juicy inside a deep-fried turkey, while it fully cooks in only a fraction of the time compared to roasting.

But deep frying requires a deep fryer large enough to hold an entire whole turkey, and unless you’re making Thanksgiving from the comforts of a commercial kitchen, odds are that you don’t have one large enough for the job. The way most people work around this is to:

- set up a large pot,

- full of oil,

- in a well-ventilated area (such as outside),

- where you can put a heating element of substantial power (i.e., a gas-powered device) underneath it.

Heat the oil to the desired, sufficiently high temperature, then slowly lower your pre-seasoned (or pre-brined) turkey into it, and once it’s fully immersed, just let the deep fryer do the work.

There’s a danger here that might jump out at you: when you have oil and a gas-powered fire together, there’s a big, big risk of starting an uncontrolled blaze. This is no rarity; according to the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), Thanksgiving is the most dangerous day of the year for cooking fires, with an estimated 1610 home cooking fires reported on that day in 2022. Whereas earlier reports warned of the dangers of deep frying a turkey in oil, citing 5 deaths, 60 injuries, and 900 lost homes per year a decade ago, the NFPA now recommends against deep frying your turkey entirely, stating:

“Turkey fryers that use cooking oil are not safe. These fryers use large amounts of oil at high temperatures, which can cause devastating burns. If you want a fried turkey for your Thanksgiving meal, purchase it from a grocery store, restaurant or buy a fryer that does not use oil.”

While deep frying a turkey in oil may never be 100% safe, there are four basic safety precautions that can make it much, much safer for the average homeowner.

- Make sure that the oil level is low enough that even once the turkey is completely added to the pot, the oil won’t overflow, with the oil level remaining at least a few inches from the top.

- Make sure the setup is stable: on level ground, away from other flammable materials, and preferably outdoors as well, to minimize the risk of any potential mishaps.

- Make sure you immerse the turkey slowly into the oil, lowering it gradually from a hook that keeps your arms and hands far away from any potential splatter.

- And — perhaps most importantly — make sure that the turkey is completely thawed, and not still frozen in any way.

The first two steps may be obvious, but the third and fourth ones are more subtle. Clearly, if you are going to have an open flame or an extremely hot heating surface, putting a flammable material like cooking oil directly onto it is a near-certain way to start a grease fire, so ensuring that the oil-filled pot doesn’t overflow is critical. Also, if a very hot surface or an open flame tips over, it has the potential to start a very large fire, particularly if it’s inside or near to a home or other flammable structure. But even taking these two precautions isn’t necessarily — on their own — enough to avert a potential disaster.

We often say that oil and water don’t mix, which is true, but most of us don’t necessarily remember that oil is less dense than water; a turkey, like most birds and mammals, is more than 50% water, and will sink if placed in oil. If that oil is very hot, and a recommended oil temperature for deep frying a turkey is either 325 °F (163 °C), 350 °F (177 °C), or 375 °F (190 °C), that water is going to boil in very short order, changing phase from liquid to gas instantaneously. If that water is on the very surface of the oil, it’s not much of a problem; the water will turn to steam and only tiny amounts of splatter will result.

But if that water is underneath the oil, when it turns from liquid to gas, its volume expands tremendously: by a factor of about 1600. This rapid expansion, if it occurs when the turkey (or any water-containing object) is submerged in the oil, will easily cause the oil to spill over the edge of the pot and onto the heating element below: the exact recipe for a fire that we sought to avoid. This is why it’s so important, when you first put a turkey into the deep fryer, to immerse it slowly and gradually.

The instant the turkey hits the oil, the water content of the turkey will begin to boil, as that typical oil temperature of 350 °F (177 °C) is well above the temperature at which water boils. This means that the water, upon coming into contact with the oil, will begin boiling almost instantly, turning into steam.

Lowering the turkey slowly and steadily into the oil is how you keep this from becoming a problem. Only the external surfaces of the turkey — the components that were in contact with the air just prior to touching the oil — will immediately boil, which will give off a tremendous amount of steam and rising heat. (This is why it’s important to make sure your hands aren’t, say, holding the turkey legs directly as you lower its body into the oil!) So long as you don’t lower the turkey into the oil too quickly, the water on the surfaces of the turkey will turn to steam, while the hydrophobic nature of oil repels the water inside. The turkey, once completely submerged, will cook quickly and safely, as the interior water only turns to steam gradually. Overall, the exact cooking time required depends on the oil’s temperature and the turkey’s total weight, but you can end up with an absolutely delicious turkey on the inside.

But what about the deadliest scenario of all: if your turkey is still frozen? This is a problem, as even if you ensure that your turkey gets lowered slowly and steadily into the oil exactly as before, you’re still all but guaranteed to start an uncontrolled fire. Here’s the physics of what happens, and as you go through the steps, you can easily see for yourself that this very, very rapidly is going to result in disaster.

The instant the turkey hits the oil, the solid ice has to begin melting before it can become water. Once the ice melts, you’ll have exactly the same situation as the earlier scenario: the water, surrounded by large amounts of ultra-hot oil, will heat up rapidly, boiling and turning into water vapor (steam) almost instantly.

