“Unicorns” are curious — and hiring managers love curiosity

- Being curious is hard because most of what surrounds us regularly is mundane.

- You can learn to find even the most prosaic things interesting — this is what unusually talented people (“unicorns”) do.

- Curiosity is a great way to predict if a candidate will be willing to learn and grow in their position.

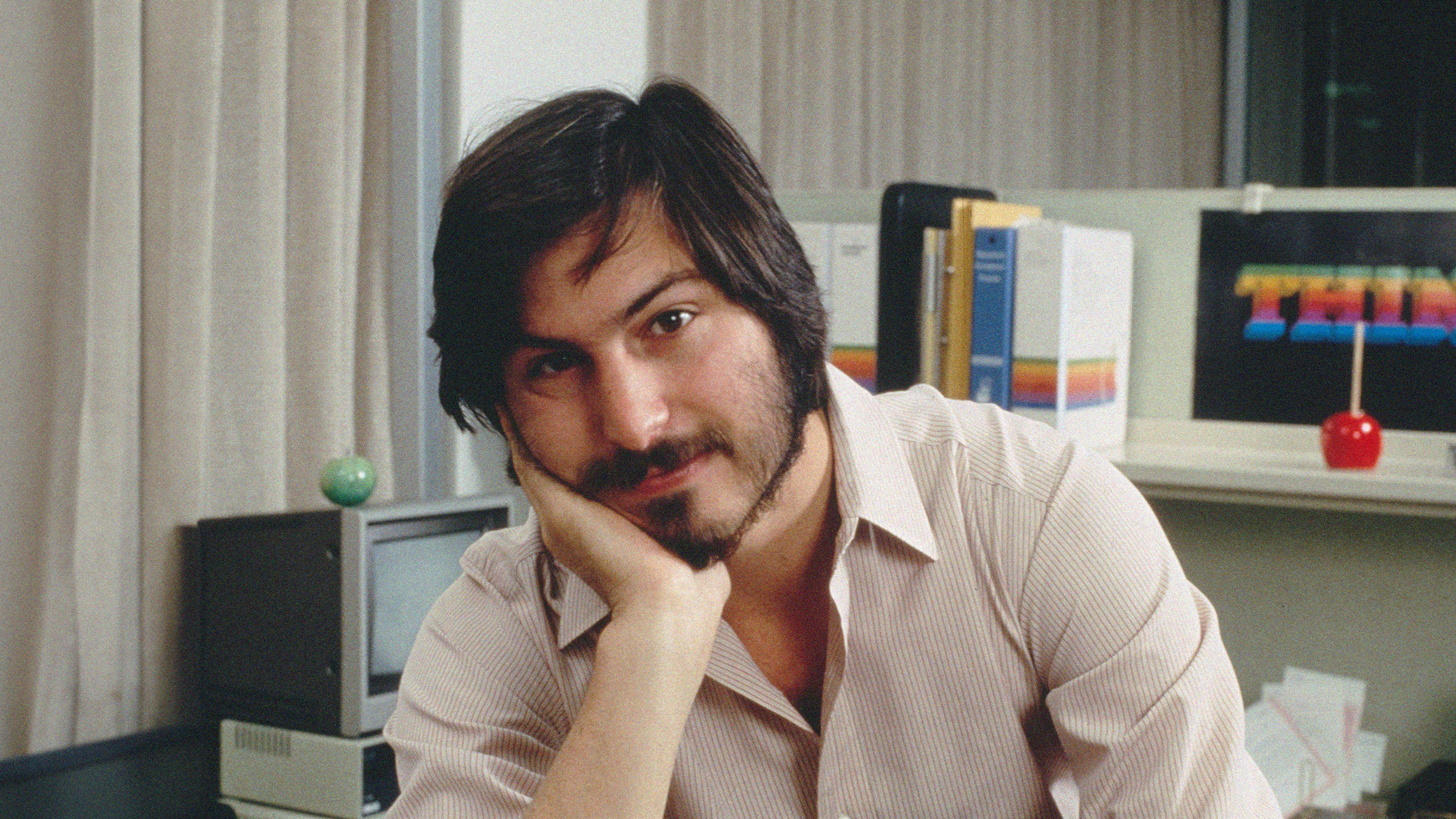

Steve Jobs once said, “Much of what I stumbled into by following my curiosity and intuition turned out to be priceless later on.” Indeed, many of humanity’s greatest minds, from Socrates to Einstein, celebrate curiosity as a key factor of success. But being curious is hard. We’re not being offered potions to drink and rabbit holes to climb into at every turn, after all. And what’s surrounding us on a regular basis is mundane. It’s boring. Can we be expected to simply cultivate curiosity out of nothing?

