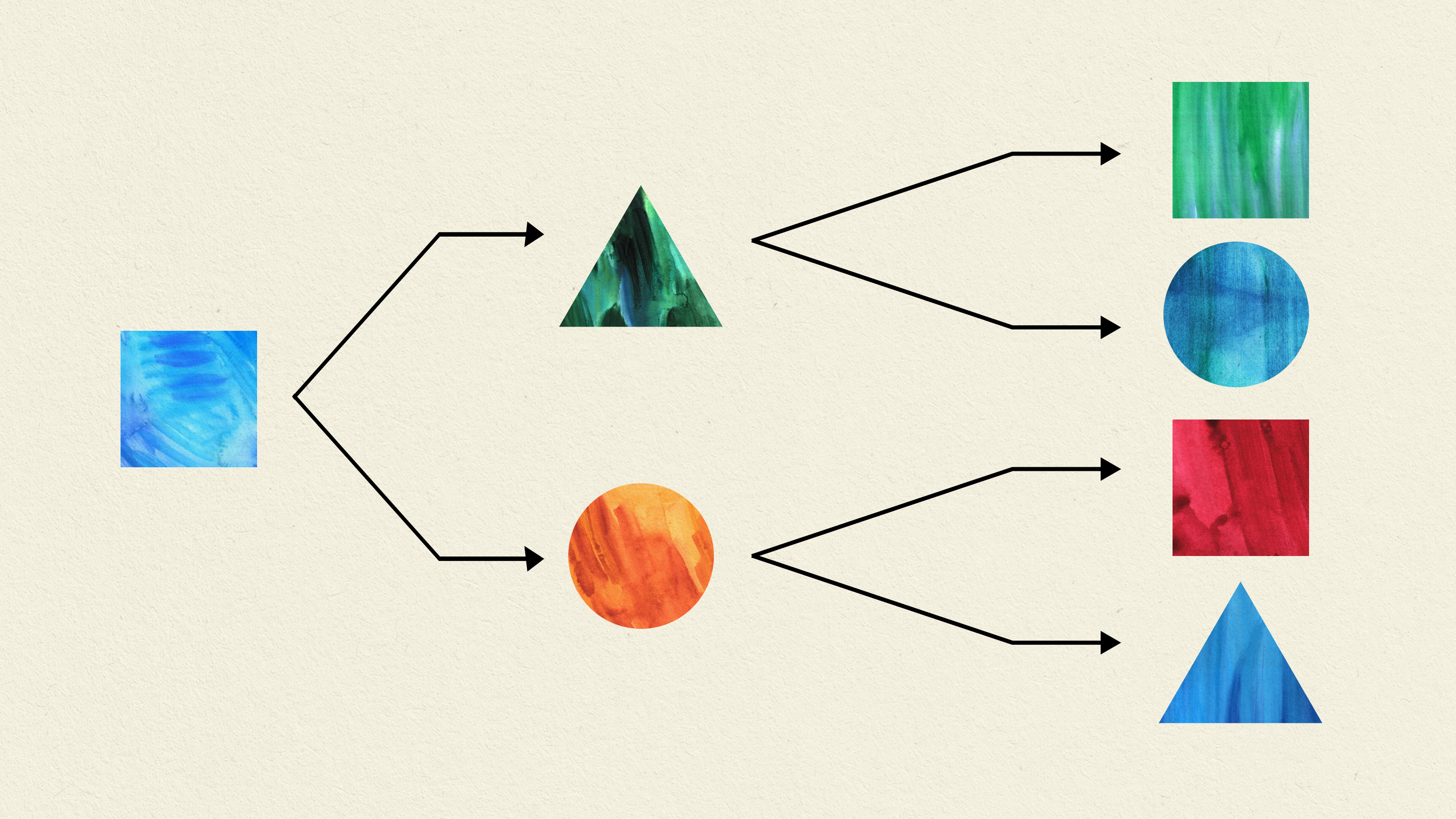

2 key principles are followed by the best decision-makers

- People too often end up solving the wrong problem.

- The first lens into any issue rarely reveals what the real problem is — and teams of smart, type A people tend to move into “solution mode” too quickly.

- The way we define a problem shapes everyone’s perspective about it and determines the solutions.

