Forget Da Vinci, Try Solving the Piero della Francesca Code

Fans of Dan Brown (and Tom Hanks) hoped to get an education in the Italian Renaissance along with their beach reading (and movie-going) of The Da Vinci Code. But they and those who think that Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Donatello are just Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles are missing out on a Renaissance master of art and mathematics just as captivating and mysterious as Da Vinci—Piero della Francesca.

In Piero della Francesca: Artist and Man, James R. Banker relies on newly discovered documents and years of study of the Renaissance to crack the “Piero Code.” You won’t run across the Knights Templar or unearth the Holy Grail in Banker’s biographical study, but you will come away with a real-life detective tale compellingly told and a greater understanding and appreciation of an artist whose art may look otherworldly but, as Banker suggests, grew directly from Piero’s hometown roots.

Piero grew up in Sansepolcro in the Tuscany region of Italy, only 4,500 people strong at his birth around 1412. Literally “Holy Sepulchre,” Sansepolcro took that name when two founders brought a stone there from the Holy Land’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which itself was built on the spot where Jesus Christ reportedly died, was buried, and rose from the dead. “How, then,” Banker asks, “did this young man from a provincial town 79 miles west from Florence and 169 miles from Rome and without an extensive formal education become, along with Leonardo da Vinci, both an outstanding geometrician and the most intellectual painter of the Quattrocento?”

Like Shakespeare’s origin from the sleepy hamlet of Stratford-upon-Avon, Piero’s origin story sounds impossible, at least until you look beneath the surface and accept the resources a determined aspiring artist could find in even the unlikeliest of places. “Piero’s education in the mixed merchant-artisan culture of Sansepolcro remained a vital element in his painting and writings until his death,” Banker argues, “influencing the language he used in his vernacular treatises, and evident in the deep respect that he retained throughout his life for the beautiful products from the hands of artisans, whether clothing, leather book bindings, gems, or veils.” Piero came from a long line of leather workers (and broke his father’s heart pursuing painting rather than joining the family business), so whenever you see a leather good in one of his paintings rendered with sensitivity and reverence, it’s a homecoming of sorts.

Banker struggles mightily with the shoddy surviving documentation of Piero’s life, which begins with the mystery of the year of his birth and continues throughout much of his life. We glimpse Piero’s whereabouts throughout his career secondhand through documented commissions, appearances as a witness in Sansepolcro legal papers, and other fragments of history that Banker meticulously brings together. Banker stays hot on Piero’s half-century-cold trail as the artist travels through Florence, Modena, Ferrara, Rome, and other cities in Italy and absorbs the influences of Brunelleschi, Masaccio, Donatello, and other contemporaries, plus the lessons of classical sculpture from newly discovered Ancient Roman artifacts. Banker calls the 1440’s Piero’s “lost decade” during which he painted little, but learned much. Banker pieces together the known dates of Piero’s movements, the artists he would have seen or met in those places at those times, and Piero’s paintings reflecting those influences to give us the best available picture of Piero’s progress as a provincial pilgrim through the heart of the big-city Renaissance.

By the end of these adventures, Piero arrives at what Banker defines as his “classical style of fully sculpted monumental figures with more gravitas than emotion in meticulously constructed perspectival space.” Aside from his wonderful detective work, Banker digs deep into Piero’s greatest hits to show how that “classical style” plays out in the work. Anyone familiar with the strangely otherworldly Flagellation of Christ knows how Piero uses, in Banker’s phrase, “incredibly deep perspective… rational in its organization of a complex set of spaces and shapes” to pull you into a theater of the imagination past the trio of men conversing at the surface of the work into its innermost depths where Christ is suffering the first stages of his passion and death. The late Brera Madonna stands as “a virtuoso example of Piero’s command of all his earlier techniques” such as using light to define figures and mathematical perspective to give the heavenly an earthly reality. “Despite the monumentalizing epic within which Piero’s figures act,” Banker asserts, “they are within the world of human possibility.” They may not have the drama of a Michelangelo figure, but they do display the gravitas of real people facing extraordinary events.

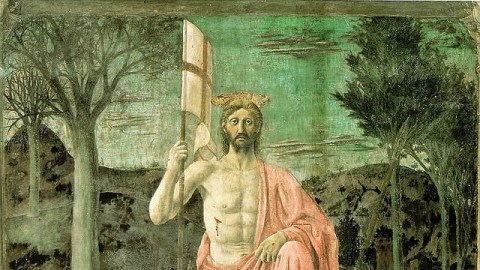

Aside from Piero’s technical skill and innovations, he approached his art and his subject with a perspective unique to the time. “For Piero, the Divine had to be on the plane of the human, the natural, and the historical,” Banker writes. When Piero painted the Madonna della Misericordia for the local Sansepolcro confraternity of laypeople dedicated to charity, he placed a group of everyday people physically under the protection of an oversized Madonna, who spreads her cloak around them. Later, Piero painted The Resurrection of Christ (detail shown above) in the Sansepolcro communal meeting house. “[T]he Resurrection served a civic function,” Banker says, “confronting the legislators whenever they considered what laws would promote the well-being of the townspeople of the Holy Sepulcher.” Piero paints Christ rising from the tomb triumphant and as judge and lawgiver of the people. Thus, The Resurrection of Christ combines “the eternal verities” of medieval art and the specific moments of Renaissance art to arrive at a powerfully poetic and pivotal moment in the history of art as well as history itself, as Italians learned to assume some democratic rule after centuries of warlords and chaos. The mystery of Christ’s assertive stare isn’t spiritually separated from life on Earth but rather a connection strung between faith in God and faith in humanity. Banker’s ability to connect to this connective quality of Piero’s art cracks the true Piero code and resurrects the artist in a way that no trove of documentation can.

This past summer Americans literally saw “Art Everywhere” as that campaign plastered fine art across the country with works such as George Tooker’s 1950 painting The Subway. Tooker idolized Piero della Francesca in his updating of the master’s deep perspective and sculpted figures for a modern audience. Sadly, Piero fell out of critical favor after his death until the early 20th century, when the Cubists tried to incorporate the mathematical aspects of his art into their own. Allied bombing during World War II almost destroyed much of Piero’s art (and Sansepolcro itself) until British officer Tony Clarke halted fire after remembering a 1925 essay by Aldous Huxley mentioning that little town as the home of the greatest painting in the world, The Resurrection of Christ. James R. Banker’s Piero della Francesca: Artist and Man reminds us that, despite the centuries between us and Piero and the fact that we frequent subways more now than cathedrals, the human scale of his art—the ability to have his divine characters look us square in the eye as our eyes square up the mathematically intense realism of his worlds—never gets old. It might not be the Holy Grail, but the “Piero Code” is something we can all hold on to.

[Image:Piero della Francesca. The Resurrection of Christ (c. 1463), detail. Image source.]

[Many thanks to Oxford University Press for providing me with a review copy of James R. Banker’s Piero della Francesca: Artist and Man.]