Absolutely! You don’t need to have curiosity thrust upon you. You can make your own. You can learn to find even the most prosaic interesting, ask questions, and listen to the answers with interest. This is what “unicorns” do. I’ll show you how.

“A person without curiosity may as well be dead,” says Judy Blume. And it’s true. As humans, we’re wired to be curious. In fact, it’s one of the best things about us. From the Clovis people of North America who got here by following that ice bridge in from Asia to those brave souls who literally and willingly launched themselves into space just to see what’s there, curiosity is what we do and what we always have done.

“I think, at a child’s birth, if a mother could ask a fairy godmother to endow it with the most useful gift, that gift would be curiosity,” wrote Eleanor Roosevelt. I think she’s correct that curiosity is the most useful gift — in the top twelve at least. But I also believe that all of us are born with curiosity, no fairy godmothers needed. While many of the other twelve traits of the unicorns are learned over time, curiosity is one that comes as a factory setting.

Science is curiosity in action. Copernicus was curious about the earth’s movement and if it just might be the case that we orbit the sun, ultimately coming up with what is still known as Copernican heliocentrism. Alexander Fleming was curious about the mold that killed the bacteria in his petri dish and discovered penicillin. Rachel Carson was suspicious of DDT’s impact on the environment and started the modern conservation movement when she wrote Silent Spring. The list goes on.

Science is the obvious one. It’s easy to see how science and curiosity pair up for the betterment of all humankind, but scientific discovery is not the only manifestation of curiosity. Curiosity is any time we take a genuine interest in someone, become absorbed with a show on the nature channel, or get caught up in our kid’s research project to the point where they’ve long since gone to bed and you’re doing a deep dive on the use of the portcullis in early medieval European fortress construction. It’s not just science. Curiosity is looking around us and letting our brains be captivated.

Do you know why it feels so good to find out the answer to something you’ve been curious about? Dopamine. Our brains actually reward us for being curious and discovering the “why” of things. It’s dopamine that gives us that buzzy feeling after we’ve looked up why it’s called a binnacle list or what the name of those knicker-like golf pants are called. And who wouldn’t want to chase that thrill again?

When our brains are primed for knowledge by curiosity in this way, we’re also more likely to remember what kind of knowledge is inputted. This discovery is part of the reason why teachers allow students to follow their interests. That fourth grade class might be doing their biography unit in language arts, but each kid is encouraged to research a person who is interesting to them. The outcomes demonstrate that we learn more, care more, and retain more when the subject is something we’re curious about.

Research has also shown that curiosity is good for your mental health. Anxiety, for example, is not compatible with the feel-good, mental high-fiving your brain does when you’re wondering and discovering. Beyond that, the simple act of being curious about something that isn’t yourself can put you in a better mental state. Checking in on a friend or loved one who might also be going through an anxious or difficult time can be enough to derail your own anxiety and give you a dopamine boost from satisfied curiosity.

It’s not always easy to remember to be curious. Life gets in the way. A lot. But as much as you can, follow the advice of author Clarissa Pinkola Estés when she says, “Practice listening to your intuition, your inner voice; ask questions; be curious; see what you see; hear what you hear… These intuitive powers were given to your soul at birth.”

Why hiring managers love the curious

When a candidate is curious, it suggests genuine engagement with your company and interest beyond a paycheck. Curiosity is a great way to predict if a candidate will be willing to learn and grow in their position as well.

Tips for cultivating curiosity at work:

- Give time and budget to team members who want to learn more about a particular subject or skill.

- When challenges come up, practice asking questions before throwing out solutions.

- Take time to get to know your team members on a more personal level by offering optional team lunches and other experiences.