Are Some States of Living Worse Than Death? And Should Government Decide?

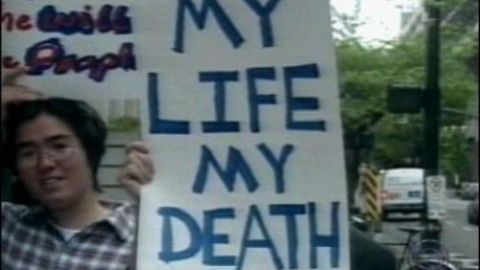

Strange name for a movement, isn’t it; “The Right to Die”? Isn’t that like asking the government for “The Right to Live” or “The Right to Eat” or “The Right to Think”? Strange, that we need to ask permission to end our own lives when we deem that our life is no longer worth living. Really strange, too, that the people who want government to deny this most basic personal choice include many who on other issues say government should be getting OUT of our lives, not into them as intrusively as this.

But this same question…whether there are conditions of living that make death preferable, and who decides…is hidden in something else government decides as well. In the process of comparing whether the benefits of some proposed life-saving policy outweigh the costs, analysts calculate the dollar Value of a Statistical Life (VSL. This is NOT a real specific person’s life, just a theoretical value of an average statistical life. There’s a great explanation of how VSL is calculated and used here.) They also calculate something called the QALY (kwAHly), or a Quality Adjusted Life Year, a sliding scale that rates not only how many years of life the policy will save but the quality of those years…how healthy people will be during those extra years of life. A QALY lived in perfect health rates a “1”, death gets a “0”, and various states of less-than-perfect health get some score in between.

As cold as it seems to say some years of life saved are worth more than others, let’s be honest. It also makes sense. After all, isn’t a policy that preserves years of life that can be lived in perfect health better than a policy that may save a lot of cumulative years of life across the population, but years that will be lived with some degree of disability?

The problem is, since the QALY scale only goes down to zero, and Zero = Dead, there is a value judgment in these numbers that gets us back to the Right To Die question; are there health states so bad that dying would be preferable? And who decides!?The surveys that set the value of a QALY ask the general public (yes, people like you and I determine this ranking) “How much you would be willing to pay for an extra year of life if you could live it in perfect health”, or “How much you would be willing to pay for an extra year of life if you were blind” or “bedridden” or “in pain”, or “if you had a terminal disease”, etc. But by setting Dead as the worst possible health state, the QALY game is rigged. Shouldn’t these surveys also ask us “How much would you be willing to pay to DIE if you were facing a terminal disease, or bedridden and irreversibly comatose, or in chronic excruciating pain, etc.” Shouldn’t the people who design these surveys also respect that, to some people, death is preferable to some awful ways of being alive? Should there be a QALY score below zero, a negative score for lives lived in such pain, or inescapable hopelessness, or so absent of any quality of life, that being dead is better!

Of course that is likely to offend religious conservatives just as much as does the idea of allowing people to take their own lives. Policy making that validates people’s beliefs that some forms of living are worse than death is a slippery slope to the same end. But we better face this issue, and not just with the obvious question about the Right to Die, because this question will only grow more urgent as the baby boomers age and move into their (our) final years. Millions of those ‘life years’ will be spent in fierce corrosive pain, or facing various inescapably fatal illnesses, or cut off from the outside world by profound cognitive limitations, or unconscious after strokes or heart attacks or just from the energy-sapping effects of the final part of aging (as was sadly recently the case with my father).

Many people find death preferable to living in such diminished circumstances. Society needs to resolve whether those personal beliefs supercede moral and religious beliefs that condemn suicide, and it needs to recognize that this same Right to Die question is hidden in how health policy is analyzed and chosen. In both areas, we have to resolve which values about this life or death question should prevail.