Is Print the New Counterculture?

Since March of this year, a series of extraordinary paper sculptures has appeared in various locations around Edinburgh, Scotland. Each location is a library or other institution devoted to the preservation of the arts; each sculpture is accompanied by a handwritten note celebrating that same cause. “We know that a library is so much more than a building full of books,” reads one. “This is for you in support of libraries, books, words, ideas…”

The artist has apparently wrapped up the project, but her identity remains unknown. She has identified herself as female, has thanked a photographer colleague by name, and is clearly a fan of mystery novelist Ian Rankin, whose books several of her sculptures incorporate or allude to. Otherwise, she’s left no clues about herself. She’s an anonymous folk artist (folk hero?), a Banksy of the bookshelves.

The print fetishism evident in her works—her loving use of clippings from faded-looking volumes, her defiant insistence on the worth of pre-digital culture—has me wondering whether print is acquiring a new identity. Twenty years ago the Web was a brand-new medium; ten years ago it was still an underdog. Its users were disproportionately young and male, and its prominent entrepreneurs, such as Larry Page and Sergey Brin, were considered scrappy revolutionaries. Now the Web is the establishment. Even TV and film are yielding to its primacy. As Google, Facebook, and Amazon conquer the planet, it seems just possible that print could become the haven of a new counterculture.

Stop laughing, you square.

Granted, digital media are now so integral to the way the world functions that even the most contrarian hipster will never shun them entirely. And some digital juggernauts—Apple, for example—retain a certain chic, even a rebel aura, among younger consumers. But popular sentiment toward Silicon Valley is shifting. You can see it in the portrayal of Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network or in the latest scathing Gawker piece about Google. You can feel it in the swift backlash against Steve Jobs hagiography in the wake of his death. The Web elite are now our power elite, less beloved than envied and distrusted. More importantly, the Web is becoming the limelight and other media the shadows. These days, if you want to bow out of the mainstream, you go offline, not on.

For activist rebels, that shift could make print tactically advantageous. Digital media have become the overwhelming focus of state and corporate surveillance; witness, for example, the reported police monitoring of Occupy Chicago protestors’ cellphones. An underground print publication in today’s climate would arguably be more underground than ever. (That is, like an equivalent website in the ‘90s, it wouldn’t be invisible but it might go unnoticed.)

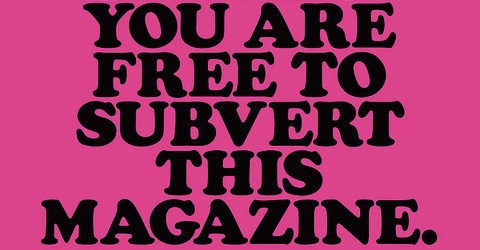

For rebels in the creative realm, meanwhile, print offers both nostalgic appeal and a branding angle. Also, of course, a medium that’s lush and tangible and durable. In recent years that medium has been ardently championed by prominent younger authors, through public encomia (e.g., Dave Eggers on behalf of McSweeney’s) and lavish formal experiments (e.g., Jonathan Safran Foer in Tree of Codes). I think we’ll see other writers follow their lead, and perhaps even witness a flowering of journals like the recently launched Explosion-Proof, whose credo reads as follows:

Explosion-Proof is not a blog, as we hate blogs. It is not an internet magazine, as we don’t believe the screen is the best home for the serious rumination that good writing demands. Yes, you are reading this on the internet. No, you will not find much content on this site. We are aware of the shortcomings of dead-tree publishing. It will be expensive. It will limit our readership. We remind those who feel these are two insurmountable obstacles that books, the kind held in hand and laid on shelves, may not travel the speed of light, but neither do they disappear when plugs are pulled. And, we guarantee, neither do they explode.

As a despised blogger I’d venture that the first part of this goes too far, but as a believer in literary immortality I like the second.

It’s easy to imagine the Phantom Paper Sculptor sympathizing, too. Her brand of subversiveness is more whimsical than angry, but like all good underground artists she seems to harness an energy in the cultural atmosphere. With canny symbolism, one of her pieces depicts a T-rex bursting from the pages of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World. Print will never again rule the planet, but the old dinosaur could still come back with a vengeance.

[Image courtesy Flickr Creative Commons, user TCOLondon.]