Hitler’s SS: How do ordinary people become sociopathic Nazis?

- When it comes to understanding the evils of Nazism, historiography may be of more use to us than history.

- Historiography is the study of how the way historians interpret a particular subject changes over time as trends shift and new analytical methods develop.

- Immediately following the war, studies were based on interrogations with former Nazis. Later, these interrogations were replaced with the testimonies of Holocaust survivors.

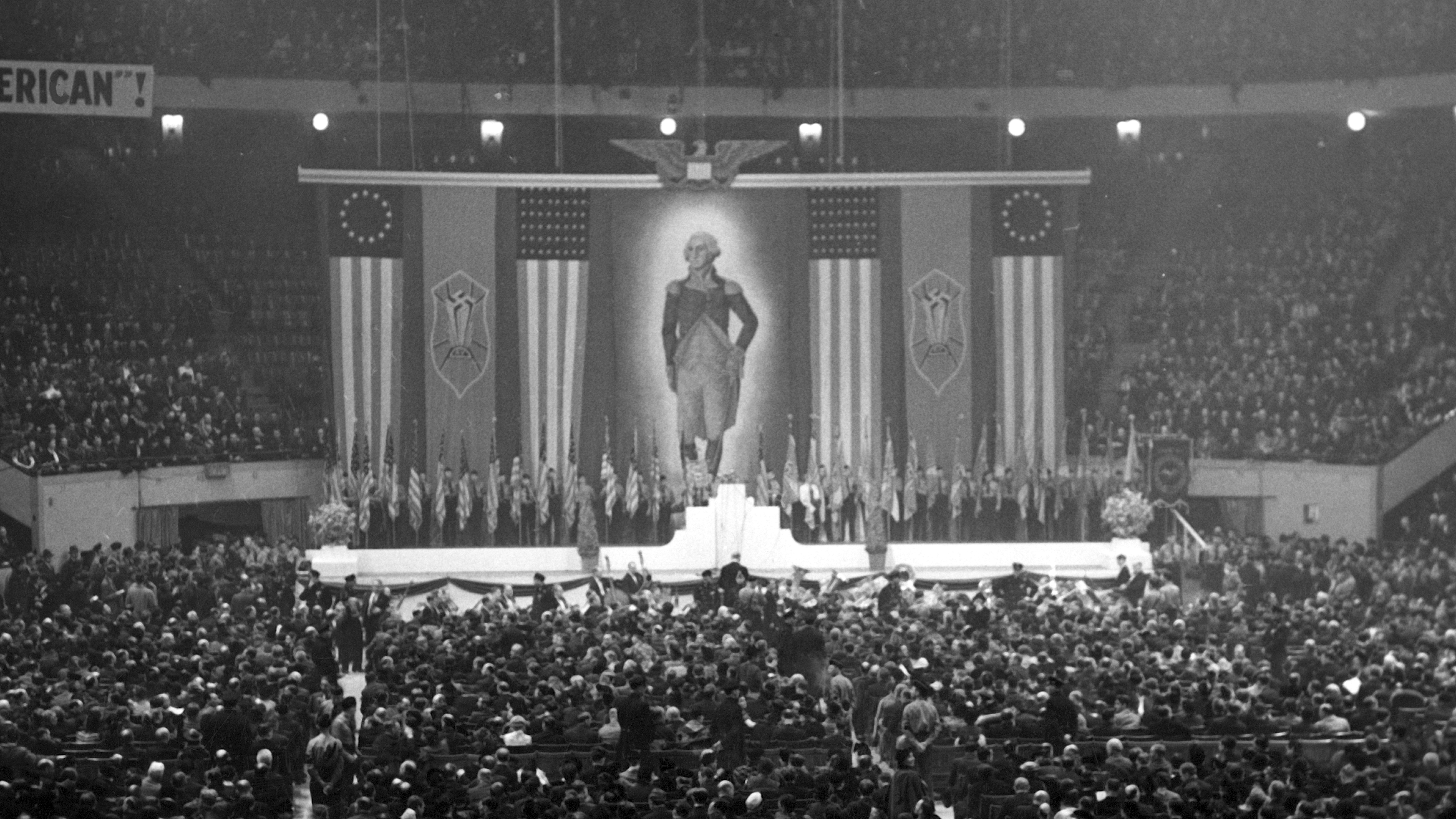

The driving factors behind the unprecedented violence witnessed during World War II have long eluded and divided scholars. One of the reasons for this is the fact that the organization of Nazi Germany’s Schutzstaffel or SS — the military order in charge of planning and executing the Holocaust — was not only kept secret from the wider world, but also from the citizenry of the Third Reich and even other compartments of Adolf Hitler’s own government.

