How to Be an Individual in Age of the Echo Chamber

By BRUCE PEABODY, guest blogger

Last week, we considered how M.T. Anderson’s novel Feed lays out a set of fears about today’s electronic culture and its impact on how we think, interact and develop our moral selves. Anderson voices widespread anxieties about the internet age, but his book is rather short on solutions and hope.

Today’s post proposes that we train our gazes to the 19th century, and the political and social philosophy ofJohn Stuart Mill, in order to search for ways out of Anderson’s dystopian landscape. In particular, Mill’s On Liberty, a paean to an engaged and self-aware individualism, is a valuable complement to Feed, and a promising touchstone for thinking about the fate of our own times.

Even ostensibly free citizens, Mill charges, rely too much on convention, shared ideas, and generic experiences fostered by a “unity of opinion.” When the “customs of other people” dictate our behavior, we cannot achieve “the principal ingredients of human happiness” including “excellence.”

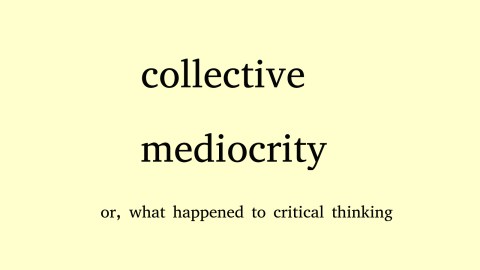

Mill especially feared non-discriminating mass publics. The rise of “collective mediocrity” was exacerbated by the emergence of new media (wide-circulation newspapers in his time) which served only to reinforce uniform, traditional, and unexamined views. In this environment, people’s “thinking is done for them by men much like themselves, addressing them or speaking in their name, on the spur of the moment.” Sound familiar?

Mill’s antidote to all of this is a partly familiar model of robust individualism. We owe it to ourselves (and our fellow human beings) to select our own distinctive lifestyles and ideas, and to share them, ceaselessly, with others.

A person “whose desires and impulses are his own—are the expression of his own nature, as it has been developed and modified by his own culture” can be said to have “character.” Such people challenge and elevate their society. The most innovative are “persons of genius” (the phrase resembles an idea of Lincoln’s) who expose us to “new practices” and ways of living, even as the more hidebound members of society dismiss them as “wild” and “erratic.”

In Feed, the outsider Violet embodies this convention-upsetting figure. Her boyfriend, the sporadically sentient Titus, identifies her as the most “amazing” person “even if she was weird as shit.” Violet in turn, offers Titus what passes for the ultimate compliment in the world of the feed:

You’re not like the others. Yousay things that no one expects you to. You think you’re stupid. Youwant to be stupid. But you’re someone people could learn from.

At his best, then, Titus is Millian—he is capable of individual excellence which bucks the uniform idiocy of his peers and, in turn, improves the quality of life of those around him.

Of what use are Mill’s ideas for 21st-century browsers, bloggers, and tweeters?

Mill urges intellectual cacophony: a loud, energetic, personal, and often contentious set of conversations about who we are and what we value. In this regard, his political theory anticipates a public space resembling some aspects of today’s online communication. There is no vaster “marketplace of ideas” than the bazaar of the internet. Here is a brief Millian guide to browsing the web:

1. Be self-conscious in thinking about why you are seeking out information. Are you genuinely curious about a topic and anxious to find out more? Or are you seeking to massage or reinforce your pre-existing views?

2. Sample widely different viewpoints and beliefs, including those that deeply challenge what you hold most dear. If you are a died-in-the-wool liberal, look beyond The Nation to smart, conservative commentators like David Brooks of the New York Times, George Will of the Washington Post, or the libertarian-inflected voices of the Vokokh Conspiracy. If you’re a Fox News junkie, try MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow on for size. If you find yourself spitting your coffee over your keyboard at these names, that’s fine, so long as you are able to identify someone who fits the bill. If you can’t, you’re the problem.

3. Be aware that the suggestion to search out the views of intellectual enemies may backfire if you aren’t honest with yourself. Reading blog posts by especially laughable or obnoxious “opponents” (or just people whose views you detest) simply to stoke your ire against them is fun but counterproductive. The test is if you can be sympathetic to (some of) the positions and beliefs of your real or imagined adversaries—perhaps so sympathetic you even—gasp—find yourself changing your own views.

4. Be humble. Remember that you’re fallible too, just like Rush Limbaugh and Al Sharpton. And even if you can’t fathom why millions of Americans voted for the “wrong” presidential candidate or espouse beliefs you can’t stomach, keep in mind many of them feel the same way about you. Find ways to engage them and their ideas online or in person.

5. Finally, take advantage of the proliferating research on the myriad arational and irrational factors that shape human cognition and choice. Use these insights to inform your approach to consuming news and information, and to keep you on guard against your own idiosyncrasies and biases.

None of this is easy, of course. Titus notes that with the electronic feed “you can be supersmart without ever working.” Mill’s countervailing vision is that we are unlikely to remain “supersmart” (since even our most cherished beliefs are in constant jeopardy of being toppled), and our (informed, skeptical, curious) lives will certainly entail a tremendous amount of industry.

But as both Feed and our daily struggles to navigate our (inter)connected world make clear, these issues are trenchant and their underlying stakes are high. Seemingly private choices, increasingly transmitted through online purchases, chats, texts, and posts, do much to define who we are as individuals and as a people. And as Mill reminds us, it “really is of importance, not only what men do, but also what manner of men they are that do it.”

Bruce Peabody is a Professor of Political Science at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Madison, New Jersey. He is currently writing a book about American heroism.

Read the first installment of Professor Peabody’s essay here.

Related content in Praxis: