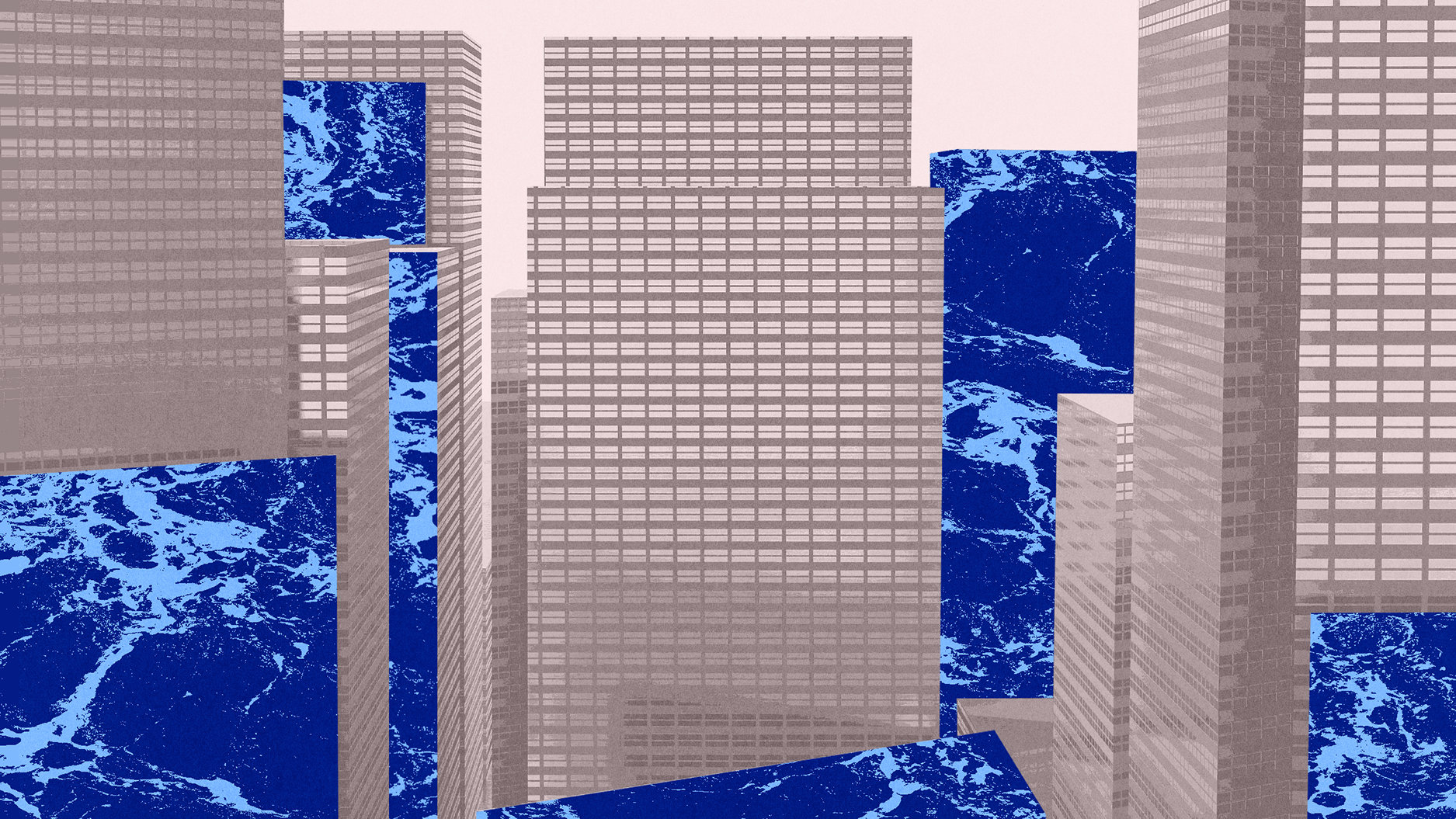

Fair bosses: The true “Empire State of Mind”

Credit: Creative Commons CC0

- Hot meals and double pay for construction workers were behind the success of the Empire State Building, constructed in just 13 months in the 1930s.

