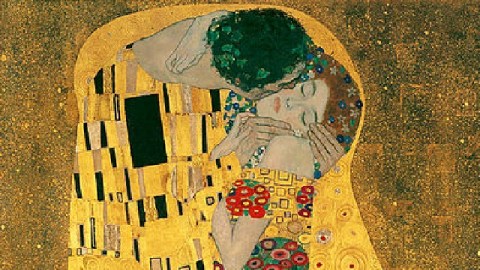

Gustav Klimt—Genuine Genius or Overhyped Kitsch?

You know you’ve made the big time when you rate a Google Doodle, as Gustav Klimt did this past weekend in recognition of the 150th anniversary of his birth. Anyone around the world Googling for knowledge got a glimpse of Klimt’s iconic 1907 painting The Kiss (detail shown above). For many people, however, Klimt’s almost as overused and overexposed as Google itself. The Valentine’s Day-ification of The Kiss seems to have smoothed the rough edges of the bad boy of turn of the 20th century Vienna and made him more kitsch than kunst. When the centennials and sesquicentennials roll around, reevaluations become unavoidable. So, can we say for certain whether Klimt’s genuine genius or overhyped kitsch?

Klimt definitely wowed the crowds of his day. Working bold and often big, Klimt captured the imagination of his Austrian audience. A fin de siècle sex symbol, Klimt painted nude bodies that thrilled viewers enjoying the loosened sexual mores of the period. Rumors spread that Klimt kept nude models scattered about his studio for impromptu inspiration (and stimulation). Society ladies flocked to have him paint their portrait and to have real, or merely rumored, affairs. Then, as now, and as always—sex sold. Working gold leaf into works such as The Kiss, Klimt seemed to have a golden touch that stirred the passions of the people—either for or against him.

And, yet, hearing the name “Klimt” sometimes fills me with dread, not at the prospect of seeing his paintings, but at all the hype that sometimes surrounds them. Adele Bloch-Bauer I, the “Golden Girl” of the Neue Galerie in New York City and probably the finest Klimt in America, sold for a then-record $135 million in 2006—an obscene amount for any one painting and more a grand gesture of collecting than a true valuation of the work itself. I loved seeing the painting at the Neue Galerie when it first came there, but the filthy lucre linked to the portrait, which already had a long, sad history of theft and restitution, tarnished my appreciation somewhat. Klimt’s also victim to the second worst film ever made about a major artist. Beaten out only by Andy Garcia’s 2004 film Modigliani, John Malkovich’s 2006 misportrayal of the title character in Klimt plays up every sensationalist, sexual angle. The result makes Eyes Wide Shut seem restrained and almost coherent by comparison. That Klimt is the king of kitsch. The Wien Museum even ran a contest (and set up a Facebook gallery) asking people to submit their favorite Klimt kitschy item. Their “favorites,” but not mine. I say that as someone with Rodin MuseumThinkerANDDa Vinci’s Last Supper snow globes, so I appreciate kitsch. But Klimt kitsch makes me cringe.

The Klimt I love goes deeper than just a superficial kiss. Most people see only the detail I give above—the kiss itself—or marvel at the decorative cloak that envelops the pair. Few notice that the woman isn’t kissing back, or that her feet hang perilously over the edge of a cliff. (The Belvedere in Vienna, which owns The Kiss, hosts a huge Masterpieces in Focus: 150 years of Gustav Klimt until January 6, 2013.) The Klimt I love painted monumental public works such as the Beethoven Frieze (which I’ve only seen in books and once in full-scale reproduction, but which visitors to the Vienna Secession Building can see closer than ever thanks to a new platform system) and allegorical ceiling paintings at the University of Vienna (which exist only in photographs today thanks to the Nazis scorched earth policy at they retreated at the end of World War II). The Klimt I love knew eros, of course, but also thanatos, and knew how to merge the two in works such as Hope II, in which a pregnant woman looks down at her swelling belly upon which a skull sits. There’s no greater love than that of a mother for her child, but even that exists in the shadow of death, hence the “hope” of the title. No snow globe can contain such a sentiment.

Alas, for Americans, the Neue Galerie’s the sole place to get your Klimt on, thanks to their celebration through August 27th. Austria considers Klimt a national treasure, making loans rare and sales nearly impossible. (Adele Bloch-Bauer I could move because of the restitution loophole.) If you want to see the real Klimt, the Klimt I love, you’ll have to go to Vienna in 2012. They’ve even set up a website to list all the Klimt tributes, complete with a contest called “Klimt Yourself” (ending July 17th), with the prize a chance to visit Vienna. The real prize will be getting to know the real, and not the hyped, Klimt.