Andy Warhol’s Masturbation Metaphor

In a 1977 interview with Glenn O’Brien for the marijuana lifestyle magazine High Times, O’Brien asked Andy Warhol if his teachers recognized his early “natural talent.” “Something like that,” Warhol responded with his characteristic unconventionality, “unnatural talent.” Warhol’s “unnatural talent” quip alluded not only to his mass-produced, machine-like paintings of soup cans and silk screen portraits, but also to his sexual orientation— the “unnatural” life of a homosexual. Just as Warhol turned that verbal double play, art scholar Michael Maizels tries to touch those two bases of Warhol’s art in “Doing It Yourself: Machines, Masturbation, and Andy Warhol” in the Fall 2014 issue of Art Journal. For Maizels, the way that Warhol made art reflected the way Warhol lived his life as a homosexual male in late 20th century America. When we look at Warhol’s art, Maizels suggests, we should see not just a critique of commercialized society and its art, but also a critique of that same society’s sexual tolerance.

Maizels, a teacher, curator, and scholar who focuses on the legacy of the art of the 1960s, begins by laying out the history of Warhol studies. “Until the middle of the 1990s, readings of Warhol’s work typically focused on its engagements with the societal shifts of the mid-1960s — for example the rise of commodity consumption and celebrity culture — and the extent to which Warhol was either critical of or complicit in these changes,” Maizels explains. “However, beginning with the 1996 publication of Pop Out: Queer Warhol, art historians have increasingly argued for considering questions of sexual practice and identity as central to Warhol’s art.” Building on that scholarship, Maizels “conten[ds] that ‘the commodity Warhol’ and ‘the queer Warhol’ were bound up in one another to an extent that has not been sufficiently appreciated — linked by imagery as well as through their means of production.”

Essentially, Maizels sees Warhol as commenting on the perception of his homosexuality as “unnatural” and “non-productive” through the similar, almost invited perception of his art as “unnatural” and “non-productive” because it increasingly diminished the presence of the human hand. Exhibit A for Maizels’ case are the five paintings Warhol made between 1962 and 1963 that he collectively titled his Do It Yourself series. These five paintings — two still lifes, two seascapes, and one landscape — mimic the “paint by number” kits first popular in the 1950s. In terms of content, Warhol’s mimicry “is … typically read as commentary on the increasingly commodified nature of artistic production,” Maizels argues, but “their collective title can also be read as a thinly veiled reference to masturbation.”

As Maizels points out, the language historically used to denounce industrialization (and more recently in the 1950s used to criticize the aesthetics of painting by number) as an unnatural threat to natural human skill and productivity sounds a lot like the language traditionally used to denounce homosexuality as an unnatural threat to heterosexuality and human reproduction. “As same-sex desire has historically been denounced by analogy with the machine — as unnatural, involuted, and sterile,” Maizels writes, “Warhol’s embrace of mass production became a way to stake out an aesthetic that celebrated the qualities of repetition, sterility, and immanence in much the way that traditional, heteronormative criticism trumpeted singularity, fecundity, and universality.” In response to a world that rejected him personally, Warhol created a kind of art that rejected that world’s premises in turn not only about what is “normal,” but also about what is “art.”

As Maizels rightly points out, the reigning picture of a “natural” American artist in the 1960s was Abstract ExpressionistJackson Pollock, a man who once boldly announced, “I am nature.” The brash, boozy, man’s man “Jack the Dripper” thus serves as the face of the “historical construction of the hypervirile masculine artist” critiqued by Warhol in his “mocking the notion of artistic creation as akin to heterosexual coitus.” The Do It Yourself double entendre thus uses the masturbation metaphor to reject the idea of a “normal” artist or a “normal” person as a Pollock-esque hyper-hetero. Every Warhol paint by number, soup can, or silk screen can therefore be seen as a defiant self-portrait on multiple levels.

In the end, Maizels cautions that “[t]his is not to suggest that Warhol was expressing an essential connection between masturbation, homosexuality, and mechanical fabrication, but rather that he mobilized and obliquely sought to reclaim these terms that had been derided together through similar language.” Warhol’s soup cans and silk screens aren’t about masturbation specifically, but rather strive to break the link forged in the popular imagination between masturbation, the acceptance of sexual difference, and industrialization. Thus, when Warhol famously remarked, “I want to be a machine,” he could just as easily have announced, “I want to be accepted for who I am.” Maizels’ article brings fresh eyes to Warhol’s most familiar, too familiar artworks and raises interesting questions still vital in this age of same-sex marriage regarding what direction America will take in the civil rights issue of our time.

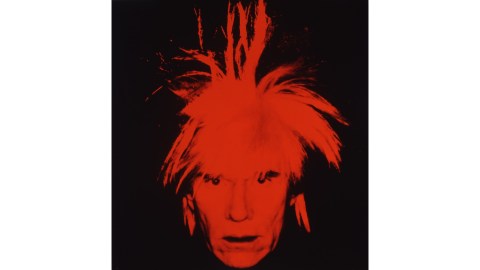

[Image:Andy Warhol. Self-Portrait, 1986. Image source:WikiArt.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]