The psychiatrist who treated syphilis with malaria — and won a Nobel Prize

- Austrian psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg won the 1927 Nobel Prize in medicine for treating late-stage syphilis by infecting patients with malaria.

- Malaria would trigger extremely high fevers that killed off the syphilis-causing bacteria in the body. Doctors could then treat malaria with quinine.

- The method was lauded for providing an effective solution to what was then a prevalent, terrible, and incurable disease. But it was rendered entirely obsolete within a few decades by the discovery of the antibiotic penicillin.

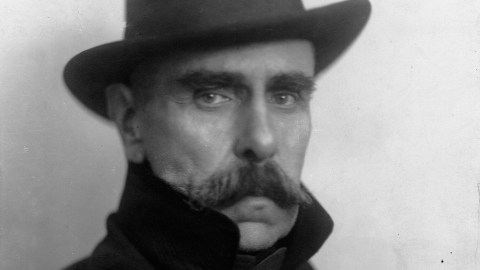

The Nobel Prize may be the greatest honor in all of science, ostensibly awarded to only the most groundbreaking and infallible work. But that hasn’t always been the case. Downright barbaric and subsequently disproved research has garnered the award in the past. At first glance, the 1927 prize in physiology or medicine, presented to Austrian psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg for treating late-stage syphilis by infecting patients with malaria, seems to be one of those questionable awards. But history tells a more nuanced tale.

When Wagner-Jauregg qualified as a medical doctor at the University of Vienna in 1880 at the age of 23, he originally aspired to practice internal medicine. Colleagues and mentors steered him to psychiatry instead. As he delved deeper into the discipline, he sought to turn psychiatry away from the psychoanalytic influence of Sigmund Freud. The brain is part of the body, he reasoned, so neuroses likely have a biological origin.

The “disease of the century”

