Much Ado About Drug-Testing Shakespeare’s Corpse

“Blessed be the man that spares these stones, / And cursed be he who moves my bones,” Shakespeare’s gravestone famously proclaims. Anthropologist Francis Thackeray, the man currently petitioning the Anglican Church to exhume the Bard, insists that he’s not disobeying this warning. He just wants to do a few laser scans and sample the corpse’s teeth, not “move any of the bones.” Besides, the research is for a worthy cause: who wouldn’t want to find out if the world’s greatest playwright smoked ganja?

I can’t decide what I like most about this story: the fact that a man named Thackeray is trying to dig up Shakespeare, the fact that he’s investigating whether Shakespeare was a pothead, or the fact that the tombstone curse has actually spooked him a little. It all sounds like the dream I had the night I studied for my Comp Lit final while watching Scooby-Doo.

Thackeray’s fellow anthropologists are skeptical that the project would yield any solid scientific data. Don’t hold your breath for any literary insights, either. It doesn’t matter whether Shakespeare was smoking weed, drinking mead, or playing hopscotch while he wrote King Lear, because no one else has ever written King Lear—or anything like it—while doing the same things. Whatever Shakespeare’s secret was, a drug test isn’t going to turn it up.

A fairer question is, what has Thackeray been smoking? He made his name over a decade ago by digging up suspicious clay pipes in the playwright’s garden, but he’s not leaving it at that—that was evidence, but he swears he can find proof, man. The poor guy is destined to be a minor comic character in Shakespeare biographies for years to come.

Accordingly, he deserves our sympathy, and even our affection. His quest makes me think of a passage from Mary Ruefle’s wonderful poem “Sentimental Education”:

Please pray for William Shakespeare,

who does not know how much we love him, miss him, and think of him.

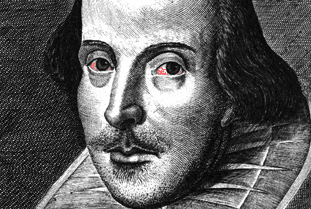

This moving tribute, which Ruefle slips into a litany of grade-school crushes, reminds us that “Bardolatry” is a special kind of unrequited love. We want to know everything about Shakespeare—what was he like in person? what would he think of us? would he get high with us?—but he never seems to talk. He disappeared totally into his work, then disappeared into his grave and asked us not to bother him.

Still we keep at it, poring over his commas, his DNA, for clues. Some Shakespeare scholars end up going crazy. Others find his silence so painful that they try to reject him, claiming that he was really Edward de Vere or Christopher Marlowe all along. Damn it, Bill, you’re not the man we thought you were! Even the sanest researchers finally shrug in defeat, admitting that we can simply never know enough.

And that, of course, is the curse. If he opens Shakespeare’s tomb, Thackeray won’t be haunted by witches or hit by a bus—he’ll just get his heart broken, no matter what he manages to unearth. The playwright will remain as serenely inscrutable as ever, but the scientist will never be able to rest in peace.