Better Late Than Never: Yoko Ono at the MoMA

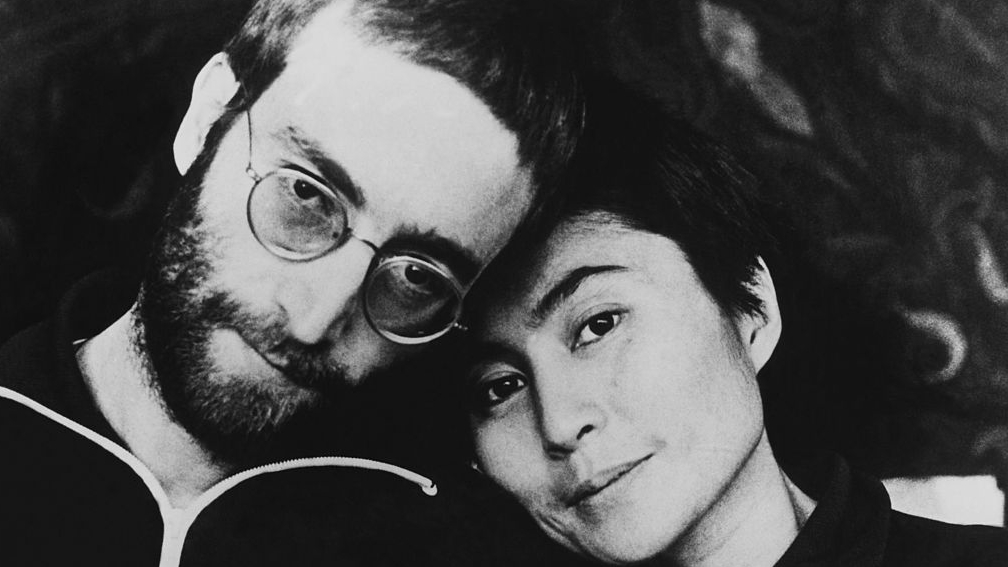

John Lennon liked to joke that Yoko Ono was “the world’s most famous unknown artist.” Before she infamously “broke up the Beatles” (but not really), Ono built an internationally recognized career as an artist in the developing fields of Conceptual art, experimental film, and performance art. Unfairly famous then and now for all the wrong reasons, Ono’s long fought in her own humorously sly way for recognition, beginning with her self-staged 1971 “show” Museum of Modern (F)art, a performance piece in which she dreamed of a one-woman exhibition of her work at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Now, more than 40 years later, the MoMA makes that dream come true with the exhibition Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971. Better late than never, this exhibition of the pre-Lennon and early-Lennon Ono establishes her not just as the world’s most famous unknown artist, but the most unfairly unknown one, too.

Any show involving Ono needs to dig through the rubble of misconceptions to unearth the reality buried beneath lingering Beatlemania. If any one person “broke up the Beatles,” it was their manager Brian Epstein, whose death by overdose in 1967 irreversibly widened already forming fractures in the Fab Four’s collaboration. Like his bandmates, Lennon was already seeking a new path when he walked into a gallery of Ono’s work, met the artist herself, and never looked back. It’s interesting that the MoMA’s staging Yoko Ono right on the heels of the controversial Björk exhibition (which I wrote about here). In many ways, Ono set the standard and blazed the trail Björk and others followed, but none of them suffered for their art on the same scale.

With the Museum of Modern (F)art setting the show’s one “struggling for recognition” boundary at 1971, Ono’s Chambers Street loft performances in the early 1960s set the other. While the Lennon and the pre-Ringo Starr Beatles played their first gigs in Hamburg, Germany, 27-year-old Ono built a performance space out of discarded crates and a borrowed baby grand piano to host musical, visual, and performance artists, erasing the boundaries between those mediums the same way her own work would. Art world luminaries such as Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, Peggy Guggenheim, and Isamu Noguchi climbed the stairs to the Chambers Street loft to witness the rise of Ono and other avant-garde artists of the time between December 1960 and June 1961.