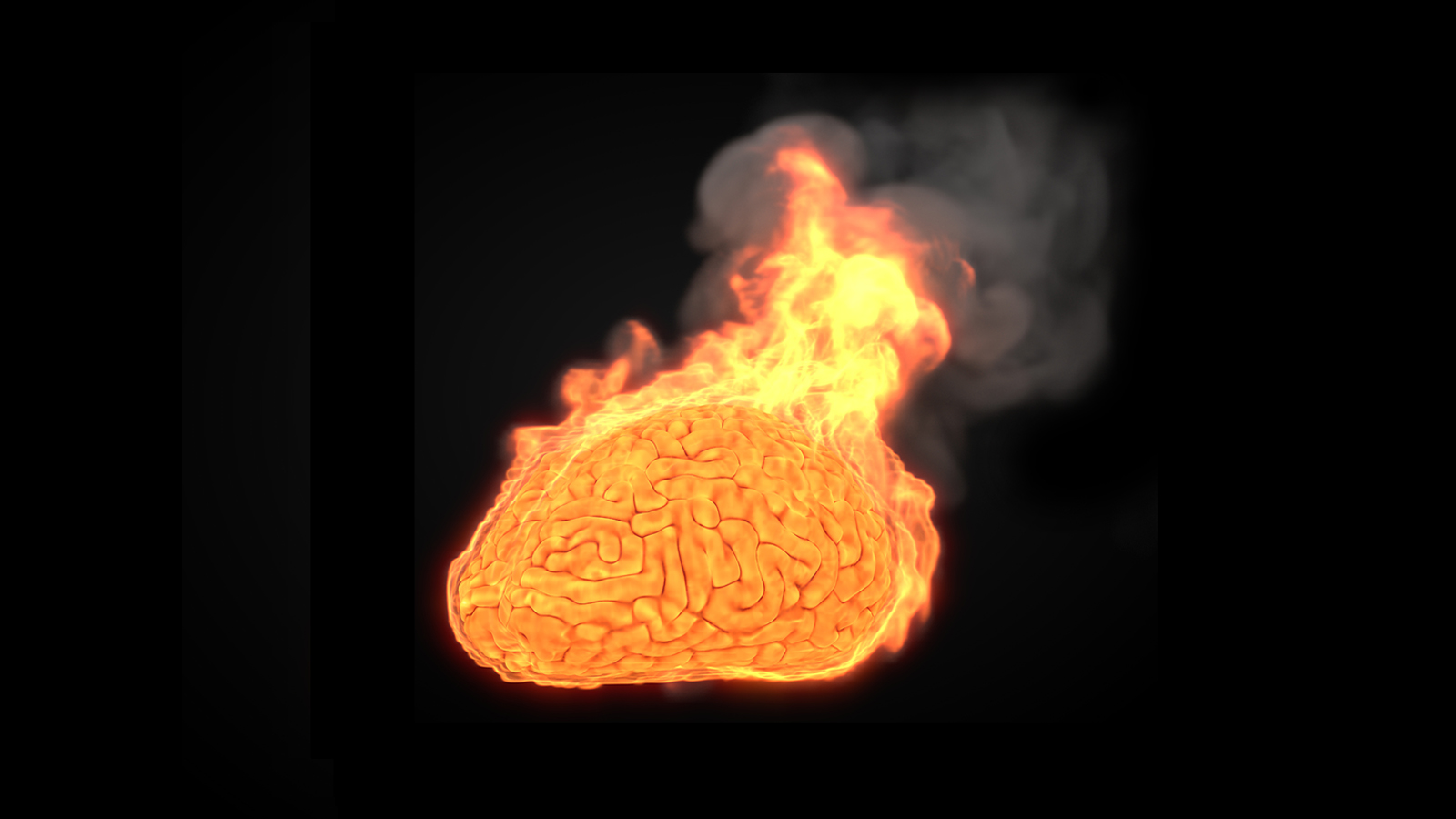

In 1883, as a young doctor in his first psychiatry position, Wagner-Jauregg witnessed a woman suffering from severe psychosis return to sanity after a brief bacterial infection triggered a high fever. This moment resonated with him. He kept it in the back of his mind over the ensuing years. Then, at some point, Wagner-Jauregg stumbled upon the obscure 1876 work of Russian psychiatrist Alexander Samoilovich Rosenblum, who infected psychotic patients with fever-causing diseases and reported cures in half of his cases.

