Study: Black and White Frame Spurs Black-and-White Judgments

Trial lawyers who advise male defendants to dress in dark suits and white shirts might think twice about that notion after a look at this study, soon to appear in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. The experimenters found that people asked to weigh moral dilemmas that were printed in a black-and-white frame made more extreme, “black-and-white” judgments than did people who read the same material in a different setting.

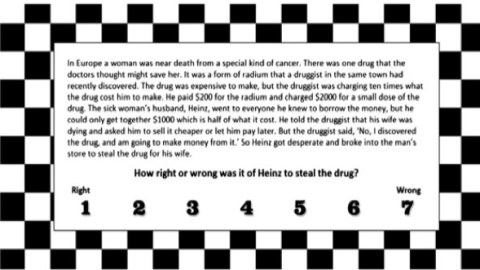

The authors, Theodora Zarkadi and Simone Schnall, offered people a much-used test of moral reactions. It’s the story of Heinz, who can’t afford his wife’s cancer medication. He ends up stealing the drug, and people are asked to evaluate whether his act was right or wrong, on a scale from 1 to 7 (1=totally right, 7=utterly wrong). In the Zarkadi-Schnall version (which 111 people took via a website), the paragraph appeared to some in a black and white checked frame (there’s a pic next to my headline). Others saw a plain gray frame. And a third group saw a different set of checks—blue and gold. (This was designed to separate the effect of any color scheme from the effects of black and white in particular.)

Zarkadi and Schnall then ran the statistics to see if there was any relationship between the extremity of people’s responses and the way they had seen the story. They weren’t interested in whether people were more extremely supportive of Heinz or against him; what mattered was how intensely they felt. On the 1-7 scale, a middling judgment is a 4. So the authors tabulated how far each group went, on average, from that midpoint.

Results: The group that had seen the question in a checkered frame gave judgments that deviated more from the center. Those people tended more to extremes than did the group that saw a neutral background or those who saw brightly-colored checks. A follow up experiment, in which volunteers rated their moral view of pornography, adultery, drug use, littering, smoking and profanity, showed a similar significant difference between those who saw black-and-white framing and those who didn’t—for smoking, drugs and adultery. (As you might expect, feelings weren’t so extreme about littering, swearing and porn.)

It’s a bedrock assumption in courts, workplaces, schools and other modern institutions that people, when they must, can pull up their socks and make decisions based on evidence and the application of rules—and that they can “show their work,” explaining just why they decided as they did. A wide range of researchers have been chipping away at this bedrock now for some time. In labs, they’ve found that their experimental subjects made riskier decisions when hungry; and that people who have had a chance to wash their hands are more tolerant of deviance (another study of Schnall’s). Meanwhile, retrospective studies of actual behavior in real institutions have found that medical school interviewers judge candidates more severely when it’s raining and that parole board reviewers are harsher on cases that come at the end of a stretch of work than they are when they’re fresh. These studies, though, at least imply that some kind of emotion was involved when circumstances altered people’s decisions. Hunger and fatigue are stressors, the sense of cleanliness is agreeable, and rain tends to bum people out.

In these new experiments, though, the trigger was a mere perception: A black and white setting, the authors say, was enough to prime people to black and white judging.

Follow me on Twitter: @davidberreby

Zarkadi, T., & Schnall, S. (2012). “Black and White” Thinking: Visual Contrast Polarizes Moral Judgment Journal of Experimental Social Psychology DOI: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.11.012