If you were to merely drop some cubes of ice into a deep fryer filled with pre-heated oil, you’d probably be fine. Ice is not only less dense than water, but is less dense than oil, too. (By only about 2%, but that’s enough!) The oil that touched the ice would rapidly melt it, heat-and-boil the now-liquid water, while only kicking up a few drops of oil into the air. (This is part of the reason why deep fryers have lids!)

However, a turkey carcass, like the carcasses of most animals (that lack a large amount of air trapped inside of them), have an overall density that’s much greater than oil. Even if the turkey is frozen, it will still sink to the bottom of a bath of oil.

This is where the key problem arises. If you have a frozen turkey and begin lowering that turkey into a very hot bath of oil, here is — step by step — what’s likely to happen.

- The ice that first touches the oil will begin to melt, then that water will rapidly heat and begin to boil, all near the oil’s surface, and then the steam will rapidly rise.

- As you continue to lower that turkey into the oil, more and more of the frozen turkey — after all, most of the water in it is ice — will have that ice turn to water, not only at the oil’s surface, but now beneath it as well.

- But water is not only denser than ice, it’s denser than oil, too, so this newly-created liquid water will find itself well beneath the oil’s surface.

- That water is now completely submerged in very hot (remember, at least 325 °F/163 °C) oil, where it will begin to boil and convert to steam, all while it’s still beneath the oil’s surface.

- Ice is about 10% less dense than water, and when it melts-and-then-boils, it again increases in volume by a factor of around 1500: again, a factor of more than 1000.

Because of how much more volume air occupies than water (or ice), this water vapor within the oil will rapidly expand: a near-guarantee to push oil over the sides of the fryer, and onto the flames or heating element below. That is precisely the recipe for a fiery disaster to occur.

From a physics perspective, it’s all but inevitable that catastrophe will now ensue. Once the first splashes of oil go over the side, some of those small droplets will unavoidably land on or near the heating element/open flame. A small droplet will heat up extremely quickly, igniting and bursting into flame itself. With larger amounts of oil nearby, the flame will travel more quickly through the oil than the force of gravity will accelerate that oil down toward the ground; as a result, neighboring droplets will catch fire, resulting in what could best be described as an upward-climbing fireball.

You would think that’s bad enough, as generating a large amount of fire is never a good idea. Add in the fact that many of these setups have:

- a nearby propane tank,

- a nearby house or other flammable structure (doing this in your garage isn’t much better),

- and a vat full of flammable (or, potentially, even combustible) oil on hand,

this can quickly become a house-threatening, life-threatening, or even neighborhood-threatening inferno. Even if you take all of the proper precautions, it’s a very smart idea to keep a fire extinguisher on hand for easy access, just in case you need it.

