Walt Whitman, Frankenstein, Dracula, and the Afterlife

The smallest sprout shows there is really no death,

And if ever there was it led forward life, and does not wait at the end to arrest it,

And ceas’d the moment life appear’d.

All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses,

And to die is different from what anyone supposed, and luckier.

[“Song of Myself,” section 6]

Walt Whitman always wrote with great authority, even eagerness, about death. “Sane and sacred,” he calls it in “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d,” his great elegy for President Lincoln. In “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking” he imagines the sea whispering the “low and delicious word” to him: “Death, death, death, death, death.” And in the passage above he teases us with an afterlife at once more natural and more mysterious than anything yet conceived.

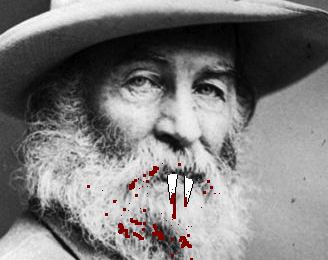

But for all his prophesying, how could he—how could anyone—have foreseen the weirdness of his own afterlife? Who knew that Walt Whitman would one day become Dracula, and narrowly miss becoming Frankenstein’s monster?

I am brooding on these things after reading Cynthia Haven’s recent Book Haven article on “Frankenstein and Walt Whitman’s Brain.” In it, she argues ingeniously that—“though it cannot be proved for certain”—an actual incident inspired the scene in the 1931 Frankenstein film in which a lab assistant drops a jarful of brains. That incident involved the brains of America’s greatest poet, who had donated his remains to the “science” of phrenology:

You see, Walt Whitman’s postmortem brain was put into some sort of a jam jar, and somebody dropped it, and it shattered. The brain, not the jar … or rather, probably, both. Or neither. Actually, it’s not certain the brain ever made it into a jar, or was dropped while it was in a sort of rubber sack.

One thing is clear, according to her historical source: “The records state quite definitely that the brain was accidentally broken to bits during the pickling process.” Well, Whitman did warn us in the closing lines of “Song of Myself”: “If you want me again look for me under your bootsoles.”

Granted, this anecdote makes him only a tenuous footnote to the Frankenstein legend. After all, it’s the dropped brains that fail to make it into the skull of the monster. But the connection becomes eerie in light of his much stronger claim to being Dracula. Dennis R. Perry explored this matter in depth in a 1986 Virginia Quarterly Review article, noting the “striking” physical similarities between Whitman and the vampire of Bram Stoker’s novel: “Both have long white hair, a heavy moustache…and a leonine bearing.” Perry finds an equally striking parallel between an image from “Song of Myself” and an image from Dracula, both involving a mouth pressed erotically to a man’s breast. (In only one case does the scene involve blood.) Then there is the “rhythm, parallelism, and balance” of Dracula’s speech, which Perry argues is recognizably Whitmanian.

It turns out Stoker may have had a bit of a crush on Whitman, though whether this went beyond literary hero-worship is anyone’s guess. In college he wrote Whitman letters in which he describes having “felt [my] heart leap toward you across the Atlantic and [my] soul swelling at the words or rather the thoughts” of the poems. He referred to Whitman as “Master” and performed little favors on the poet’s behalf, even arranging for his bust to be sculpted. He traveled to meet his hero several times during his life, and began work on Dracula three years after their last meeting (two before Whitman’s death).

Of course, this is all circumstantial evidence. But once you start reading Whitman into Dracula, it becomes hard not to read Dracula back into Whitman. Maybe it took an imagination as bizarre as Stoker’s to see it, but the Good Gray Poet of Brooklyn has a remarkably vampiric streak. It isn’t just his fascination with death, coffins, and the grave; it’s his obsession with lingering after death, with moving unseen among the living:

Closer yet I approach you;

What thought you have of me, I had as much of you—I laid in my stores in advance;

I consider’d long and seriously of you before you were born.

Who was to know what should come home to me?

Who knows but I am enjoying this?

Who knows but I am as good as looking at you now, for all you cannot see me?

[“Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”]

Or lingering after nightfall, moving unseen among the sleeping:

I wander all night in my vision,

Stepping with light feet, swiftly and noiselessly stepping and stopping,

Bending with open eyes over the shut eyes of sleepers,

Wandering and confused, lost to myself, ill-assorted, contradictory,

Pausing, gazing, bending, and stopping.

[“The Sleepers”]

In “Song of Myself” he commands his audience:

Undrape! you are not guilty to me, nor stale nor discarded,

I see through the broadcloth and gingham whether or no,

And am around, tenacious, acquisitive, tireless, and cannot be shaken away.

He wants you to envision him as a guardian spirit, but just as often ends up sounding like something with its fangs plunged in your neck.

So the strange cosmic career of Walt Whitman continues. He is large, he contains multitudes, and those multitudes turn out to contain monsters. Would he have rejected his posthumous roles in horror films, his accidental influence on Trueblood and the Twilight books? No, he would have relished them. (Who knows, may be relishing them yet.) The man who claimed to have been cared for by dinosaurs before his birth (“Song of Myself,” section 44); who declared himself the equal of Jehovah and Allah and all the other gods (section 41); who believed most profoundly that he was what Carl Sagan called “star stuff,” his body of a piece with the universe and everything in it—this man, who expected everything out of death, and nothing but the unexpected, would hardly have batted an eyelash at turning into Dracula.