A Survey Shows Why Americans Are Angrier than Ever

“Hmmm. Much anger in him, like his father.” In The Empire Strikes Back(which I watched last week for the first time in decades with my 8-year-old daughter), Yoda expresses doubts about Luke Skywalker’s Jedi training to the ghost of Obi-Wan Kenobi. “He is not ready,” the pointy-eared Jedi master frowns. Anger, and the hatred it breeds, risks turning you to the dark side of the Force. In the world of Dante’s Inferno, anger is a sin that is brutally punished in the fifth circle of Hell. Openly angry souls (the “wrathful”) endure endless assaults on the banks of the River Styx, while those who suppressed their rage (the “sullen”) continually drown beneath its waters.

Movies and literature to one side, anger isn’t terribly good for you. It is bad for your heart. It raises cholesterol. And it tends to make you miserable. Unfortunately, though, anger seems to be on the rise. “American Rage,” a sweeping survey of 3,000 Americans published last week at Esquire, sketches the contours of anger in the United States.

The upshot is alarming, and some details are surprising: “Half of all Americans are angrier today than they were a year ago,” while only 8 percent say they are less angry than they were last year. The Esquire editors point to a number of factors explaining who is angry at whom, and why. Here are five highlights:

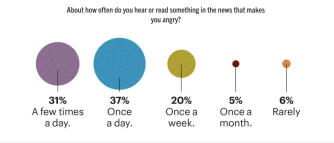

1. The news is a reliable provocation to anger: 68 percent of respondents said they got angry at least once a day after reading or hearing something upsetting in the news:

2. Women are angrier than men. The editors speculate that women tend to be more empathetic than men, leading them to recoil in anger more often when they witness other people being treated poorly.

3. Whites are angrier than blacks. Inverting the spurious stereotype of the “angry black man,” the Esquire survey finds that it is actually white Americans who harbor the most ire: “From their views on the state of the American dream (dead) and America’s role in the world (not what it used to be) to how their life is working out for them (not quite what they’d had in mind), a plurality of whites tends to view life through a veil of disappointment. When we cross-tabulate these feelings with reports of daily anger (which are higher among whites than nonwhites), we see the anger of perceived disenfranchisement — a sense that the majority has become a persecuted minority, the bitterness of a promise that didn’t pan out — rather than actual hardship. (If anger were tied to hardship, we’d expect to see nonwhite Americans — who report having a harder time making ends meet than whites, per question three — reporting higher levels of anger. This is not the case.)” Meanwhile, “black Americans are generally less angry than whites. Though they take great issue with the way they are treated by both society in general and the police in particular, blacks are also more likely than whites to believe that the American dream is still alive; that America is still the most powerful country in the world; that race relations have improved over the past eight years; and, most important in the context of expectations, that their financial situation is better than they thought it would be when they were younger. Their optimism in the face of adversity suggests that hope, whatever its other virtues, remains a potent antidote to anger.”

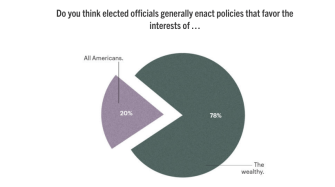

4. Anger toward politicians is rooted in a perception that the government is rigged to serve the rich.

5. Both the rich and the poor are a lot less angry than the middle class. “The least angry household-income brackets: the very rich ($150,000-plus) and the very poor ($15,000 and less). The most angry: the middle of the middle class ($50,000 to $74,999).”

What’s the upshot? If you’re a white, middle-class woman who scans the headlines all day, you’re more likely than not to be among the angriest of Americans. Dante’s punishment notwithstanding, there may be a silver lining to your ire: If you’re mad as hell, you may soon not be willing to take it anymore. In a world that is broken and unjust in so many ways, a little righteous indignation may be just what is necessary to spur a political movement to bring change. Just beware the dark side.

—

Steven V. Mazie is Professor of Political Studies at Bard High School Early College-Manhattan and Supreme Court correspondent for The Economist. He holds an A.B. in Government from Harvard College and a Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Michigan. He is author, most recently, of American Justice 2015: The Dramatic Tenth Term of the Roberts Court.

Image credit: shutterstock.com

Follow Steven Mazie on Twitter: @stevenmazie