The first principle of decision-making is that the decider needs to define the problem. If you’re not the one making the decision, you can suggest the problem that needs to be solved, but you don’t get to define it. Only the person responsible for the outcome does. The decision-maker can take input from anywhere — bosses, subordinates, colleagues, experts, etc. However, the responsibility to get to the bottom of the problem — to sort fact from opinion and determine what’s really happening — rests with them.

Defining the problem starts with identifying two things: (1) what you want to achieve, and (2) what obstacles stand in the way of getting it.

Unfortunately, people too often end up solving the wrong problem. Perhaps you can relate to this scenario, which I’ve seen thousands of times over the years. A decision-maker assembles a diverse team to solve a critical and time-sensitive problem. There are ten people in the room all giving input about what’s happening — each from a different perspective. Within a few minutes someone announces what they think the problem is, the room goes silent for a microsecond… and then everyone starts discussing possible solutions.

Often the first plausible description of the situation defines the problem that the team will try to solve. Once the group comes up with a solution, the decision-maker feels good. That person then allocates resources toward the idea and expects the problem to be solved. But it isn’t. Because the first lens into an issue rarely reveals what the real problem is, so the real problem doesn’t get solved.

What’s happening here?

The social default prompts us to accept the first definition people agree on and move forward. Once someone states a problem, the team shifts into “solution” mode without considering whether the problem has even been correctly defined. This is what happens when you put a bunch of smart, type A people together and tell them to solve a problem. Most of the time, they end up missing the real problem and merely addressing a symptom of it. They react without reasoning.

The social default… encourages us to react instead of reason, in order to prove we’re adding value.

Many of us have been taught that solving problems is how we add value. In school, teachers give us problems to solve, and at work our bosses do the same. We’ve been taught our whole lives to solve problems. But when it comes to defining problems, we have less experience. Things are often uncertain. We seldom have all the information. Sometimes, there are competing ideas about what the problem is, competing proposals to solve it, and then lots of interpersonal friction. So we’re much less comfortable defining problems than solving them, and the social default uses that discomfort. It encourages us to react instead of reason, in order to prove we’re adding value. Just solve a problem — any problem!

The result: organizations and individuals waste a lot of time solving the wrong problems. It’s so much easier to treat the symptoms than find the underlying disease, to put out fires rather than prevent them, or simply punt things into the future. The problem with this approach is that the fires never burn out, they flare up repeatedly. And when you punt something into the future, the future eventually arrives. We’re busier than ever at work, but most of the time what we’re busy doing is putting out fires — fires that started with a poor initial decision made years earlier, which should’ve been prevented in the first place.

And because there are so many fires and so many demands on our time, we tend to focus on just putting out the flames. Yet as any experienced camper knows, putting out flames doesn’t put out the fire. Since all our time is spent running around and putting out the flames, we have no time to think about today’s problems, which can create the kindling for tomorrow’s fires.

We’re busier than ever at work, but most of the time what we’re busy doing is putting out fires — fires that started with a poor initial decision.

The best decision-makers know that the way we define a problem shapes everyone’s perspective about it and determines the solutions. The most critical step in any decision-making process is to get the problem right. This part of the process offers invaluable insight. Since you can’t solve a problem you don’t understand, defining the problem is a chance to take in lots of relevant information. Only by talking to the experts, seeking the opinions of others, hearing their different perspectives, and sorting out what’s real from what’s not can the decision-maker understand the real problem.

When you really understand a problem, the solution seems obvious. These two principles follow the example of the best decision-makers:

- The Definition Principle: Take responsibility for defining the problem. Don’t let someone define it for you. Do the work to understand it. Don’t use jargon to describe or explain it.

- The Root Cause Principle: Identify the root cause of the problem. Don’t be content with simply treating its symptoms.

I once took over a department where the software would regularly freeze. Solving the problem required physically rebooting the server. (The drawback of working in a top-secret facility was our lack of connectivity to the outside world.)

Almost every weekend, one of the people on my team would be called into work to fix the problem. Without fail, he’d have the system back up and running quickly. The outage was small, the impact minimal. Problem solved. Or was it?

At the end of the first month, I received the overtime bill to sign. Those weekend visits were costing a small fortune. We were addressing the symptom without solving the problem. Fixing the real problem required a few weeks of work, instead of a few minutes on the weekend. No one wanted to solve the real problem because it was painful. So we just kept putting out flames and letting the fire reignite.

A handy tool for identifying the root cause of a problem is to ask yourself, “What would have to be true for this problem not to exist in the first place?”