“Birth of a Nation” and the Birth of American Cinema

On February 8, 1915, at Clune’s Auditorium in Los Angeles, California, D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation premiered. The fledgling art form of film would never be the same, especially in America, which even half a century after the end of the Civil War struggled to come to terms with race. Now, a century after Birth of a Nation’s premier, America still struggles not only with race, but also with how race plays out on the silver screen. For good and ill, Birth of a Nation marks the beginning of the first 100 years of the American Cinema—epically beautiful, yet often racially ugly.

We know Griffith’s film as Birth of a Nation now, but at the premier, the marquee read The Clansman, following the title of Thomas Dixon Jr.‘s novel The Clansman, which Griffith used as the basis for his film. Griffith later changed the film’s title to reflect better what he felt was its real story—how America reunited and reshaped itself after the Civil War, rather than the exploits of the movie’s hooded “heroes” on horseback. Everything about Birth of a Nation was bigger than anything ever done before in American film, from the movie’s budget (then $112,000, which would be $2.6 million today [thanks to the 2,243.9% cumulative rate of inflation]) to the then-record $2 ticket price ($46.88 today) to the movie’s box office (a controversial issue in of itself, but at least in the tens of millions in 1915 and hundreds of millions a century later).

Bigger may have not meant better, but Birth of a Nation introduced to a wider audience many new innovations in film. Griffith sought out realism like no other previous director, using consultants from West Point Academy to make the battle scenes as realistic as possible. Many of the uniforms worn by the actors were authentic uniforms used in the actual Civil War. Although Dixon (and/or Griffith) colored real historical events to suit an agenda, the look of those events—battles between armies, Congressional meetings, Ford’s Theater during the assassination of Abraham Lincoln—was undeniably accurate.

In terms of being the father of film grammar, Griffith often gets either too much credit or too little, quite often depending on how you feel about his most famous film. Italian silent films The Last Days of Pompeii in 1913 (co-directed by Mario Caserini and Eleuterio Rodolfi) and Cabiria in 1914 (directed by Giovanni Pastrone) already set a high bar for epics, which Griffith matched and maybe exceeded. Similarly, Griffith didn’t necessarily invent the close-up, the long shot, the moving shot, or fade ins and outs, but he used them to greater effect than ever before, thanks in no small part to his collaboration with innovative cameraman Billy Bitzer.

As an editor, however, Griffith broke free of the prevailing “filmed stage play” paradigm of static filmmaking and employed flashbacks and parallel scenes giving a sense of simultaneous action that made film finally different than live theater, which many still saw as a more refined art form than the lower-class movie house offerings. The quick cuts of movies, television, and even advertising today owe their beginnings in many ways to Birth of a Nation. Similarly, the evocative, inspiring modern movie score has its roots in Birth of a Nation, which featured a full, three-hour score full of original music, contemporary standards such as (the unavoidable) “Dixie,” and classical music such as Richard Wagner‘s Ride of the Valkyries (proving perversely that Wagner wasn’t just for Nazis).

Although he set filmmaking apart from the stage, Griffin knew how to borrow techniques and talent from the stage to suit his purposes. Griffith rehearsed scenes when more bottom-line-minded directors compromised quality for quick production. Lillian Gish, Mae Marsh, Wallace Reid, and other actors in Birth of a Nation went on to have long, lucrative, influential film careers. Directors such as John Ford (as an uncredited Klansman), Raoul Walsh (playing John Wilkes Booth), Jules White (as a soldier extra), and David Butler (as another soldier extra) not only appeared in Birth of a Nation, but also went on to carry the Griffith filmmaking DNA into American cinema for decades in both drama and comedy. The family tree of early American filmmaking could easily be called “Six Degrees of D.W. Griffith.”

So, Birth of a Nation was bigger, possibly better, and more influential than any film made before, but was it popular, box office notwithstanding? Formed only six years before, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) took Birth of a Nation’s heroic depiction of the Ku Klux Klan as a challenge to their fight for equality. Riots broke out in Boston, Philadelphia, and other Northern cities upon the film’s wider release. Authorities in Chicago, Denver, Kansas City, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis simply refused to allow the film to appear in their cities. In response, Griffith changed or cut some offending scenes (whether motivated more by remorse or by lost revenue is unclear), but the damage to the film’s reputation had been done. The elements that made some protest were exactly the same that made others cheer.

The film that Birth of a Nation replaced in America as most controversial says much about movies and the times. On July 4th, 1910, African-American boxing champion Jack Johnson battled the latest “Great White Hope,” former champion James J. Jeffries in “The Battle of the Century.” After Johnson defeated Jeffries on the symbolically chosen Independence Day, riots broke out across America. Filmmakers documented Jeffries training leading up to the fight as well as the fight itself, presumably expecting a different outcome that would have reaffirmed their racial attitudes. When Johnson won, that documentary film instantly became the most controversial footage in the country. (You can see clips here.)

Within three days, authorities across the United States banned showings of the Johnson-Jeffries fight film. Just two weeks after the fight, former President Theodore Roosevelt, himself a former pugilist, in a sudden change of heart, wrote an editorial not just against the showing of fight films, but calling for the end of prize fighting in America entirely. In 1912, Congress legislated a ban against distributing fight films across state lines that would not be lifted until 1940. The sight of a powerful black man pounding a less-powerful white man was something that people were not allowed to see.

In December of the same year that Birth of a Nation debuted, William J. Simmons resurrected the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia, thus riding the wave of popular support gained from the film to overcome federal suppression of the group that dated back to the 1870s, after the events shown in Griffith’s film would have taken place. That previous March, President Woodrow Wilson allowed Birth of a Nation to be the first motion picture shown at the White House, probably as a favor to his friend, the novelist Dixon. Dixon later quoted Wilson as praising the film: “It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.” Whether Wilson really said that or self-promoting Dixon (who took 25% of the picture’s profits for the rights to his novel) put the words in his mouth is unclear. On April 5, 1915, Jack Johnson—harassed by the American legal system for years—finally lost his title to the next “Great White Hope,” Jess Willard; he never received a rematch. A film of the Johnson-Willard fight was quickly released and faced little opposition.

Fast-forward 100 years to filmmaking in America today and you see much has changed. Films such as 2013’s 12 Years a Slave, 42, and 2014’s Selma show great progress. Yet, when it came to 2015’s Oscar nominations, African Americans found themselves on the outside looking in. Currently, the most controversial (and commercially successful) film is American Sniper, a film that, like Birth of a Nation a century ago, strives to tell us the history we might want to hear rather than the history we need to hear. Should we ban such films, similar to how Germany has banned Nazi-era propaganda films, or should we see them, as Richard Brody perceptively writes of those Nazi films, as “symptoms, not causes.” We can’t, and shouldn’t, “unsee” films such as Birth of a Nation and the ideas they give visual life to. But we can see such films and ideas for what they really are.

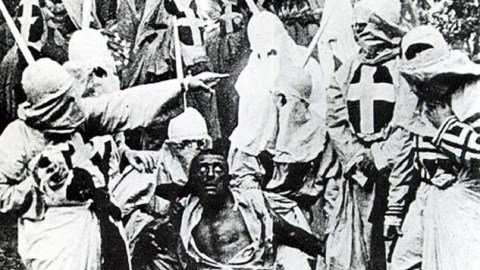

[Image: Hooded Klansmen catch the “renegade” former slave Gus, played by white actor Walter Long in blackface, during the days of Reconstruction. Image source:Wikipedia.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]