A Show About Nothing: Richard Tuttle’s Mindfulness Masterpieces

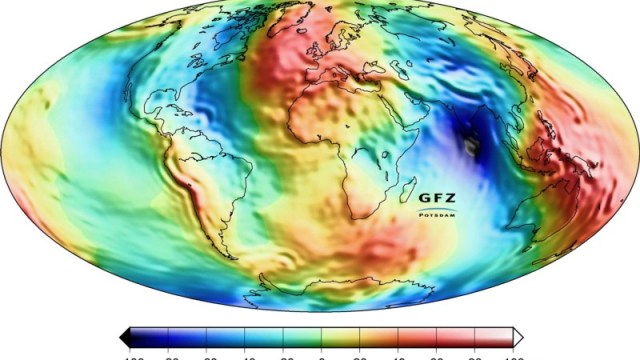

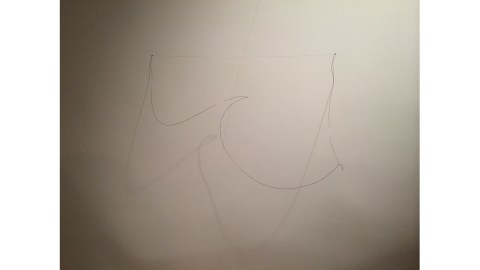

More than 20 years ago, the sitcom Seinfeld went “meta” and joked that it was “a show about nothing.” But 20 years before George Costanza’s epiphany, artist Richard Tuttle was staging shows about nothing featuring works such as Wire Piece (detail shown above) — a piece of florist wire nailed at either end to a wall marked with a penciled line. But, as Jerry concludes, there’s “something” in that “nothing.” A new retrospective of Tuttle’s art at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia, Both/And: Richard Tuttle Print and Cloth, dives into the depths, and widths, of this difficultly philosophical, yet compellingly simple artist who takes the everyday nothings of line, paper, and cloth to create extraordinary statements about the need to be mindful of the artful world all around us.

In many ways, Tuttle’s career begins and flows directly from his first Wire Pieces of 1972. After the excesses of Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, Minimalism offered a quieter, gentler, post-politicized ‘60s alternative. Inspired by friend Agnes Martin, Tuttle sprung onto the bigger art stages with Wire Pieces. Although he’d been working in a Minimalist style since the mid-1960s, something about Wire Pieces and other early 1970s work drew the attention (and disdain) of critics. Curator Marcia Tucker infamously lost her job for staging (and standing by) a controversial 1975 survey of Tuttle’s art at the Whitney Museum of American Art. (Two years later, Tucker founded The New Museum precisely to showcase new, challenging art such as Tuttle’s.)

It’s easy, too easy to stroll mindlessly past Tuttle’s Wire Pieces. You might not even notice them at all — a series of thin wires popping out parabolically to cast shadows on the wall that mix and mingle with lines drawn in pencil. It’s only when you stop and look and allow the multimedia multidimensionality of the pieces to register that you recognize the interplay of lines drawn, shaped, and shadowed. Tuttle installs a new set of Wire Pieces for each location, including this new show, ensuring uniqueness to place and moment. The Wire Pieces hang parabolically not just in the geometric sense of the word, but also in the allegorical sense. Each is a half-drawn, half-sculpted parable teaching the viewer to pay attention to the little things, the fragile “nothings” that speak volumes to those receptive to the lesson.

Both/And: Richard Tuttle Print and Clothis a retrospective of retrospectives — plus. It bundles together “both” Richard Tuttle: I Don’t Know. The Weave of Textile Language(originally at Whitechapel Gallery, London, in 2014) and Richard Tuttle: A Print Retrospective(originally at Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Maine, also in 2014) “and” new prints and the international premiere of new kimono work by Tuttle. Summed together, this retrospective of retrospectives stretches across five decades from the mid-1960s to 2015, almost as long as Tuttle’s relationship with the Fabric Workshop and Museum itself, a collaboration that began in 1978 shortly after the FWM’s founding. Paradoxically, the result is maximum minimalism — the most “nothing” you can find in one place, which oddly adds up to a whole new way of seeing Tuttle, art itself, and the world.

Standing around Ten Kinds of Memory and Memory Itself (1973) at the press preview, Magnus af Petersens, curator of the Whitechapel Gallery Tuttle show, recounted Tuttle’s remark that this careful arrangement of lengths of string on the gallery floor was like a Zen garden, something to be attended and contemplated. Tuttle forces you to attend — be mindful of — everything in the gallery. Just when you focus on the walls, he uses the floor. Just when you focus on the larger pieces, you overlook the tiny, three-inch-long 3rd Rope Piece— art smaller than the numbered wall sign directing you to it. Just when you attune yourself to the tiny and simple, Tuttle gives you the complex Systems that overload your senses with texture, color, and shape and reset your receptors. Every time you think you have Tuttle’s world mapped out, he sends you (in the aptly titled pieces) Looking for the Map once more in vain.

Tuttle’s not an easy artist for the uninitiated (or often more so, the jaded initiate) to embrace. The wide range of visual dynamics — big and small; plain and colorful; here, there, and everywhere — can be disorienting until you appreciate that the individual pieces don’t matter as much as the cumulative effect of making you more mindful of how you are looking. It’s just a length of string until you focus your attention and imagination on it. The texture of cloth, the weave of paper, or the way ink becomes part of a print pass by us daily on the assembly line of our lives, until Tuttle disassembles the machinery of modern existence long enough for us to look, learn, and live again.

Walking through Both/And: Richard Tuttle Print and Cloth, I kept thinking of the books of Matthew B. Crawford, both Shop Class as Soulcraft and The World Beyond Your Head. Crawford sees the modern disconnect with material things in favor of virtual ones as the primary barrier to actualizing the self. Tuttle reconnects us with the material world by calling us to tend the “Zen garden” all around us made of cloth, paper, line, color, and shadow. When life seems like “nothing,” artists such as Tuttle take that “nothing” and magically transform it into “something.” If you want to venture into the world beyond your head, Both/And: Richard Tuttle Print and Cloth is a good place to start.

[Image:Richard Tuttle. Wire Piece (detail), 1972. Florist wire, nails, and graphite. Dimensions vary with installation. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by author.]

[Many thanks to the Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, PA, for providing me with press materials related to and an invitation to the press preview for the exhibition Both/And: Richard Tuttle Print and Cloth.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]