4 Million Babies and a Nobel Prize

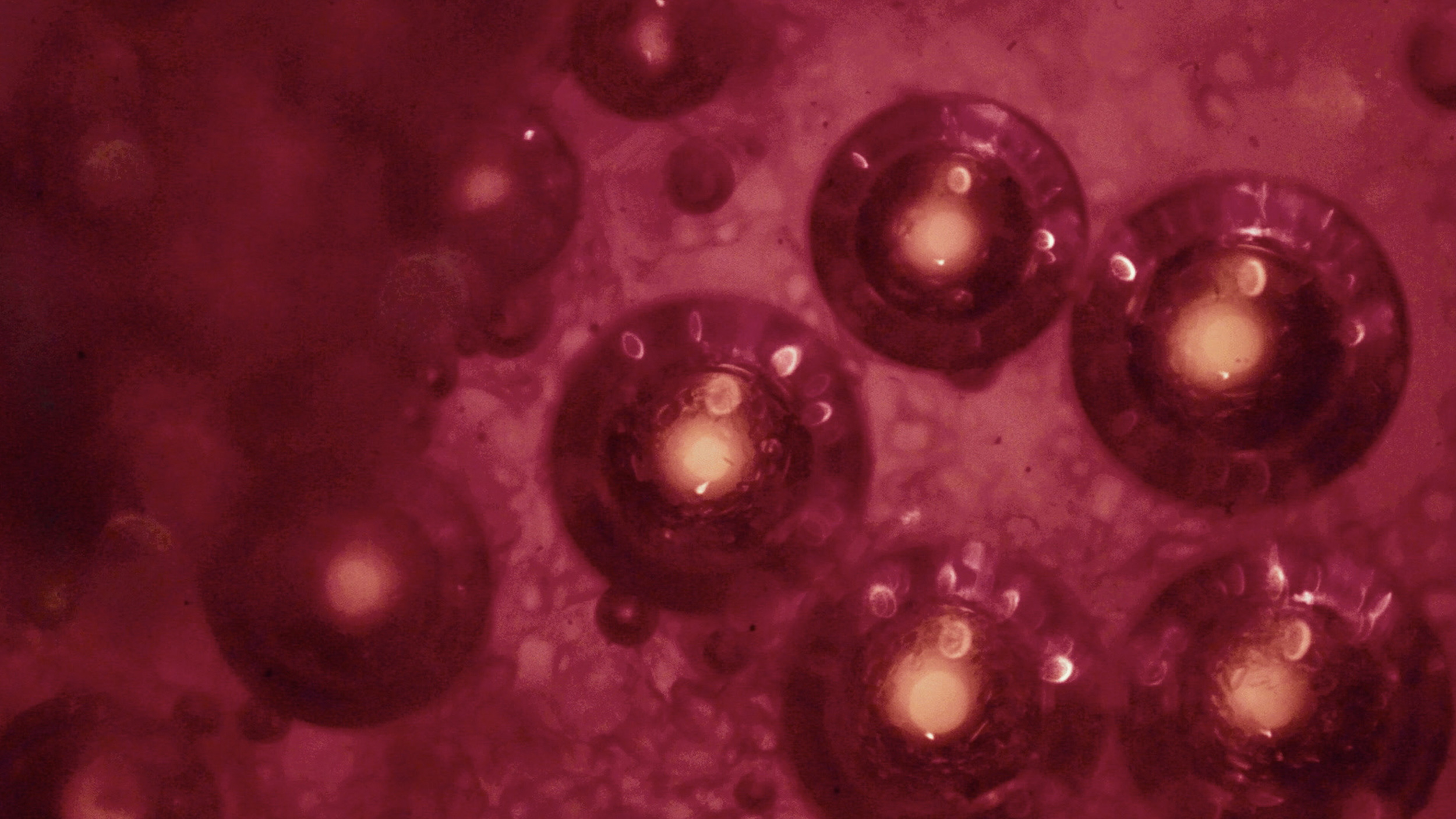

Last week, 85-year old obstretician Robert G. Edwards was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine for his breakthrough treatment of infertility commonly known as IVF (in-vitro fertilization). Edwards’s idea was revolutionary and went against everything most people considered normal, natural and even moral: a man and a woman did not need to have sex to produce a baby. Edwards claimed he could ‘make’ the baby in the laboratory. He created embryos by putting the eggs of the woman and the sperm of the man in a petri-dish where the eggs fertilized, and then he would put the resulting embryo in the woman’s body. In 1978, Edwards proudly announced the birth of the first ‘test-tube’ baby: Louise Brown.

