Neither Face Nor Feelings

No carnefab Manager liked hearing from an NFA Inspector, but especially not when the message said, “Fieldspec high neuro count. Site audit 213245-1330. Pres Req.” Paul Ingersoll read the message and checked the time. 213245-1312.

“Shit,” he muttered. He barely made it to the factory floor before the Inspector arrived and gave Paul the lot number from the batch in question.

“Restaurant stock, Mendocino,” he explained. “Chef reported a twitcher.”

Paul checked the number, heart sinking – one of their “perfect” batches with ideal genetics. Every vat in this factory was churning out a thousand kilo slab that had been born from those cells. Now the government said every batch from that lot might be useless. No. Not might. Was – if the Inspector’s results confirmed the chef’s report.

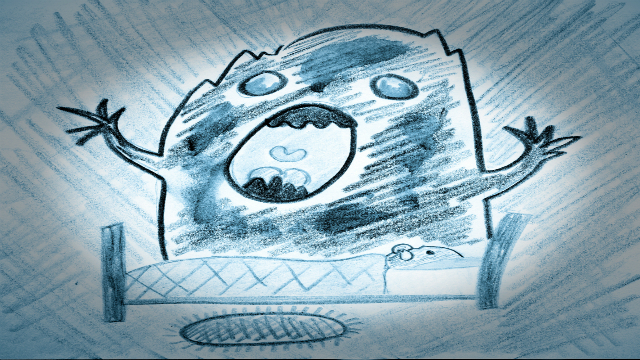

The Inspector was already at the nearest vat, a large, open-topped box full of pinkish liquid. Inside sat a rectangular red slab, riddled with veins and marbled with fat. This slab was only at five hundred kilos, so had a few weeks to go, and had never given any indication that it was anything but an entirely senseless block of artificially grown meat, built from cells that divided without consciousness. That was the point – to produce meat with neither face nor feelings. It had worked for nearly a century, except for the two times that it hadn’t, both long before Paul had been born.

The Inspector pulled out a wand and touched it to the slab. There was a blue flash and snap and the slab twitched along its entire length. “Okay,” Paul thought, “Not world end without genetics,” although he knew he was lying to himself.

The Inspector tapped his forearm repeatedly, sending notes to a government computer. Then, emotionless, he pulled out a biop kit, dipped a finger on each hand into a vial of blue goo that grew sterile gloves up to his wrists, sprayed anesthetic on the slab and proceeded to gingerly poke it with a rod that plucked out a small cylinder five millimeters wide and deep. He stuck the rod into a hole in the biop kit case, then sprayed the wound with healer. By the time he peeled off the gloves, the results came back, Paul feeling ill as he waited for the hammer to fall.

“Neuro count exceeds Fed Regs by one hundred sixty parts per million,” he finally said. “Recall ordered for every batch from this lot. You retire the rest. We confiscate the original germ lot. Sig off inspection and results, please.”

The Inspector held out a flat pad and Paul touched his palm to it. What else could he do? They had been producing bad meat and nobody noticed. It probably wasn’t in the original germ lot, but mutations were always possible, and so were deviations with stem cells that decided to grow into

something besides meat, fat, veins and red blood cells that were kept oxygenated by the vats. Still, stem cell deviations generally led to things like hair or teeth, sometimes a hoof. They rarely led to the development of brain cells – so rarely that this was only the third time it had happened, and Paul Ingersoll was the poor unlucky son of a bitch in charge of the factory where it happened. Had been in charge. All the recalled meat that wasn’t already dead would be euthanized. The meat in this factory would be retired, the employees held on retainer until a clean germ line was brought in. Paul, however, would be transferred. Not retired, and not laid off. He would carry the responsibility for this problem for the rest of his career, which was a long time, since he was only twenty-seven.

** *

The warehouse known as “The Old Cows Home” covered thirty square kilometers in the California desert. Inside were endless rows of swimming pool-sized vats where retired meat went to live because nobody was sure whether it was aware or not and nobody wanted to take the chance that it was. Perhaps the bad meat that had already been sold was lucky. Even if it did develop consciousness, four minutes out of the vat without oxygen would have killed it or severely damaged any sort of brain, so it was easy to think of as dead, and no one would feel guilty if tasked to destroy it.

The retired meat was not so lucky, and neither were the people who had to deal with it. It had to be treated like a living thing, brought from the vats to the warehouse on life support, then re- installed in the larger vats, to be left for… nobody knew how long. The lots already here had arrived thirty-eight and sixty-two years previously, and were still going strong and growing. Each vat started with one slab, the size of an adult cow. The oldest slabs had filled half their 2,500 cubic meter vats, and it was time to worry about what to do when they started to outgrow those. Thanks to the Compassionate Food Act of 2034, amended 2070, killing the slabs would be murder; letting them die, negligent homicide. Paul’s job now was as one of the nurses to all this meat that would have been food had it not developed nerves and at least some rudimentary feelings. Maybe.

Everything was predicated on “Maybe.” Maybe this meat felt pain. Maybe not. No one knew because the world of 2132 was black and white, either/or, and the only way to answer the question was to commit a prohibited act. As long as there was any chance that these inanimate slabs of protein might experience an unpleasant sensation, the question was considered answered, and the answer was, “They are our responsibility for as long as they live.”

If they ever became sentient, and vengeful, Paul hoped that they would understand – they had been created out of the desire to feed the planet humanely.