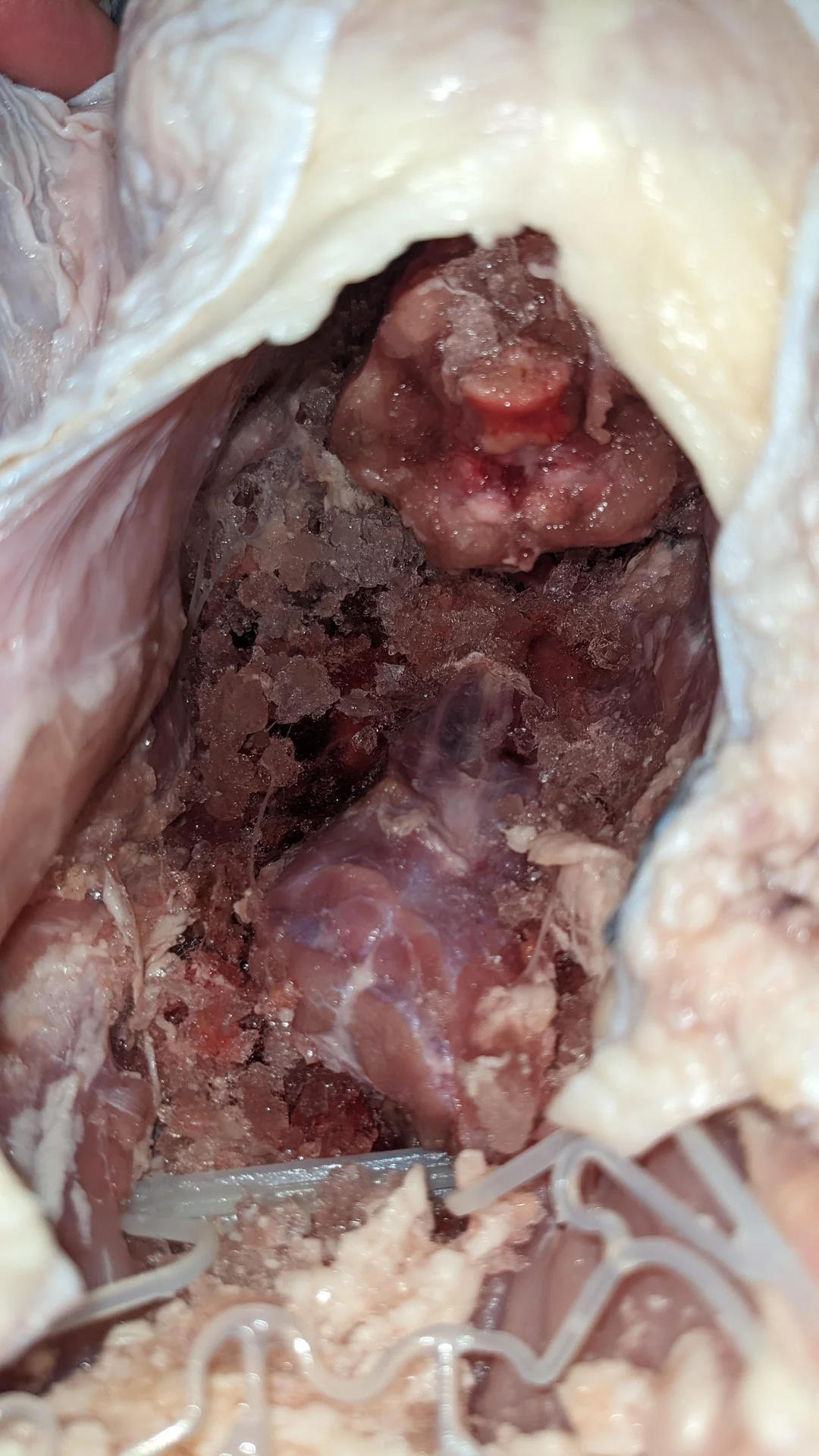

You might think you’d be fine to deep fry your turkey so long as it is partially defrosted: if there are no ice crystals visible on the outside, and if you can “push” at the flesh with your thumb and it feels springy to the touch.

Wrong.

This is not the case at all, and thinking along these lines will only give you a false sense of security. A partially frozen turkey will still have the “ice” problem, and you can find this out for yourself in the most straightforward manner possible: simply by sticking your hand into the inner cavity of the turkey’s carcass.

If you feel any ice crystals at all, that means your turkey is still frozen: too frozen for the deep fryer. The crystals don’t need to be on the outside to create a disaster; the ice simply needs to come in contact with the oil once the turkey is at all beneath the oil’s surface. The same effects that were described earlier:

- where the ice beneath the oil’s surface melts,

- where water sinks in the oil while rapidly getting heated,

- where that liquid water turns to gaseous water vapor,

- resulting in a rapid expansion of its volume,

will once again cause the oil to boil over the sides of the pot and potentially start a fire. This will all occur just as surely and easily with a partially frozen turkey as it would with a completely frozen one.

If you are determined to deep fry your turkey in oil, but you don’t want to start a fire, what’s your best bet?

First, you should absolutely make sure your turkey is entirely defrosted beforehand: 24 hours in the refrigerator for every 4 to 5 pounds of the turkey’s weight should be sufficient. If you want to brine your turkey, do it only once the turkey is already defrosted!

Next, you should measure out the amount of oil you need as follows: by putting the (thawed) turkey into the (empty, unheated) pot, filling the pot with water until it’s at a desired level (with the turkey completely covered but with plenty of space between the water level and the top of the fryer), then removing the turkey. The amount of water remaining in the pot is the level to which you should fill the pot with oil once it’s been emptied and dried. If you’re going to apply a dry rub to your turkey, do it only after making this measurement.

Then, set up your deep fryer on level ground, outdoors, on concrete/pavement, and away from any potentially flammable materials.

Only after that should you fill the pot with oil and heat the oil to the required temperature.

Pat your turkey dry, inside and out, before immersing it in the deep fryer. (Reducing the amount of water you’re going to place in the very hot oil is a really good idea!)

And finally, at last, you can lower the turkey steadily and slowly into the oil: not by directly holding it with your hands, but by using a mechanism that won’t require you to put your body at risk like a metal hook or a fryer-basket insert.

Although the National Fire Protection Association recommends against it, you can still deep fry a turkey in oil for Thanksgiving, and it can be done relatively safely. Yes, you can safely apply a dry rub. Yes, you can brine your turkey beforehand. And yes, you can safely deep fry an entire fully thawed turkey so long as you follow the proper procedure. When dealing with extremely hot oil, be respectful of the fact that it can burn you severely. Wear long pants and long sleeves (that cover your extremities), as well as the always-necessary oven mitts and close-toed shoes. You may want to consider protecting your eyes as well, as tiny drops of superheated oil — even the drops that result just from splatter — can cause burns and scarring that may endure for a lifetime.

As spectacular as a large grease fire is, it’s not something to be courted. Your family, your neighbors, and your local fire department will all be thankful that you didn’t burn yourself or your property or others on this celebratory occasion. No matter how you enjoy this holiday or any other turkey-cooking event (fun fact: Christmas Day and Christmas Eve are the 2nd and 3rd most dangerous days of the year for home cooking fires), if you’re going to do it, make sure you do it safely and responsibly. That means learning the simple lesson that no one should ever test out for themselves: you must never, ever deep fry a still-frozen turkey.