Secrecy had played a role in the SS since its very formation. When Hitler rose to power within the Nazi party, he needed a force of armed bodyguards loyal only to him — a praetorian guard that could protect him against other figureheads threatening his authority, like Ernst Röhm. Röhm’s ranks were filled with military men, but Hitler chose people whose background resembled his own: lower-class laborers, butchers, and watchmakers who had previously had run-ins with the law.

SS men, German historian Heinz Höhne explains in his book The Order of the Death’s Head, were forbidden from taking German citizens to court, since doing so would risk giving the judicial system insight into the organization’s deliberately mysterious and confusing machinations. On orders of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler, no officer was to be deployed in their home region, and units were moved around every three months to prevent fraternization with the local community.

Of the SS, Hermann Göring — Reichstag president and commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe ± famously stated he had “no insight” and that “no outsider knew anything of Himmler’s organization.” It should, however, be noted that Göring made this statement during the post-war trials at Nuremberg, and that he may well have overstated his ignorance to feign innocence; Göring was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to death, but died by suicide instead.

While the inner workings of the SS are still unclear, the extent of its viciousness is not. While today’s estimates are much higher, Höhne’s 1966 book stated the Order of the Death’s Head was thought to have murdered between 4 and 5 million Jews; 2.5 million Poles; 520,000 Roma; 473,000 Russian prisoners of war; and 100,000 people suffering from incurable diseases. For over 75 years, scholars have tried to explain how such unfathomable barbarism could have taken place, but they have yet to succeed.

Understanding the SS

When it comes to understanding the motivations for Nazi violence, historiography might be of greater use to us than history. Historiography, simply put, is the study of history itself. Specifically, historiography looks at how the ways in which historians approach a particular subject or period change over time as academic trends shift and analytical methods develop. Every decade or so, scholars come up with different, often conflicting interpretations of the typical Nazi’s mindset and moral compass.

Initial studies of the SS were based on the shaky testimonies of persecuted Nazis. Immediately following the Second World War, former SS officers were hesitant to answer questions about their experience. They refused to accept personal responsibility for their involvement in the Holocaust and other war crimes on grounds that they had obeyed their superiors. Blame, consequently, was shifted to Nazi party leaders, most of whom had already been executed.

In the tolerant climate of West Germany, some members of the SS published autobiographies that conveniently absolved their authors from guilt. SS Untersturmführer Erich Kernmayr spoke of a “great frenzy” that had temporarily robbed Nazis of the ability to reason or empathize. Sturmbannführer Karl-Friedrich Brill followed Göring’s example, stating his own department, the Allgemeine SS, operated separately from the Waffen SS, who were really responsible.

The half-baked explanations these SS officers provided were soon replaced by more articulate and academically sophisticated accounts from concentration camp survivors and other victims of their terror. Buchenwald inmate and politics professor Eugene Kogon, author of The SS State, saw the SS as a “super organized master and slave system,” whose members were irrationally devoted to the will of a single person and pursued their plans “consistently step by step.”

Kogon argued that the SS was a homogenized entity, not only in terms of its operation but also the character of its members. SS officers, he wrote, were “maladjusted and frustrated… total social failures.” Psychologist Leo Alexander, who wrote part of the Nuremberg’s penal code, compared SS officers to common criminals. Rudolf Pechel, editor and resistance fighter, maintained you could recognize SS officers simply from the dull, lifeless look in their eyes.

Hannah Arendt’s banality of evil

These commentators presented the SS as a highly organized and hyper-functional institution that consisted of people with similar sociocultural and psychological backgrounds acting from the same primordial motivations. Starting in the 1950s, writers like Karl O. Paetel suggested that the reality had been more complex. He concluded SS units consisted of a variety of people — including intellectuals, idealists and common criminals — who rallied around the same cause for different reasons.

