Can Artists Be Terrorists?

For countries such as Egypt facing life or death questions of freedom, art itself becomes a life or death proposition. Art can inspire, challenge, question, and even comfort, but can it terrorize? Egyptian street artist Ganzeer, along with Finnish street artist Sampsa and the German-based art collective Captain Borderline, have been labeled as terrorists by Egyptian media supportive of the policies of Abdul Fatah al-Sisi, the military leader behind the 2013 Egyptian coup d’état, interim leader of Egypt, and now the elected Egyptian president. Because of that terrorist label, Ganzeer’s been forced into hiding, although he and his cohorts refuse to be silenced in the battle of ideas culminating in the election (which Sisi won with 93% of a troublingly low voter turnout). This sad episode raises the question of whether any artist just by producing their art can be considered a terrorist.

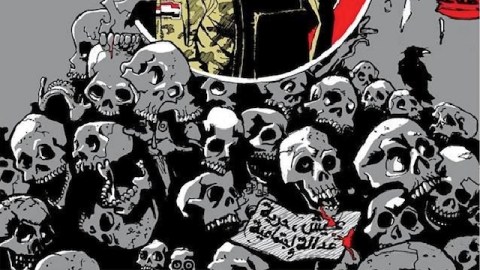

Western media became aware of this situation when Sampsa contacted the art news site Hyperallergic. Laura C. Mallonee’s article, “Two Street Artists and Artist Collective Labeled Terrorists in Egypt,” outlines the whole controversy, which began during the Cairo protests last year. As many commentators remarked, the protests in Egypt and throughout the Middle East relied heavily on social media. These artists relied on old-fashioned “social media” by creating street art critical of Sisi and the repression and violence by the establishment, including the removal of democratically elected President Mohamed Morsi. Ganzeer’s The Army Above All(detail shown above), which featured Sisi and other military figures atop a pile of civilian skulls, attracted international, Egyptian, and Sisi’s attention. (You can see a great example of the prevalence of Egyptian political street art in Tahrir Square last August here.) Street art as social media quickly became modern social media in the form of the #SisiWarCrimes hashtag campaign calling upon Sisi to respond to allegations of war crimes. Sisi then struck back through intermediaries such as television personality Osama Kamal, who claimed that these artists were in league with the Muslim Brotherhood (who were also critical of Sisi, but for different reasons) on his show Al Raees Wel Nas (in English, “The President and The People”) on May 9, 2014. Major Egyptian newspapers Youm 7 and Al Gomhuria repeated Kamal’s claim. Youm 7 is privately owned, but Al Gomhuria is run by the state, making the connection between the accusations and Sisi plain. Because an Egyptian court sentenced hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood members to death last April, the accusations amount to a death sentence.

Ganzeer responded to Osama Kamal and cohorts with a blog post titled “Who’s Afraid of Art?” (The answer, apparently, is Sisi.) “Such ridiculous accusations could very easily get that someone killed,” Ganzeer writes. “Does Mr. Osama really want to see me hang for my art? Perhaps Mr. Osama merely wants to send a little scare down my spine so I can alter my positioning?” However, Ganzeer stands up to Sisi and friends where others have laid down: “Well, Mr. Osama, if you’ve ever known an artist in your life, you would know that the only thing artists respond to is their conscience. Unlike journalists who may fear losing their jobs, or NGOs [non-government organizations] who may fear getting shut down, or political parties who may fear being banned from activity… I, Mr. Osama, only fear making art that is irrelevant. Your statements about me, however, have only proven the significance of my work. Nice going.” In other words, if a humble street artist can get labeled as a terrorist by someone such as Sisi, he must be doing something right. Ganzeer sees a clear progression in Sisi’s silencing of opposition from the NGOs, the Muslim Brotherhood, the youth movement, non-compliant journalists, and now, at the bottom of the food chain, street artists. “The methodology of doing so first involved massive defamation campaigns throughout Egyptian media, followed by brutal crackdowns cheered by media-zombified masses,” Ganzeer writes in explaining Sisi’s pattern of oppression. “And now as the only remaining unrestricted voice on the scene, Egyptian street-artists are the State’s next target.”

As in proper journalism, socially conscious art should, in the immortal words of Finley Peter Dunne, “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” Ganzeer in an American context would be a modern-day Ben Shahn. But would Ben Shahn be considered a terrorist today? I’ve been wracking my brains for candidates for terrorists in art history. Iconoclasts of all stripes and time periods sharing the common goal of destroying art expressing beliefs they disagree with and replacing it with more “acceptable” art certainly fit the bill. Alfred Jarry, whose actions and pseudoscience of ‘pataphysics later inspired the softer terrorism of the Surrealist and Futurist movements, allegedly fired his revolver indiscriminately as a kind of performance art, which would make him an excellent art terrorist candidate. Pablo Picasso, who found Jarry fascinating enough to buy Jarry’s revolver after the pataphysician’s death to wear on nighttime excursions in the City of Light, almost became an art terrorist himself in a fine bit of ethnic profiling when the French authorities suspected the odd Spaniard who suspiciously frequented the Louvre of stealing the Mona Lisa. Dada aspired to art terrorism with their special brand of anti-tradition and anti-culture, but they seemed more like an elaborate, playful game than a serious enterprise.

Terrorism, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. To Sisi, Ganzeer and these street artists may seem like terrorists, while they, in turn, clearly see Sisi as the real terrorist. Then there’s the issue of how do you define “terrorism”: is it the wielding of ideas as weapons or is it actual bombs and military weapons turned on defenseless people? Unlike Sisi, these street artists haven’t hurt anyone. Few artists do. When Woody Guthrie wrote “This Machine Kills Fascists” on his guitar, he didn’t mean it literally. In his email to Hyperallergic, Sampsa asked, “If we are not terrorists—which is clear—as the only thing we have done is paint against the general—then who else is not a terrorist?” Once someone starts labeling artists (or anyone peacefully demonstrating against those in power) as terrorists with the aim of silencing, if not killing them, the word itself loses meaning everywhere. Unfortunately, Sisi will go on, but fortunately these artists have pledged to go on as well despite the dangers. In the end, the real fear is the idea that the real terrorists are those crying “terrorist” for their own purposes and not for the public good.

[Image:Ganzeer. The Army Above All(detail), 2013. Image source.]