The Most Challenging Exploration on Earth

Four days ago the hybrid remote controlled vehicle Nereus began its 40-day mission to explore the Kermadec Trench, one of the deepest oceanic regions on the planet. Diving below 6,000 meters for extended periods of time has long challenged humanity. Nereus will descend further than Mount Everest rises, surpassing 10,000 meters with a rugged body that can handle 15,000 pounds of pressure per square inch.

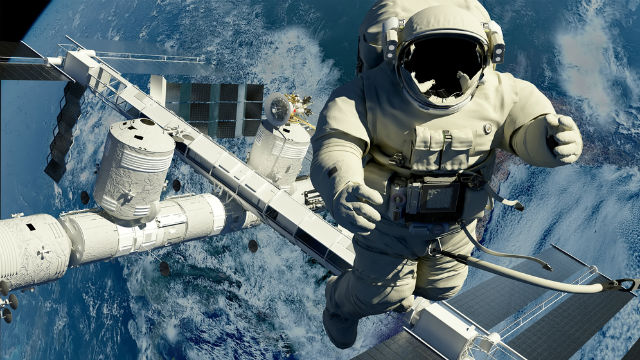

Part of the aptly named HADES mission (Hadal Ecosystem Studies), Nereus represents a needed advancement in our underwater exploration capabilities. Our space agencies currently have satellites orbiting on or around all major planets in our system, yet diving has long baffled us.

Before director and explorer James Cameron touched down in the Mariana Trench in March, 2012, no human being had ever seen, with his own eyes, such depths. The Avatar director plunged nearly 11,000 meters, donating the findings and vessel to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, the same institution that launched Nereus this week.

Researchers are hoping to uncover life forms previously unknown to us (which could lead to medical discoveries), better understand how tsunamis operate and piece together secrets regarding the origins of life on this planet. While a lot of recent scientific focus has been on our expanding comprehension of the universe, deep sea exploration is another equally riveting field in its infant stages. As Cameron said,

We’ve barely scratched the bottom. We’ve thrown just a handful of darts at the board.

Despite incredible technological advances, there remains one place that might be the most challenging to explore. In the latest issue of Shambhala Sun, Buddhist teacher Judy Lief writes that we often relate to our spiritual practice as an exercise form: fitness is more relevant than clarity and insight.

We tend to like spiritual practices that are not too threatening, practices that confirm what we are doing and help us do it better. Instead of looking into our fundamental being, we prefer to relate meditation as a self-improvement exercise.

The problem, she continues, is that you are then using a discipline to back up what you want to be true instead of as a tool of self-investigation that might require facing what really frightens you—in this case, distractions.

Being distracted is nothing new. While today we talk about our attention being diverted by an onslaught of social media, the fact that our minds are constantly turning to other topics did not emerge with the internet. Buddhists call this ‘monkey mind,’ a brain ceaselessly churning out thoughts while never resting on one for an extended period of time.

The issue, as Lief and others discuss in the magazine, is that if distractions are never addressed, contentment is impossible. It’s similar to when you first begin to meditate. You sit down, close your eyes, fascinated by the relentless nature of thoughts. Yet thoughts do not just happen to emerge only during meditation; this is what your brain is always doing. By addressing the matter by consciously attempting to slow the assault you’re noticing it for the first time.

Our brains produce thoughts—that’s what it does (among many other things)—thousands and thousands of them per day. Think about the last time you weren’t thinking about something. Unless you were meditating, when thoughts don’t actually cease but you are able to focus more clearly on one subject, there is never a time when your head is not filled with something: dinner plans, going to bed, that comment you should not have made yesterday.

Meditation is the process of self-investigation, the brain investigating itself. When you first begin to do so, it seems completely irrelevant. Why am I sitting here not doing anything? What is the purpose of doing nothing? My legs ache. My head hurts. And so forth.

The problem with such an approach is that meditation is not doing ‘nothing.’ It might be the most challenging exploration possible. A mind that is able to clearly see itself free of distractions—well, observing distractions without being taken by them—is one that can regulate its own thoughts and emotions. This does not mean the ravages of our inner world ceases; it does, however, give us a sense of control that helps us make better informed decisions.

As neuroscientist and author Sam Harris writes about meditation,

The trick is to become sensitive to what consciousness is like the instant you try to turn it upon itself. In that first instant, there’s a gap between thoughts that can grow wider and become more salient. The more it opens, the more you can notice the character of consciousness prior to thought.

It is that character we are searching for. Who are you before being distracted by the tireless barrage of mental imagery? In an age when we are collectively reaching further out and further down than ever before, the art of reaching in remains the most challenging and mysterious—and potentially rewarding—facet of our existence.

Image: C.K.Ma/shutterstock.com