Documents and photos in the MoMA show from that six-month period capture just a hint of the energy and excitement of that time, but you can’t not look at a photo of Lighting Piece (in which Ono would light a match and silently watch it burn out) and imagine Duchamp and Cage nodding approvingly. Ono conceived of Lighting Piece from a childhood practice of sitting alone and lighting matches in a dark, silent room to escape the noises her musical training had made her hypersensitive to. Watching the flames build and then disappear somehow made the troubling sounds fade away, too. Like much of Ono’s art, knowing the background story of Lighting Piece adds a whole new dimension, but you can still connect with the simplicity and drama without it.

The exhibition continues on from Chambers Street to similarly compelling, connecting works, such as Painting to Be Stepped On(1960/1961), literally a painting placed on the floor asking you to step on it, perhaps a comment on how art and artists too often serve as underappreciated and overlooked doormats. Ono encouraged participation in her art as a bridge to greater participation in her causes, especially world peace. As Lennon described in an interview, Ono’s participatory art first attracted him to her and her work. Lennon recalled climbing the ladder to view the tiny “Yes” of the Ceiling Painting (1966) suspended from the ceiling and of asking permission to hammer another nail into Painting to Hammer a Nail(1961). Seeing those two works together in the show reminds you of how much Lennon and Ono’s relationship was truly a “marriage of true minds.”