The image sketched by Paetel became reinforced by the release of previously classified SS files. These indicated the SS was not a well-oiled machine that turned maladjusted people into mindless killers. Nor did its members operate in complete isolation from the rest of the Third Reich. Instead, the SS seems to have been made up of people who had acted consciously and deliberately, sometimes resisting their superiors but always realizing principles that lay at the heart of life in Nazi Germany.

Some of the most comprehensive and enduring takes on SS violence were produced by the philosopher and Holocaust survivor Hannah Arendt. Her 1963 book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil depicted Third Reich governance as inefficient and anarchic, albeit by Hitler’s own design. In order to secure his place at the top of the pyramid, the Führer made it so that the flow of command down from him was anything except hierarchical, causing confusion and internal competition.

More arresting than the procedures of the Nazi state were the personalities of some of its key administrators, particularly the SS Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann. Instead of an outwardly “perverted or sadistic” murderer, Arendt found a “terrifyingly normal” bureaucrat. The juxtaposition of Eichmann’s extraordinary crimes with his seemingly unextraordinary character led the philosopher to coin her now-infamous phrase, “the banality of evil.”

Eichmann, it appeared, was someone who had participated in Nazi atrocities not for ideological reasons, but to advance his bureaucratic career. This meant that his misdeeds were rooted primarily in his lack of self-reflection. “Evil,” Eichmann in Jerusalem reads, “comes from a failure to think. It defies thought for as soon as thought tries to engage itself with evil… it is frustrated because it finds nothing there. That is the banality of evil.”

Ordinary men vs. willing executioners

At the time of publication, Eichmann on Trial drew criticism from scholars who were both unable and unwilling to understand how someone could actively participate in racial genocide without intentions that could be considered evil in the conventional sense of the word. Sifting through audiotapes of conversations between Eichmann and Nazi journalist William Sassen, historians eventually learned Eichmann was far more radical in his devotion to Nazi ideology than Arendt had originally believed.

Namely, Eichmann told Sassen there were two sides to him, the cautious bureaucrat and the “fanatical warrior fighting for the freedom of my blood.” Others, like the novelist Mary McCarthy, reconciled their own interpretation inside Arendt’s theoretical framework. “[I]t seems to me that what you are saying is that Eichmann lacks an inherent human quality,” McCarthy commented, “the capacity for thought, consciousness — conscience. But then isn’t he a monster simply?”

Arendt’s work made another large impact on the historiography of Nazism insofar as it drove historians to look at the SS on a person-by-person basis as opposed to a sociological basis. Later studies shifted from high-ranking ideologues to ordinary Germans without political aspirations. Christopher Browning found a particularly promising research topic in the form of Reserve Police Battalion 101, a paramilitary organization under SS leadership that carried out mass executions in Poland.

The Police Battalion was unique among Nazi paramilitary groups because it consisted mostly of volunteers, less than one-fourth of which were members of the Nazi party. While these volunteers were given the choice whether or not to participate in the ongoing genocide, more than 80% of them agreed to follow orders. Browning’s book, Ordinary Men, influenced by the Milgram experiment, argues that the volunteers did so primarily out of pressure to conform to expectations from their peers.

Browning’s claim proved to be as controversial as Arendt’s. Opposition to Ordinary Men soon formed around the author, and government studies professor Jonah Goldhagen — whose rebuttal to Browning in a book titled Hitler’s Willing Executioners — stresses that the inhumanity displayed during the Holocaust is evident to any rational human confronted with it, and should not become lost in the overly complicated webs of academic or theoretical inquiry.

“Antisemitism moved many thousands of ‘ordinary’ Germans,” reads Goldhagen’s conclusion, “to slaughter Jews. Not economic hardship, not the coercive means of a totalitarian state, not social psychological pressure, not invariable psychological propensities, but ideas about Jews that were pervasive in Germany, and had been for decades, induced ordinary Germans to kill unarmed, defenseless Jewish men, women, and children by the thousands, systematically and without pity.”