Are “National” Artists a Thing of the Past?

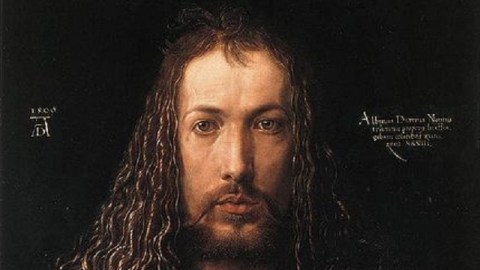

Say “nationalism,” and most minds immediately think “war.” Word association games aside, nationalism comes in all shapes and sizes, but the most dangerous form historically has led to armed conflict and borders shifting in blood. Embodiments of nationalist fervor always feel like the first symptoms of full-force nationalism. Are “national” artists a thing of the past? Or are they making a comeback? A major exhibition of the art of German artist Albrecht Dürer(whose Self-Portrait from 1500 appears above), whom many consider the “national” artist of Germany, raises the question of whether such a figure can exist in the 21st century and what it might mean if it could.

The Early Dürer opened on May 24th at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum Nuremberg amidst much excitement and controversy. Curators intended the show to illustrate new findings about Dürer’s early development. However, as the largest exhibition in 40 years since the grand 500th birthday party events held in 1971, The Early Dürer took on much larger implications. As Bernhard Schulz explained in a piece in The Art Newspaper, Munich’s Alte Pinakothek, the owner of the 1500 Self Portrait, lists the iconic painting as too valuable and too fragile to lend. When the portrait was lent to Nuremberg in 1971, a crack in the wood panel from an even earlier loan to Nuremberg in 1928 became worse. Travel restrictions on already damaged priceless paintings are common, but the commotion over this rejection was quite uncommon.

German politicians quickly became involved in trying to get the loan to happen. Even though the Alte Pinakothek lent two of their Dürers to the Nuremberg show and contend that no formal request was made for the 1500 Self Portrait, politicians painted the museum and Munich as trying to keep the “national” painter all to themselves. Fans of Nuremberg’s soccer (er, football) team waved banners at matches calling for the painting to come “home”—a sure sign, at least to me, of how far Dürermania spread beyond the idea of a simple art exhibition. In the end, the Self Portrait stayed put in Munich. Klaus Schrenk, director general of the Bavarian State Painting Collections, which includes that of the Alte Pinakothek, says in Schulz’s piece that, “If we had yielded to the pressure, it would have had an enormous effect. It would have meant that the treasures that lie in the museums, could be made available because of political concerns.” It’s those “political concerns” that seem most troublesome in this case.

Is Dürer really the “national” painter of Germany? Can any artists really stake a claim to such a title for any country? Who do you pick from Italy, for example? Leonardo? Michelangelo? Raphael? All of whom have legitimate claims, yet all of whom were less famous in their time than their northern contemporary Dürer, who even earned a mention in Vasari’s Lives among all those vowel-heavy Italian names. I sit here trying to pick a national painter of America and can’t finger a clear-cut number 1. And, yet, Dürer, even half a millennium later, continues to claim a central position in the collective German cultural consciousness. Perhaps there’s something unique about the German mindset. Perhaps Germany’s rising rank economically as the rest of Europe sinks deeper into a recession is making them want to couple that rise with renewed national pride in their cultural past. Anyone who knows anything about the saddest moments of 20th century history knows that Germany stood astride many of those moments, usually as a consequence of nationalist hubris. Maybe things will turn out better this time, but when even soccer fans start to care about museum loans, it’s hard not to worry that they won’t. I’m not predicting Germany starting a shooting World War III, but more modern forms of war—specifically economic—might be in the making.

[Image:Albrecht Dürer.Self-Portrait (detail), 1500.]