My Lesson From Macau: Why Creativity Starts With Awe

“Hello China!…… there are just so many of you.” Stefani Germanotta, better known by her Queen-inspired moniker, Lady Gaga, made that appeal to 15,000 screaming teenage Chinese girls in a large concert hall in Macau in the summer of 2009. By virtue of an English teaching gig in Hong Kong, I was fortunate enough to personally witness her observation that there are, in fact, a lot of Chinese people in the world. Anyone there that night, even those who didn’t speak English – and that was most people – noticed that the New York City showgirl was a strange bird; visually, her nonsensical wardrobe made her more Dada than Gaga. A string of pop hits and eclectic dance moves was forgettable, but it was Gaga’s grandeur, evident from a 100 rows back and three sections up, that made her memorable, enough, at least, for me to share her insightful remarks on the Chinese populace three years later.

A pleasurable byproduct of creative excellence is the sense of awe. We’re drawn towards technical prowess in the arts, and when an object or performance showcases exceptional talent and virtuosity we feel effusive admiration for the creator, like a child gawking in the window of a candy store. Think about gazing at the Sistine Chapel or listening to the New York Philharmonic perform a rendition of Beethoven’s Fifth. (For me, it’s the reprise in Les Misérables.) The late Denis Dutton said it best: “skills exercised by writers, carvers, dancers, potters, composers, painters, pianists, singers, etc. can cause jaws to drop, hair to stand up on the back of the neck, and eyes to flood with tears. The demonstration of skill is one of the most deeply moving and pleasurable aspects of art.” This was the case in Macau, where all those Chinese teenyboppers and me left Gaga’s performance awestruck.

Creativity is impossible without awe. The history of creative output is a history of one creator reconciling a gushy esteem he has for another creator. Examples are scattered throughout history. Dylan is famous for emulating Woody Guthrie for years before breaking through with original music. Shakespeare spent considering time imitating Marlow plays. Even entire movements are born out of the awe-inspiring: A Sex Pistols gig in June of 1976 in Manchester is said to have jump-started a generation of punk music, which, some might argue, changed music forever; Dylan’s performance at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 was a catalyst for folk music in the United States; the most famous example (contemporary at least) might be The Beatles performance at Shea Stadium in the same year.

A Darwinian might argue that the motivation to imitate eminent creators is an attempt to distinguish oneself, with either an object or performance, within a community. Perhaps. But most artists pursue their craft not for status – or to get the girls – but because doing so is intrinsically fulfilling. It would be difficult to imagine a high school band director or a private French horn teacher in it for universal praise and glory. It’s more likely that they do it to fulfill an inherent desire to improve their craft. Awe-inspiring objects and performances are important because they propel the passion of a creative. Creativity would die a quick death if we didn’t possess the natural tendency to admire eminent creators.

Little research on when and how art and human creation elicit awe exists. A 2003 paper by Dacher Keltner and Jonathan Haidt defines awe as perceived vastness (an event or object that overwhelms us) and a need for accommodation (an event or object that forces us to rethink our worldview) and argues that physical and metaphoric size (e.g., Michaelangelo’s David or a Greek Myth), magical and impossible events – as opposed to what’s ordinary – and novelty contribute to a sense of awe. Its ability to generate a sense of communalism also defines awe. This was true in Macau, but it’s more prominent at raves, where a good DJ suppresses “I” and encourages “we.” Haidt mentions a few more characteristics in his recent book, The Righteous Mind: “Awe acts like a kind of reset button: it makes people forget themselves and their petty concerns. Awe opens people to new possibilities, values, and directions in life. Awe is one of the emotions most closely linked… to collective love and collective joy.”

If we understand awe as the feeling of wonder and excitement mixed with disbelief, Nature is probably its most reliable source. The ocean and the Grand Canyon are sobering and inspiring, so are things like the Hubble Deep Field, a tropical island, waterfalls, rainbows and sunsets. Dutton argues that our appreciation of these vistas is part of a natural evolved appreciation for beauty in nature. The positive psychologist Martin Seligman believes that appreciating beauty in nature, the arts or athletics is an important aspect of human flourishing. There is at least a degree of truth to these assertions. But there’s no doubt that a willingness to be awestruck is a central ingredient for creative expression, whether it comes from the Sistine Chapel or Gaga.

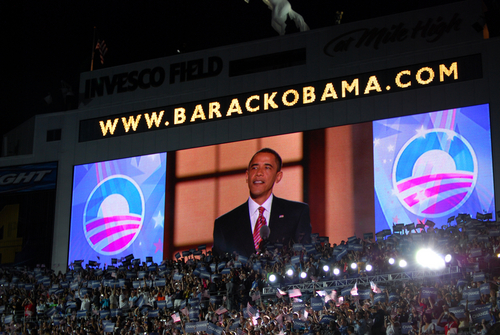

Image via Shuttershock/Matt Gibson