How David Small’s experience with therapy in adolescence inspired the cathartic self-analysis of his memoir, “Stitches.”

Question: How did “Stitches” come about?

rnDavid Small: It started as an act of self-therapy, really. I found that I had reached over half a century of life, and that I was still, in spite of the fact that I have a perfect career doing something I really love to do, a wonderful home, a wonderful, wonderful marriage, friendship—and in spite of all of these things I was having dreams and sometimes anxieties and exhibiting a kind of erratic behavior that showed quite clearly that I was still on some level a troubled lad of 14, or even younger. And I had always wanted to write maybe stories or something relating to some things that had happened to me as a young man, but I never thought that there was a full memoir or even a possibility of a book in there. But I did have this need to go back and to see my youth again. What I really wanted was, I really wanted to go back into psychoanalysis. I'd had a wonderful analyst, who's in the book, for 12 years when I was a young man. But I wouldn't call it deep Freudian analysis because I was so young. My analysis really was going to an office, first five and then three times a week for many years, and sitting down with a man who actually was, for me, a perfect parent, somebody who just allowed me to be myself, who loved me for who I was, and just allowed me—and he really did love me; I think that's why it was so effective. He really cared for me. And because I had no voice, he had to speak for me.

rnSo the talking cure in my case got reversed. It was the analyst that did all the talking, telling me what was probably, he thought, going on in my mind. And as it turned out many years later, because of the similarities in our experience, he did understand me very, very well. But you know, being able to sit with somebody who was patient with me and sympathetic and empathetic, and who would allow me to act out my fears and so on, and who didn't despise me for it—you know, that's really what saved me as a young man. And I wanted that back; I wanted to do it again. You know, I was, I think 55, maybe 10 years ago, when I first started longing to go back. And I also—I wanted it back fully. I didn't want to just be going to see a therapist, and—you know, I wanted that kind of relationship. But the fact is, I live out on the edge of a prairie out in Michigan, in a very rural setting, hundreds and hundreds of miles from that kind of help. I'm not even sure I have health insurance that would cover it. So I finally realized, after yearning for it for so long, this impossible thing, that if I was going to have it, I was really going to have to give it to myself. And that's what I did: I started sitting down and, first in prose and then later on in pictures, tried to write out what had happened to me as a kid. And I tried to imitate what my old analyst had done for me. I was patient as I worked through all this mess of memories, which of course came back with no—you know, memories aren't chronological; they didn’t come back in any logical order. But I just let that happen; I let it flow. If I had dreams that I had—if I suffered from a dream that disturbed me at the time, I would write it down as I usually do and try to—and then to draw it out—when it started becoming a graphic thing. And so I was trying to be like my doctor; I was trying to be patient and sympathetic, and yet not totally tolerant, you know. There was always an expectation that I would get through this. And then later on, when I had a contract from a publisher, that was another spur to get through it, to get to the end. And that's the way it developed; that's the way it started. It didn't really start as a book; it started as therapy.

rnQuestion: Did the book force you to confront painful buried memories?

