At the Dawn of American Literature: A Hurricane

Cuba. 1527. “All hands labored severely under a heavy fall of water that entire day and until dark on Sunday. By then the rain and the tempest had stepped up until there was as much agitation in the town as at sea. All the houses and churches went down. We had to walk seven or eight together, locking arms, to keep from being blown away. Walking in the woods gave us as much fear as the tumbling houses, for the trees were falling too, and could have killed us. We wandered all night in this raging tempest without finding any place we could linger as long as half an hour in safety. Particularly from midnight on, we heard a great roaring and the sound of many voices, of little bells, also flutes, tambourines and other instruments, most of which lasted till morning, when the storm ceased.”

Thus Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, writing about his expedition to North America, and providing the earliest description in literature of a hurricane. (The translator here is Cyclone (yes, really) Covey.)

Cabeza de Vaca had a terrible/wonderful fate: Disasters winnowed his expedition to Florida down to himself and three other men, who then walked 6,000 miles, from present-day Florida to Arizona, over the next eight years, meeting and describing people, animals and natural wonders never before known to the European mind. In an age of conquerors he only survived by becoming a kind of anthropologist and a kind of healer, tolerated and trusted by the people he met because he could cure sickness, bring news and engage in trade.

His book, published in 1542, is the great-grandfather of Moby Dick and a lot of Cormac McCarthy’s novels and a great many others as well. It inaugurated a uniquely American literary form: The story whose main antagonists, and most significant characters, are not other people but deserts and seas, storms and floods, heat and cold. It’s the kind of story where the greatest tests, and greatest knowledge, come not from other humans, but from Nature.

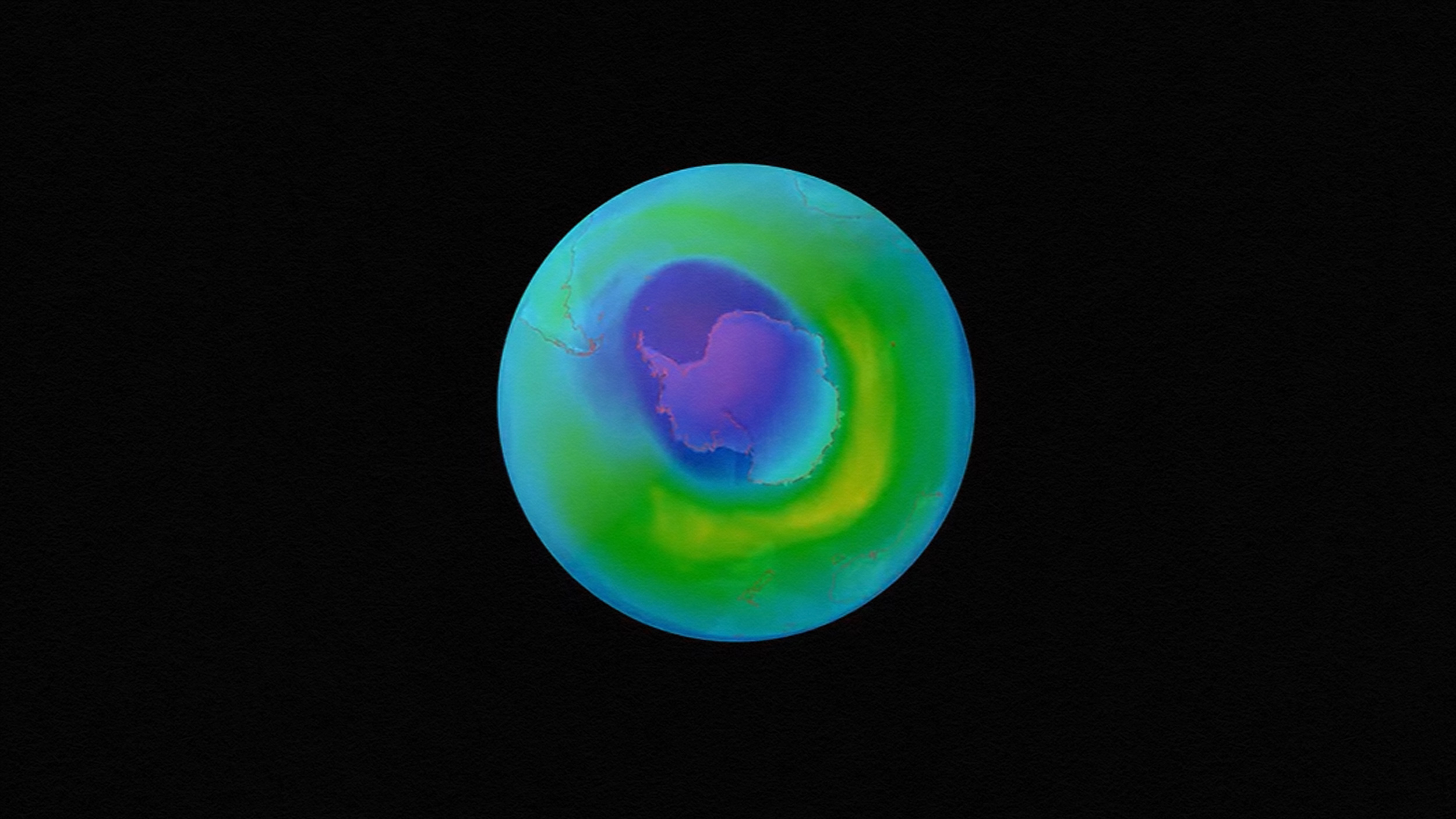

So as Irene passes on from where I sit, electrified, wi-fi’d, informed by satellite imagery and protected by a lot of brave and dedicated people who are battling nature in various ways, here’s to Cabeza de Vaca, who survived a bigger storm with only his ingenuity, determination and a few locked arms. And who from such experiences inaugurated a particularly American way of representing the mind.

Illustration: Statue of Cabeza de Vaca, via Wikimedia.