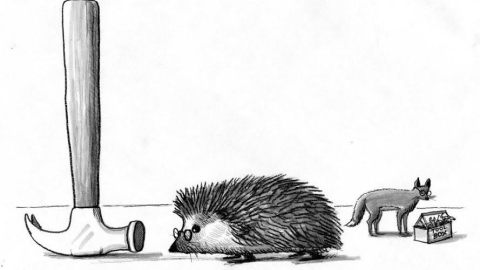

Beware The One Trick Hedgehog

There are two kinds of experts and we often don’t use them wisely. The differences between foxes and hedgehogs, and Newton and Darwin, can show when a diversified portfolio of experts is advisable. This year’s Nobel Prize committee in economics evidently agrees: It rewarded the apparently “opposing” theories of Eugene Fama (efficient markets) and Robert Shiller (animal spirits), which pit reason against passion.

Philip Tetlock did the relevant experiment, getting established experts to make 82,000 predictions about political and economic trends and tracking their accuracy. He found differences in thinking style that could predict who’d predict better. Tetlock classified experts using the aphorism “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

Hedgehogs think the world follows simple rules, and prefer a grand unified theory. Convinced they possess the One True Theory, they confidently and zealously defend it. This encourages a closed mindset which is more prone to confirmation bias (squeezing evidence into the theory and discounting what doesn’t fit).

Foxes believe the world is complex and distrust grand theories. They’re empirically driven, seek locally useful rules, and are open, cautious, eclectic thinkers tolerant of counter arguments. Unwedded to One True Theory they cope better with ambiguity, see the limits of their thinking tools, often qualify their opinions, and more readily adapt to new data.

Tetlock found that foxes fared better than hedgehogs, who barely beat “dart-throwing chimps.”

Despite that hedgehogs hogged the spotlight. The media love their certain sounding sound bites and flamboyant forecasts. Sadly, the most quoted were the worst predictors and increased confidence actually decreased accuracy.

Darwin’s greatest lesson applies: Fit to context is key. Hedgehog-experts are good in fields with stable behaviors and known rules. Otherwise, fox-experts are a better bet. This relates to how Newton differs from Darwin. Newton worked with unchanging behaviors. His laws can predict detailed outcomes in simple closed situations. But Darwin dealt with complex systems of changing parts and behaviors; he described the shape of open generative processes (note the cautious foxiness of that plural; “natural selection was the main but not the exclusive means” of evolution. These evolutionary processes have stable tendencies but less predictable specific outcomes.

The closer we get to humans and social sciences, the less Newton-like and hedgehoggy life gets. Economies, full of changing parts and innovative behaviors, need foxy thinking.

Aquinas famously feared “the man of a single book.” And we should be wary of experts with a single model. Models are hedgehog thinking incarnated. With assumptions built into their structure, they can create “model-risk.” Widespread use leads many to overlook the same issues. The dominance of Fama’s big idea possibly had this effect in the last financial crisis.

The more we rely on markets, the more important it is to use economic experts wisely. Market-loving hedgehogs tend to downplay the empirical problems of their beloved system. Fixed ideas are risky in a changing world; we’re predictably safer hearing also from market-realist foxes. So should we diversify or concentrate risks?

Illustration by Julia Suits, The New Yorker Cartoonist & author of The Extraordinary Catalog of Peculiar Inventions.