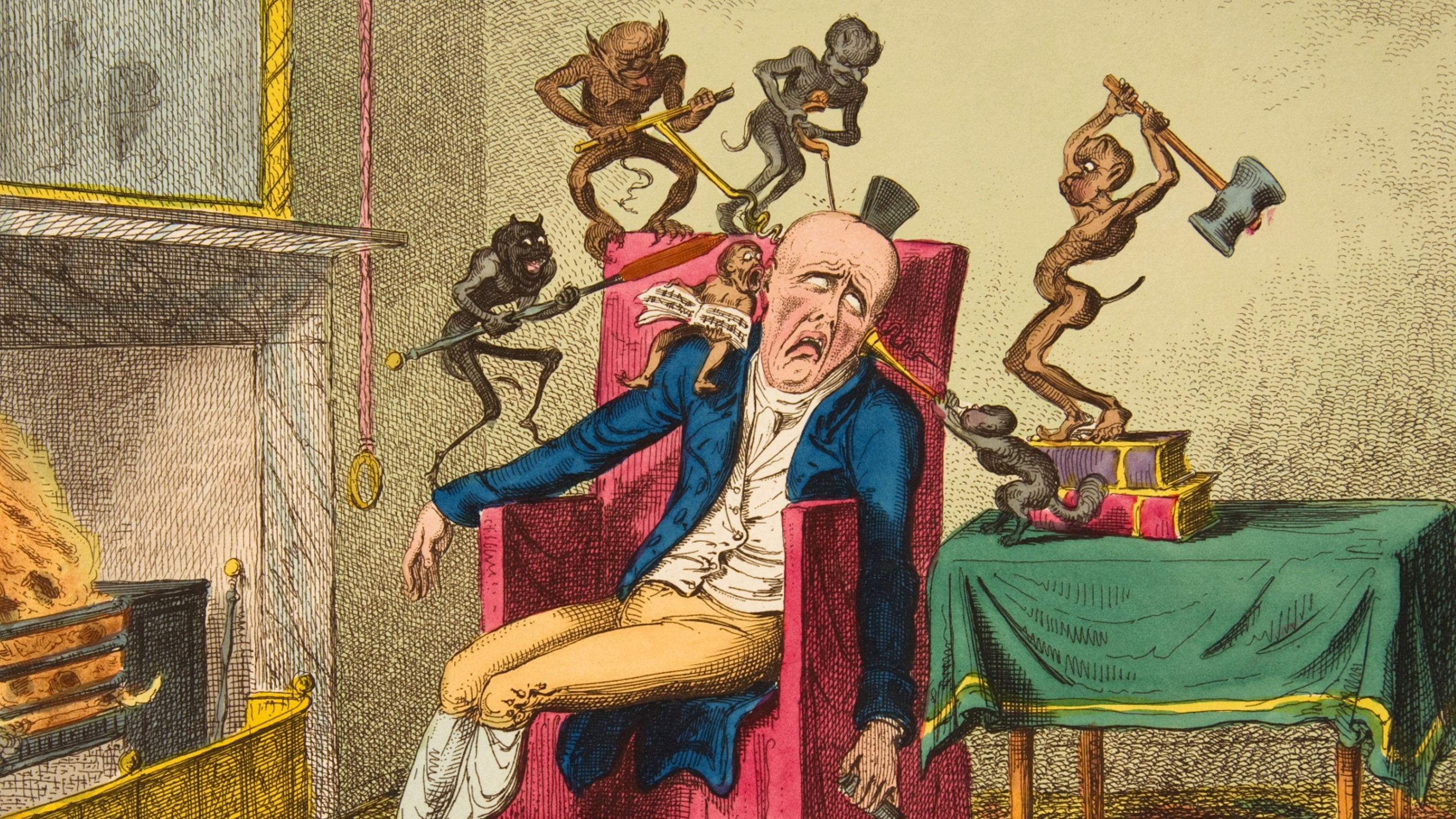

rnDavid Small: I think the worst thing, the worst part, was when I started drawing things out they really got real for me. As long as I was doing it in prose, there seemed to be kind of a scrim between me and the experiences that I was remembering, shadows moving behind an opaque screen. But when I began to draw especially my mother, when I saw her face on the page, and when I realized that I could draw her from any angle, and really brought her back with all of her—that aura that she had—it was as if she was with me again. It was as if I had really brought the ghosts back, and I began to get very, very anxious, because even after the age of 50 it was impossible for me to see my mother as a human being. I felt she was a monster, and she had subtly been influencing my behavior and my thoughts and my dreams for so long that she was kind of a monster; she was a demon. And when I brought her back to life, I could feel that malevolent presence around me again, that woman who was totally incapable of giving nurturing to anybody, and, you know, her selfishness and her withdrawn indifference to everything but her own needs. And I began feeling these feelings of anxiety that I used to have when she was alive, and especially when I was a teenager. And one night my wife and I were out at a restaurant, and I was leaning on my face like this, or on my neck, and I suddenly could feel this lump swelling up under my fingers. And I thought at first that it was just some sort of physical hallucination, until I looked at my wife, and she had just gone white. She reached across the table and took my wrist, and she said, darling, what's wrong? And I said, I don't know. And she thrust a glass of wine into my hands and said, drink this. And I drank it, and it calmed me down a little bit, but I could actually feel that this lump was there.

rnIt was hard and it was big and growing. And it was exactly like this lump that I had had in my neck when I was 14 that had taken years and years to get to the size of like an eggplant. But here it had come back in a matter of minutes. And I stumbled into the men's room, which, thank God, was empty, and I had to see it in the mirror, because I had to see what was happening to me. And there indeed again was this lump that I had had, which was of course cancerous when I was 14. And I realized at that moment that my body was expressing all of my repressed feelings and all of my anger and anxiety. Since I wasn't letting it out, since I wasn't able to speak about it, my body was speaking for me. And I understood in that moment, in that place, that awful little room, that I could die from it if I didn’t do something about it, that it was going to kill me. And it could have happened right there. And so I just took some deep breaths, and I said, this is not where I'm going to die, and this is not the end. And I'm going to do something about this. And it was that moment when I resolved to seriously get to work on this book. And the lump, of course, turned out to be a swollen gland. It went right down that same hour; it just went away. It just disappeared.

rnQuestion: Did drawing your parents humanize them for you?

rnDavid Small: Absolutely, yeah. No doubt about it. And that—you know, that humanization and that coming to understand somebody as a human being is about as good a kind of forgiveness as you can get, I think. I don't like my parents; I never will. I didn't cry at either of their funerals. I haven't missed them for five seconds. I didn't—you know, our characters were so at odds with one another right from the beginning. But I do understand them now as human beings, with the understanding of an adult. As a man, I can now—having seen them again and brought them back; having, you know, furnished the rooms and let the ghosts come in and act their little plays again—I've been able to see them and understand their impulses, their fears—their fears of having no money in the case of my mother. You know, that's an adult thing. Or hidden sexuality, sexual impulses that you don't want to bring out—that's an adult thing. Children don't understand this. You know, as a six-year-old—and my brother, we just—the two of us could not understand what was going on in our household. And I don't think any kid really can until they're adults. There are just certain things you can't talk about with kids. I just totally do not believe in this sort of Bart Simpson character who infects so much of our literature and film and TV stuff nowadays, these know-it-all kids who seem to understand the hypocrisy of the adult world so thoroughly and can talk about it with such articulateness. That's bunk. Kids are kids; they're innocents, they really are. For a long time, no matter what they see, no matter what they're exposed to, they can't get it until they have developed enough.

Recorded on November 18, 2009

Interviewed by Austin Allen