Great Pacific Garbage Patch is now three times the size of France, research suggests

Where does a plastic straw go after someone litters it on the sidewalk?

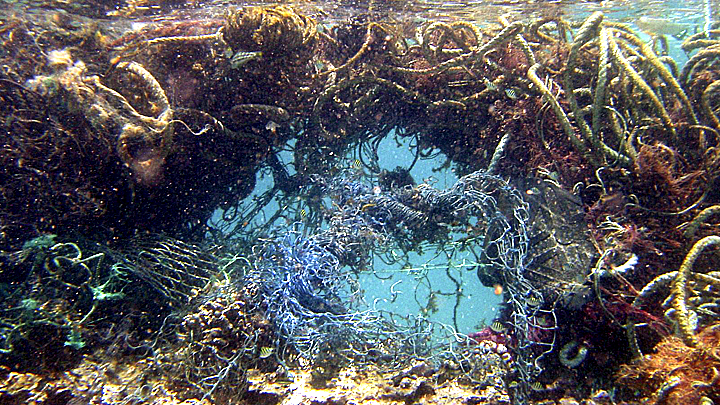

Often, that piece of plastic will make its way down a storm drain, then into a creek, a river, and finally into the ocean where, in many cases, currents carry it to where billions of other plastic pieces end up: the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an area of concentrated trash between California and Hawaii that spans three times the size of France.

The garbage patch was first discovered in 1997 when oceanographer Charles Moore and his crew sailed through it in one of the most remote regions of the Pacific Ocean.

“It seemed unbelievable,” Moore wrote in Natural History. “But I never found a clear spot. In the week it took to cross the subtropical high, no matter what time of day I looked, plastic debris was floating everywhere: bottles, bottle caps, wrappers, fragments.”

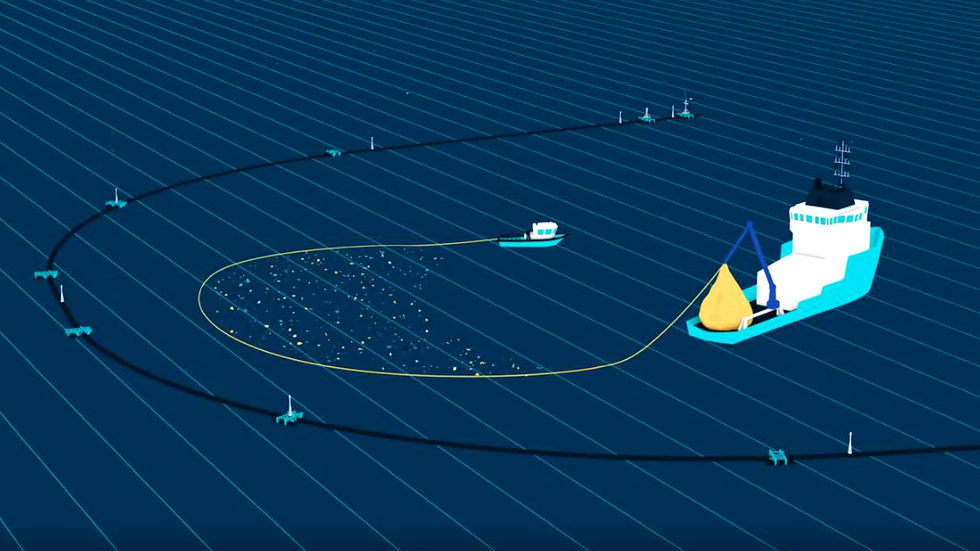

A three-year study published Friday in Science Reports shows that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is larger, growing faster, and has different characteristics than researchers previously thought. Most notably, the results showed that the patch takes up about 1 million square miles – four to sixteen times larger than previous estimates. Worse, it appears to be growing exponentially.

Everything there is to know about our new research on the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, in 1 minute. Learn more on https://t.co/eWQgxo4ZLPpic.twitter.com/J1gRHdJmKb

— The Ocean Cleanup (@TheOceanCleanup) March 22, 2018