- According to a study by the London Business School, companies that treat their staff well tend to outperform the stock market.

- If a job requires creativity, any attempt to turn workers into automatons will be fruitless.

Perhaps the template for the tough manager dates back to the early days of the industrial revolution. The first factory workers had spent their lives working either as artisans or farm workers, where they had some control over either the hours or the pace at which they worked. Factory owners had invested a lot of money in machinery and they wanted to get the maximum return. As a result, they insisted on strict discipline. Indeed, many factory owners preferred to hire women, or children, who were easier to control.

The harsh rule of managers (and their agent, the factory foreman) explains why workers decided to form trade unions so they could fight to get better pay and working conditions. One industry that was plagued by industrial disputes was car manufacturing, and the result was often poor quality cars produced at high prices. Consumers had to put up with the situation because the industry was dominated by a few producers, such as General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler in the US or British Leyland in the UK. But in the 1970s, strong competition emerged in the form of the Japanese producers which initially focused on smaller, cheaper vehicles. The pioneer was Toyota, which had developed a “lean manufacturing system” designed to reduce waste and eliminate faults. A key element was a concept called jidoka, which means “automation with a human touch.” Any workers could stop the production line to prevent a fault. This required management to trust the workers to make responsible decisions, and implied a much more collaborative approach than the Western system.

More generally, treating employees well seems to work. Alex Edmans of the London Business School conducted a study looking at those businesses ranked the “100 best companies to work for” published by Fortune magazine. The data (compiled by the Great Place to Work Institute) cover the period 1984 to 2011. After controlling for factors such as size and industry sector, the businesses that treated their staff well produced stock-market outperformance of 2.3–3.8% a year, a substantial cumulative gain.

In his book The Art of Fairness, David Bodanis recounts a number of tales about managers who have had striking success by treating their workers with fairness and empathy. One of the most striking examples is the Empire State Building, which was built in just 13 months in the 1930s, a period which also included the dismantling of the hotel that originally occupied the site. Paul Starratt, the builder, paid his workers double the daily rate and devoted a lot of attention to safety, paying the employees in full on days when it was too windy to operate. Hot meals were delivered to the workers, even on the higher floors. The project had very low staff turnover and workers even suggested productivity improvements.

Another example cited by Mr Bodanis was from the public sector; the 2012 London Olympics opening ceremony organised by Danny Boyle, the film director. Thousands of volunteers were needed for the ceremony but that created the risk that the details would leak. Rather than make the volunteers sign a legal non-disclosure agreement (the conventional approach), Mr Boyle trusted them to keep the secret. The volunteers lived up to their part of the deal, partly because Mr Boyle treated them in a grown-up fashion, listening to their suggestions and ensuring they were paid for their costumes.

By and large, the services sector requires a collaborative approach between workers and managers. If the job requires any kind of creativity, or use of initiative, it is fruitless to attempt to turn the workers into automatons. An interesting example is Timpsons, the British high-street chain that specializes in key cutting and shoe repair. Sir John Timpson, the founder, believes in “upside-down management” which involves trusting the staff to serve the customers in any way they want. They are allowed to change prices and settle disputes. The main two rules are “look the part” and “put the money in the till”.

By and large, the services sector requires a collaborative approach between workers and managers.

Of course, there will always be workers who will take advantage of employers and “swing the lead”. (This metaphor comes from the days when sailors used a piece of lead on a line to check the water depth; lazy mariners would simply swing the lead in the air rather than dip it in the ocean.) In a services-based economy, checking a worker’s productivity is less easy than it used to be; managers cannot count how many widgets they have produced or bricks they have laid.

In some parts of the economy, it can be impossible to improve productivity. An economist called William Baumol described this problem; it takes the same number of musicians the same amount of time to play a Schubert string quartet as it did when the piece was first produced. But despite this lack of productivity improvements, musicians’ wages have risen in real terms over the centuries. That is because those who employ musicians need to offer a wage sufficient to deter them from taking a job as, say, a plumber or a teacher. In a sense, workers in low productivity sectors “free ride” on the back of improvements in more competitive industries.