Like a Rolling Stone: Was 1965 the Most Revolutionary Year in Music?

What do “Yesterday,”“Satisfaction,”“My Generation,”“The Sound of Silence,”“California Girls,” and “Like a Rolling Stone” all have in common? They were all hits in 1965, the year author Andrew Grant Jackson calls “the most revolutionary year in music.” In 1965: The Most Revolutionary Year in Music, Jackson weaves a fascinating narrative of how popular music and social change influenced one another to create a year memorable not only for great music, but also for great progress in American culture. In this whirlwind tour of multiple genres of music as well as multiple pressing political issues, Jackson states a compelling case for 1965 as a key turning point in American music and society as well as provides a mirror for how music and society interact today, 50 years later.

A confirmed “Beatlemaniac” at four years of age and author of Still the Greatest: The Essential Songs of the Beatles’ Solo Careers, Jackson centers much of 1965 on the evolution of The Beatles based on the six (!) number 1 U.S. singles they posted between January 1965 and January 1966. Beginning with “I Feel Fine” and “Eight Days a Week” “matching the optimism both of America rebounding from President [John F.] Kennedy’s assassination and Britain proud to be the swinging capital of pop culture,” Jackson follows the “melancholy” of “Ticket to Ride” and rides it down to the desperation of “Help!” as the violence of Vietnam and Watts escalates. Next, “[t]he desolate ‘Yesterday’ resonate[s] with millions who [feel] a stable past … crumbling in the face of social upheaval,” to which “We Can Work It Out” — the year’s sixth and final chart topper — offers hope for resolution.

That progression might seem too neat and orderly as a Beatle-esque barometer of historical developments, but Jackson works it out wonderfully and convincingly. As shorthand for social history, especially for the 1960s, number one hits work as well as any other framing device. But for Jackson, the music is much more than a framing device. “I guess the ’50s would have ended in about ’65,” Jackson quotes Bob Dylan, another central figure of 1965. Whereas others see the 1950s dying with Kennedy’s departure in 1963 or The Beatles arrival in 1964, Jackson, like Dylan, targets 1965, when the escalation of troops in Vietnam, the escalation in racial tensions that lead to the Voting Rights Act, and the escalation in changing identities for women (thanks to “the Pill”) and men (thanks to “long hair” and other gender-bending freedoms), as the time when America truly turned a corner from the Age of Eisenhower to the Age of Aquarius.

Jackson’s juggling act of musical and social history is a wonder to behold. He provides a helpful chronology of musical and historical events in the front of the book, but nothing can prepare you for the mad mixing of genres and influences throughout. Jackson’s eye for eye-opening detail and telling anecdotes makes for entertaining and addictive history, especially for those who can hear the soundtrack of 1965 playing in their head as they read. More than just music, 1965 puts you on Edmund Pettus Bridge on “Bloody Sunday” as well as in Andy Warhol’s Factory, where he “rebelled against the rebels by saying he liked plastic” forms of commercial culture, if only to adopt and subvert them.

Unlikely musical bedfellows, such as Buck Owens, James Brown, Sonny and Cher, The Grateful Dead, The Lovin’ Spoonful, and Frank Sinatra, all find ways to cross-pollinate and provide “the hybrid vigor,” as Jackson puts it, to create this golden year. Jackson even manages to make clear the relevance of John Coltrane’s “sheets of sound” jazz in 1965, something that seems almost impossible for jazz to accomplish half a century later. If I have one small bone to pick with Jackson’s musical-social historical mash-up, it’s that he’s unable to achieve the same kind of relevance for classical music that he does for jazz and country in 1965. There’s a good reason why The Beatles stuck experimental classical composer Karlheinz Stockhausen on the cover of Sgt. Pepper, so I wish that he could have found a place in Jackson’s history. (Even John Cage gets only a passing mention in the context of Yoko Ono meeting future husband John Lennon.) But Jackson can be forgiven for not being even more encyclopedic about a single, tumultuous year than he already is.

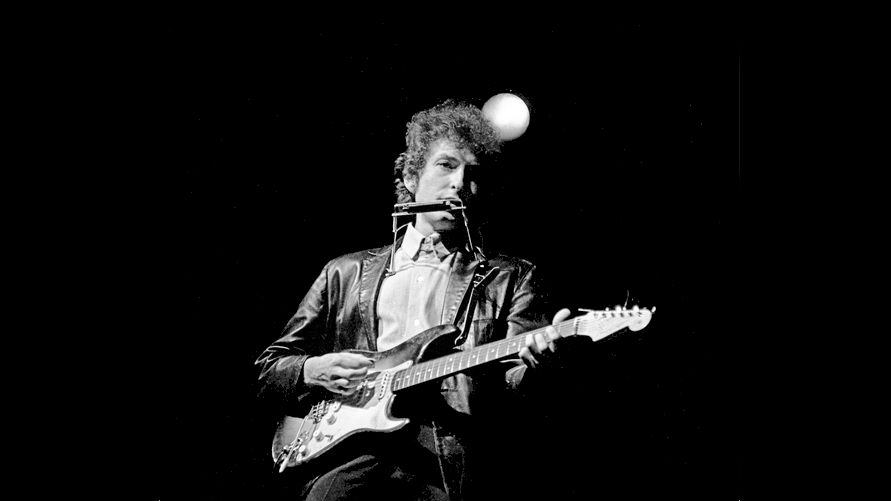

Where Jackson really excels is not in chronicling 1965 as much as in showing how it is a turning point. With songs such as “Get Off of My Cloud,”The Rolling Stones (shown above) positioned themselves as the “anti-Beatles” in the sense of rejecting pre-1965 pop music for something more authentic and anti-authoritarian. (The Beatles would become “anti-Beatles” in a few years themselves.) Jackson sees Mick Jagger not just as “the forefather of the glam rock era,” but also a pivotal figure in the gay rights movement of today as an androgynous activist simply by being his outrageous, unrestrained, label-defying self. Jackson calls Jagger and other game-changing musicians of 1965 “walking science experiments for the wholesale reconsideration of values in Western society: which limits were worth breaking (racism, sexual repression, homophobia) and which perhaps made sense (restrictions against harder drugs).”

Jackson’s science experiment metaphor made me long for the days of such bubbling cauldrons of socially relevant music across all genres rather than the bubblegum pop of today. Will someone 50 years from now point back to “Shake It Off” as a turning point? All apologies to Taylor Swift, but most likely not. In the epilogue to 1965: The Most Revolutionary Year in Music, Jackson quickly catalogues the reversal of 1966, when the liberating excesses of the previous year met the conservative restrictions of a roused “silent majority” that would go on to elect Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan. As Jackson points out, 1965 witnessed a lot of great music, but also the end of Reagan’s acting career as he turned to politics full time, beginning a chain of events that shape America still. You may not agree that 1965 is the most revolutionary year in music, but you can’t argue with Jackson’s proposition that American life — musically or socially — hasn’t been the same since.

[Image:The Rolling Stones perform in Munster, Germany, on September 11, four days after recording “Get Off of My Cloud” in Hollywood. From left:Charlie Watts on drums, Brian Jones on guitar, and Mick Jagger. (Courtesy of the Associated Press/Schroer)]

[Many thanks to Thomas Duane Books/St. Martin’s Press for providing the image above from and a review copy of Andrew Grant Jackson’s 1965: The Most Revolutionary Year in Music.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]