Excess is Not a Modern Problem

Consider the story of the wealthy New York banker and the Greek fisherman.

While vacationing in Greece, the banker meets a Greek fisherman and asks him how long it takes him to catch his fish. “Only a little while,” the fisherman says. The banker responds: “So how do you spend the rest of your time?” The fisherman replies: “I play with my children, take siestas with my wife, Maria, stroll into the village each evening where I sip wine and play cards with my friends.”

The banker, a Harvard MBA, scrutinizes the fisherman’s business plan and encourages him to fish longer and sell directly to the processor instead of to the middleman; this way, he can generate more profits and control distribution. “To do so” the banker tells the Greek, “you will need to move to New York to run your enterprise. If all goes well, you will eventually sell your IPO and make millions.”

“Then what?” the fisherman asks.

“Then you can retire so you play with your children, take siestas with your wife, Maria, stroll into the village each evening and sip wine and play cards with your friends.”*

This parable—ostensibly a critique of modernity—shows itself in antiquity. Montaigne retells the story of King Pyrrhus, who was planning to march into Italy when his counselor, Cyneas, expounds the inanity of his ambitions.

“Well now, Sire, what end do you propose in planning this great project?” – “To make myself master of Italy,” came his swift reply. “And when that is done?” – “I will cross into Gaul and Spain.” – “And then?” – “I will go and subjugate Africa.” – “And in the end?” – “When I have brought the whole world under my subjection, I shall seek my repose, living happily at my ease.” Cyneas then returned to the attack: “Then by God tell me, Sire, if that is what you want, what is keeping you from doing it at once? Why do you not place yourself now where you say you aspire to be, and so spare yourself all the toil and risk that you are putting between you and it?”

Let’s translate. It only takes one taste of success to feel vulnerable. You can spend a lifetime traveling in economy, but one trip in business class and you’ll wonder how you endured those tiny seats. Get one professional massage and you’ll start thinking you have chronic back problems. Start paying for taxis and walking a few blocks will seem like hiking a few miles. Drink a “nice” bottle of wine and suddenly “cheap” wine will taste bad, even though research demonstrates zero correlation between price and taste (this includes studies with so-called wine tasting experts). The more you have, the more you have to lose.

As Seneca advised:

Once… prosperity begins to carry us off course, we are no more capable even of bringing the ship to a standstill than of going down with the consolation that she has been held on her course, or of going down once and for all; fortune does not just capsize the boat: she hurls it headlong on the rocks and dashes it to pieces. Cling, therefore, to this sound and wholesome plan of life: indulge the body just so far as suffices for good health.

Psychologists coined the word “habituation” to describe our tendency to adapt to a repeated stimulus. Economists coined an even more cumbersome term—“the law of diminishing returns”—to capture the same idea in financial terms. But Seneca and Cyneas remind us that this proclivity is an enduring theme—present in all milieus.

“If a man does not give himself time to get thirsty, he will never enjoy drinking,” declaimed the fourth-century (B.C.) historian Xenophon, perhaps starting a tradition in Western thought about the perils of abundance. Writing in the 16th century, Montaigne traces a number of expressions, from Tibullus (“If your stomach, lungs and feet are all right, then a king’s treasure can offer you no more.”) to Horace (“Those who want much, lack much”) concluding, wisely, that “nothing cloys and impedes like abundance” and “all things are subject to… moderation.”

Barry Schwartz’ The Paradox of Choice wisely advocates a less-is-more approach, but decision making books that outline choice overload wrongfully blame modernity. The authors of these books deploy cute anecdotal stories (usually manufactured in hindsight) about strolling the aisles of a convenience store and becoming overwhelmed with choice. There are too many brands of Cherries, toothpaste, jeans, ketchup—high school graduates have too many colleges to choose from; menus have too many options. Abundance is of course a hallmark of modernity and it often strains the conscious mind.

But would the ancients be surprised?

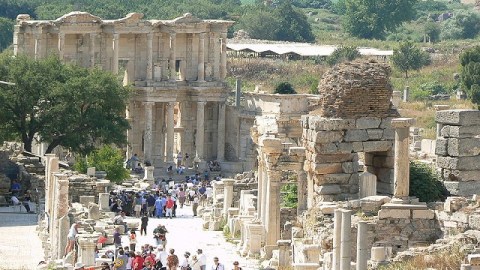

Image via Wikipedia Creative Commons

* I borrowed portions of this story from here.