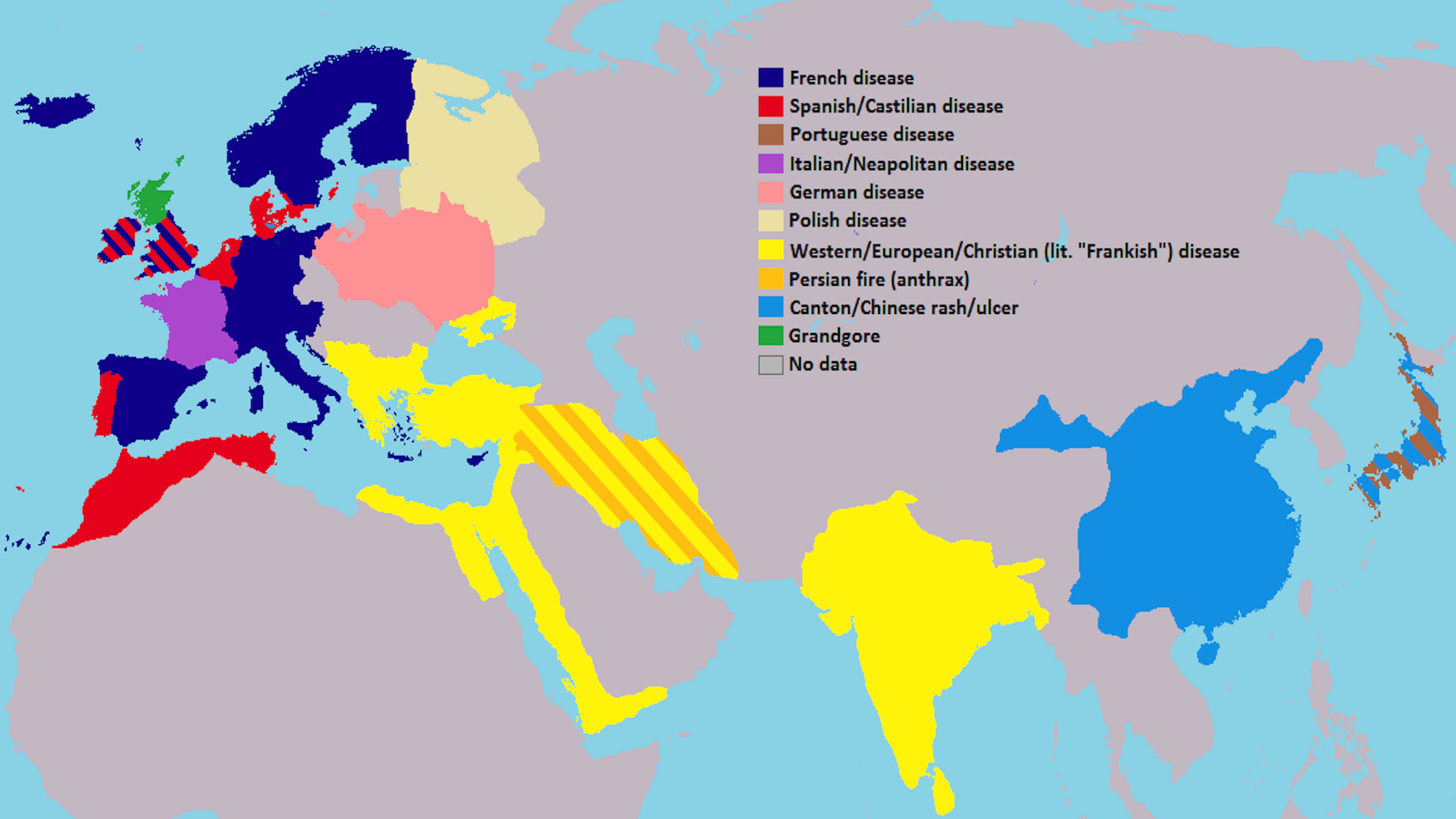

In 1917, more than three decades after observing a fever apparently cure psychosis, Wagner-Jauregg began a scientific study of the matter. He turned his attention to what was then known as the “disease of the century”: late-stage syphilis. At that time, syphilis, caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum, was mostly untreatable. The first modern antimicrobial, called Salvarsan, had just been discovered a few years earlier, but it was by no means as effective as the antibiotics we use today.

After years of a syphilis infection, the T. pallidum can weasel its way into the brain where it can wreak havoc, causing mental deterioration, personality changes, delusions, seizures, dementia, and eventually death. Syphilis infection in the brain quite literally drove people insane over a painful span of roughly three to five years, and then it invariably killed them. It did this at a terrifying rate, accounting for roughly 5% to 10% of all psychiatric admissions before 1945.

So while what Wagner-Jauregg did next might seem strange to us today, it made a lot of sense at the time. He took the blood of individuals infected with malaria caused by the parasite Plasmodium vivax — which is less virulent than the other major malarial threat, P. falciparum — and injected it into patients in asylums suffering from late-stage syphilis, oftentimes without their consent.

He did this procedure hundreds of times, triggering malarial fevers as high as 105°F (40.6°C) in his subjects before treating them with the antimalarial quinine. He hypothesized that the high fever would cure the syphilis — and he was right. Extremely high body temperatures killed the bacteria. Although many of his patients died, mostly of their syphilis but some of malaria, a quarter recovered. Late-stage syphilis of the brain was no longer a death sentence.

A “therapeutic noble deed”

At first, other scientists were skeptical when Wagner-Jauregg published his results. But the practice soon spread to institutions around the world. So many researchers attempted to replicate his results that by 1926 there were enough studies for a systematic review. It showed that treating late-stage syphilis with malaria resulted in full remission in 27.5% of cases, partial remission in 26.5%, and death or no change in 46%. Researchers and writers hailed the treatment as a “therapeutic noble deed,” a “distinct advance in treatment,” the “right way to treat a hopeless disease,” “unquestionably a method of value,” and the “best treatment available.”

And so it came to pass that, in 1927, Wagner-Jauregg was awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine. The malariotherapy that he pioneered, based on the earlier work of Rosenblum (whom he credited), would be used until the highly effective antibiotic penicillin became widespread by the middle of the 20th century.

The fact that antibiotics rendered malariotherapy so totally obsolete is a large reason why Wagner-Jauregg is so little known today. Another reason: In his old age, he became a staunch supporter of the Nazi movement and dabbled in eugenics research, though he reportedly became disenchanted with the party just before his death in 1940 at the age of 83, when party members advocated culling the mentally ill. Nevertheless, Wagner-Jauregg’s reputation was rightfully and forever tarnished, leaving us today to look back on his legacy of treating syphilis with malaria as a mere historical fascination, rather than the bold work of a caring physician.