A Brief History of Outsider Science

If you look at the history of science you can ask have there been people who were outsiders in the past who are now accepted today. That raises an issue about what it means to be an insider or an outsider.

Until relatively recently – and it only dates back to the really the middle of the 19th century – science wasn’t a profession. So before it really became professionalized there were all sorts of people with competing ideas about what science could be or what science should be. So there were a lot of people in the 17th and 18th century who thought they were doing science and generally were trying to do science. They’re not names that we remember in the history books today because they’re strand of thinking isn’t what ultimately became mainstream. But in their own day there wasn’t really the question of insiders or outsiders because there wasn’t actually as it were a clearly defined cohort of insiders.

Science began to be professionalized in the mid-19th century and in fact, the word “scientist” dates to 1834. Before that the people we called scientists had called themselves natural philosophers and so the word scientist was really coined in 1834 to basically delineate this new group of people who were going to be professional scientists, which was meant to distinguish them from all of these gentlemen amateurs. So if you look back in history you can’t really talk about insider or outsider-ness before the mid-19th century. There were a lot of people doing a lot of different things before that and it wasn’t clear which ones of them would even be defined as science in the long run.

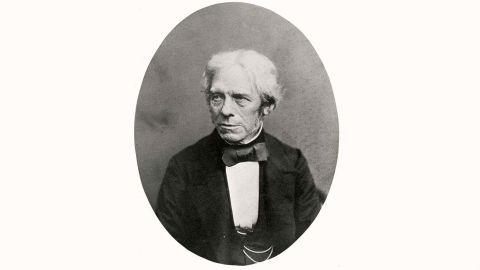

But since the mid-19th century has there been anybody who has had bizarre ideas that were not accepted in their own day, but are now? There actually is one great example of this and that’s Michael Faraday who was in many physicists’ eyes the greatest experimental physicist in history. He’s the guy who discovered the relationship between magnetic and electric fields. He discovered the mechanisms which became the electric motor and the electric generator. But Faraday in about the 1830s, 1840s put forward a radical idea. At the time everybody believed the universe was a mechanical system and Faraday said, “I believe that magnetism is actually propagating itself through this invisible field of influence.” And he said, “I believe electricity has this invisible field of influence and so does gravity.” That was a radical and heretical idea in the 1830s and 1840s and it didn’t get accepted in Faraday’s lifetime.

In fact, some of his biographers have claimed that Faraday died of a broken heart because this idea of an invisible field of influence was rejected as idiocy by his scientific peers who were all looking for concrete mechanical explanations. It wasn’t until really later in the century – the 1870s – that the idea of a field got accepted, and now we all accept this. Any school child can put iron filings on a piece of paper and move the magnet around and see the magnetic field and it seems like an obvious idea to us. But Faraday wasn’t accepted in his day.

In Their Own Words is recorded in Big Think’s studio.

Image courtesy of Shutterstock.