Are There ‘Laws’ in Social Science?

This post originally appeared in the Newton blog on RealClearScience. You can read the original here.

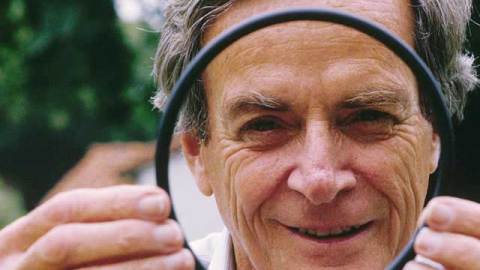

Richard Feynman rarely shied away from debate. When asked for his opinions, he gave them, honestly and openly. In 1981, he put forth this one:

“Social science is an example of a science which is not a science… They follow the forms… but they don’t get any laws.”

“They haven’t got anywhere yet,” Feynman furthered. But never one to rule out being wrong, he added with a grin, “Maybe someday they will.”

Many modern social scientists will certainly say they’ve gotten somewhere. They can point to the law of supply and demand or Zipf’s law for proof-at-first-glance — they have the word “law” in their title! The law of supply and demand, of course, states that the market price for a certain good will fluctuate based upon the quantity demanded by consumers and the quantity supplied by producers. Zipf’s law statistically models the frequency of words uttered in a given natural language.

But are social science “laws” really laws? A scientific law is “a statement based on repeated experimental observations that describes some aspect of the world. A scientific law always applies under the same conditions, and implies that there is a causal relationship involving its elements.” The natural and physical sciences are rife with laws. It is, for example, a law that non-linked genes assort independently, or that the total energy of an isolated system is conserved.

But what about the poster child of social science laws: supply and demand? Let’s take it apart. Does it imply a causal relationship? Yes, argues MIT professor Harold Kincaid.

“A demand or supply curve graphs how much individuals are willing to produce or buy at any given price. When there is a shift in price, that causes corresponding changes in the amount produced and purchased. A shift in the supply or demand curve is a second causal process – when it gets cheaper to produce some commodity, for example, the amount supplied for each given price may increase.”

Are there repeated experimental observations for it? Yes, again, says Kincaid (PDF).

“The observational evidence comes from many studies of diverse commodities – ranging from agricultural goods to education to managerial reputations – in different countries over the past 75 years. Changes in price, demand, and supply are followed over time. Study after study finds the proposed connections.”

Does supply and demand occur under the same conditions? That is difficult to discern. In the real world, unseen factors lurk behind every observation. Economists can do their best to control variables, but how can we know if the conditions are precisely identical?

Still, supply and demand holds up very well. Has Mr. Feynman been proved wrong? Perhaps. And if social science can produce laws, is it, too, a science? By Feynman’s definition, it seems so.

The reason why social science and its purveyors often gets such a bad rap has less to do with the rigor of their methods and more to do with the perplexity of their subject matter. Humanity and its cultural constructs are more enigmatic than much of the natural world. Even Feynman recognized this. “Social problems are very much harder than scientific ones,” he noted. Social science itself may be an enterprise doomed, not necessarily to fail, just to never fully succeed. Utilizing science to study something inherently unscientific is a tricky business.

(Image: The Feynman Series)