Approaching Normal

Nearly two decades ago, I walked into my first Abnormal Psychology class. Given the course title, I thought I had a pretty good handle on what the subject matter would be. So imagine my surprise when the professor walked in and said, “The ‘abnormal’ in the course title is a bit of a misnomer,” he stated. “Because when it comes to behavior, ‘normal’ is relative. In fact, there’s nothing to suggest that ‘normal’ is even the optimal when it comes to behavior.”

I cannot remember the professor’s name (though he did have a rather prolific beard). Nor can remember what year of college I took that class. But I remember him telling us about his doctoral work into the so-called “normal” family. “I quickly learned that the ‘normal’ family doesn’t exist,” he told us. “Tolstoy only had it half right. Every family, happy or unhappy, does it their own way. And that’s important to remember.”

As a teenager who had been trying hard to hide behind an appearance of “normal” all through high school–and then just gave up and decided that I might as well go in the other direction and strive for “abnormality”–this was quite a revelation. I wish someone had put it so plainly earlier in life.

Today, it feels like a bit of a given. Today’s teen is told to embrace their individuality, to appreciate that everyone is a little bit different. Yet, when you read about behavior, love, relationships, sexuality, brain activation–really, anything at all–it is always couched inside this old idea of “normal.” That there is only one healthy way of doing things. That while you can be an individual, you should do so within these rules, this weird interpretation of “normal.” Yet, we would do much better to remember that when scientists discuss “normal,” it is not a single phenomenon or a way of living, it’s a statistical representation.

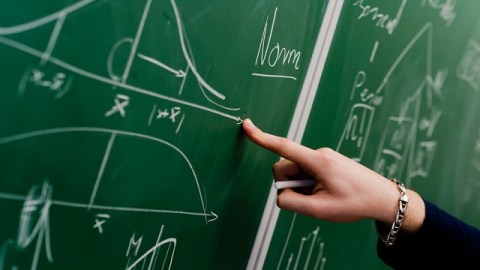

While many people may have tried very hard to forget statistics class, “normal” curves (often called bell curves) are a distribution of a variety of different data points. When scientists present their findings as a “normal” type of love, a “normal” sex life, a “normal” parenting style or even a “normal” family life, they are not giving us a single value or optimal way to behave. Rather, their discussions of “normal” usually represent a wide variety of behaviors distributed across the curve, with the more “normal” variations appearing at the curve’s apex and the rest fanning out to the sides. Even if you look at values only one standard variation away from the mean, you are generally looking at some fairly diverse values.

Politicians, pundits and blog trolls love to tell us what is “normal” — and these days, they are all too happy to pick and choose various scientific studies to back up their arguments. They want us to deny our biology and try to precariously climb up that curve, hanging on to the top with our fingernails at the expense of everything else. Of course, they leave out the fact that this “normal” standard is usually unattainable. And a dangerous way to apply science.

The truth about any complex behavior is that it is incredibly variable. The human brain’s complexity and plasticity mean that there is very little that is “normal” — at least in the way that most lay people explain it. And, frankly, human lives are more adaptable, more rich and more beautiful for it.

Credit: Oliver Sved/Shutterstock.com