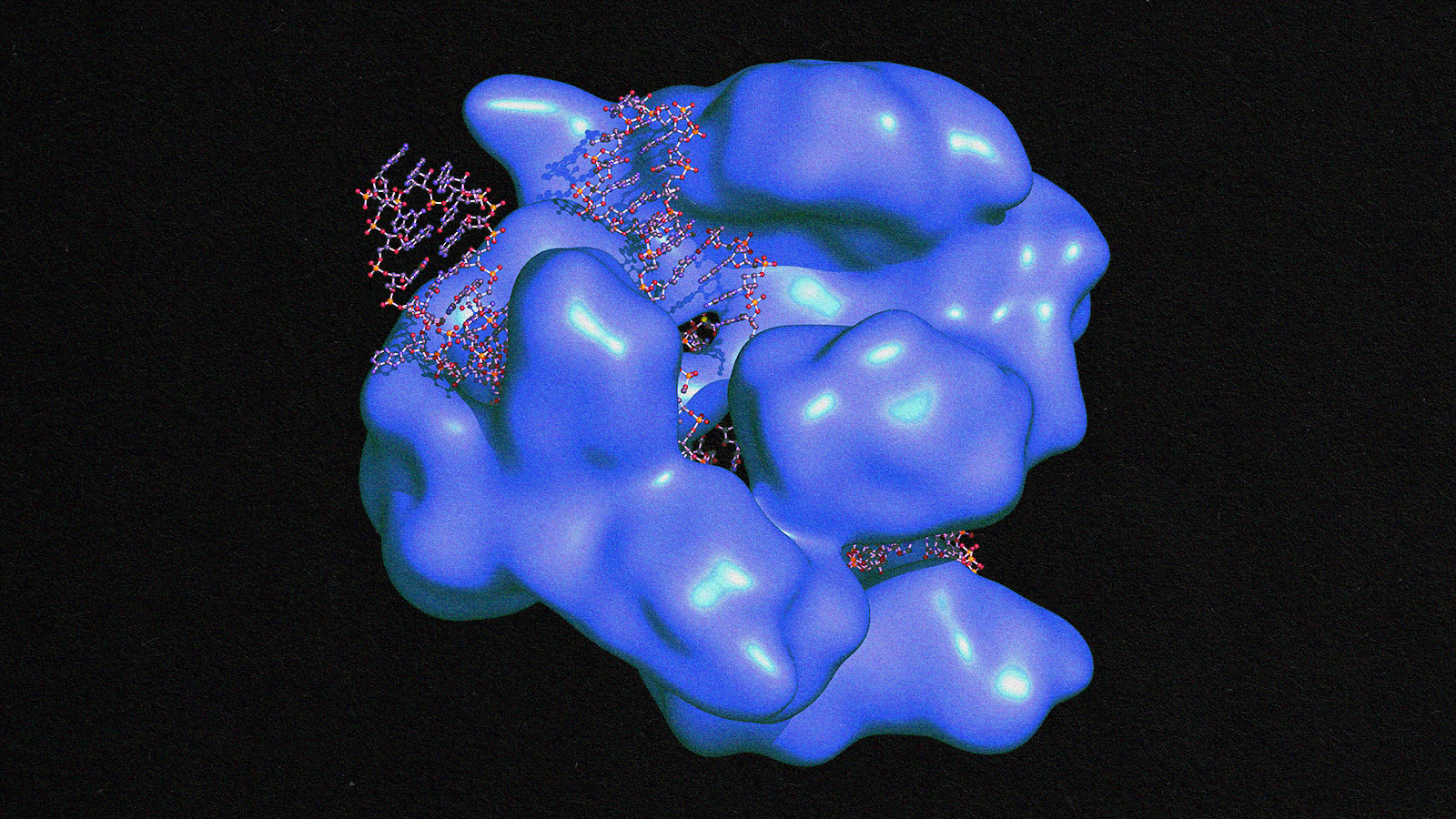

How far have we come in helping couples overcome fertility in the past three decades since Louise Brown? A long way. Over 4 million babies have been born using IVF, and by some estimates, approximately 3% of all live births in the developed world start with this procedure. The advances have been nothing short of spectacular. Take the example of male infertility. Male infertility is usually caused by inadequate sperm motility or poor ability of the sperm to move towards the egg. In a petri-dish, the problem is solved by an embryologist who physically injects the sperm in the egg using a process known as ICSI (intra cytoplasmic sperm injection). Another example is examining the genes of the embryo at conception using PGD (preimplantation genetic diagnosis), which couples with a history of debilitating illnesses in their family can use to detect unhealthy embryos before they are implanted in the body.

Genetic analysis of embryos is as controversial as IVF was when Dr. Edwards first proclaimed success in the procedure. Many conservative bioethicists fear that the ability to analyze and eventually engineer genes in embryos means we’ll begin not just creating them in the lab, but also designing them, choosing genes for intelligence, memory, and other enhancements parents believe will benefit their children in life. But the Catholic Church, conservative journalists and prominent scientists had the same reservations about IVF. Thirty-two years later, we awarded Edwards the Nobel Prize. If history is anything to go by, we can be certain that selecting enhancements for our children will one day be acceptable and completely normal. Not only is the science proceeding in that direction, but popular opinion tends to slowly but surely change to accept enhancements that prevent illnesses and improve people’s lives (although controls must always be put in place to prevent abuse).

Ayesha and Parag Khanna explore human-technology co-evolution and its implications for society, business and politics at The Hybrid Reality Institute.