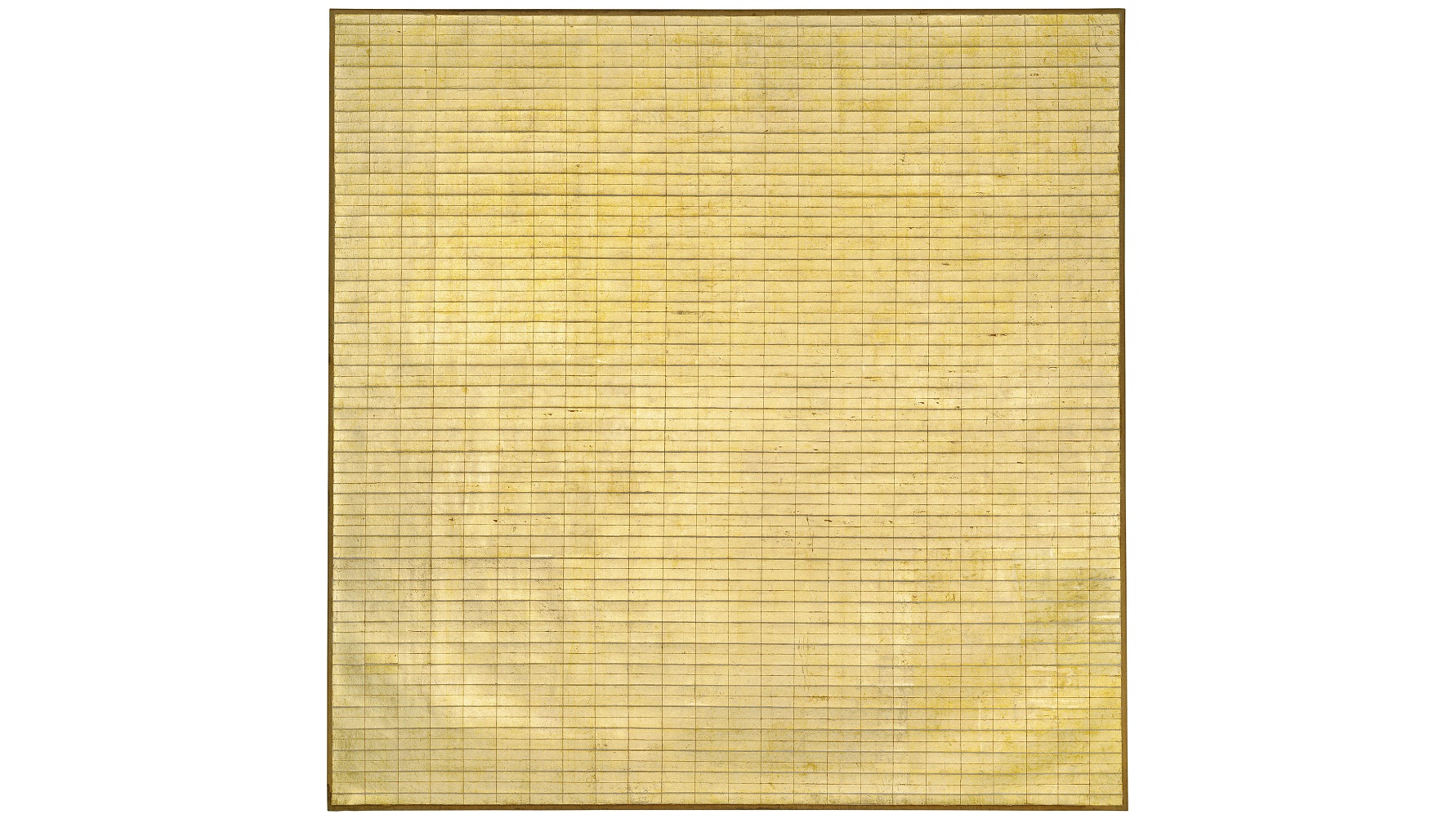

Much of the later work in the exhibition includes Ono’s collaborations with Lennon, ranging from their musical work together as part of The Plastic Ono Band to their political activist work together such as the famous 1969 Bed-Inand WAR IS OVER! if you want it anti-Vietnam War campaigns. The temptation is to allow Lennon to continue to overshadow or at least share Ono’s spotlight, but the MoMA exhibition maintains proper focus on her work, perhaps for the first time. Thus, Grapefruit, Ono’s self-published artist’s book filled with her instruction-based art collected between 1953 and 1964, becomes, like the hybrid-fruit grapefruit itself, a testament to Ono’s personal hybrid philosophy marrying Eastern and Western ideas as well as the book that Lennon said inspired his song “Imagine.”Half-A-Room (1967), an installation of domestic objects sliced in half and painted white, still feels like a strikingly modern dissection of materialism. Film No. 4, 80 minutes of naked, moving bare bottoms, out-Warhols Warhol and reestablishes Ono as a pioneer in the world of experimental film.

But the one piece from this retrospective that cuts to the heart of what we’ve been missing in overlooking Ono the artist is Cut Piece (1964; shown above). Just as the Beatles were invading America with their fun-filled music, Ono seriously confronted full-on issues of sexism and sexual violence in a performance piece in which she asked audience members to step onto the stage and cut away a piece of her clothing with a pair of scissors. Looking at the filmed performance today, it’s amazing to witness the trust Ono places in her audience, who range from women carefully and sympathetically snipping away tiny pieces to men cutting away larger and more sexually explicit sections, including one man who seems to threaten her with the scissors before cutting away a section. Left bared physically and emotionally by the experience, Ono remains strong throughout. Many cite Cut Piece as a foundational feminist performance piece, but the fact that men have also performed this piece testifies to its power as a statement of human resistance to violence, regardless of gender. Like her husband’s song “Imagine,” Ono’s art aims for a universality that defies restricting boundaries.

Like many from a certain generation, I played Double Fantasy over and over after Lennon’s murder on December 8, 1980. A favorite album suddenly became a tragic memorial. I will also confess to getting up to move the record player needle each time to skip the Ono songs that alternated with Lennon’s hits “Watching the Wheels,” “Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy),”and “(Just Like) Starting Over.”Perhaps it’s finally time to start over with Ono and to stop skipping and start listening to an influential, innovative artist hiding in plain sight all this time, waiting for her moment to arrive. Ono may be the most (in)famous Japanese woman of the 20th century, but with Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971, she may finally become the most famous — and respected — Japanese artist, male or female, too.

[Image:Cut Piece (1964) performed by Yoko Ono in New Works of Yoko Ono, Carnegie Recital Hall, New York, March 21, 1965. Photograph by Minoru Niizuma. © Minoru Niizuma. Courtesy Lenono Photo Archive, New York.]

[Many thanks to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for providing me with the image above and other press materials related to the exhibition, Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971, which runs through September 7, 2015.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]