Rising Up: Leonard Baskin’s Portrait Gallery

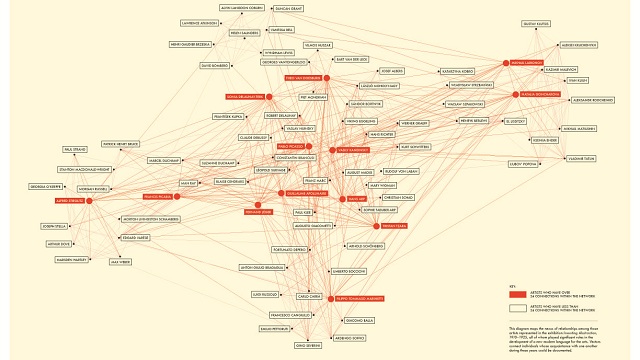

When Daedalus crafted wings of feathers and wax for his son Icarus, he included the warning to not fly too close to the sun. As anyone who knows Greek mythology remembers, Icarus ignored the warning and plunged into the sea to his death. Artist Leonard Baskin never forgot the story of Icarus, which merged two of his greatest interests—men and birds—and created a woodcut of the fallen son in an egg-like oval, as if the tragic boy were truly born a bird. When Alfred Appel, Jr., a literary scholar as well as author on modern art and jazz, came across Baskin’s literary-tinged art in the 1960s, he fell, too—in love. Leonard Baskin: Art from the Gift of Alfred Appel, Jr., which runs at the Delaware Art Museum through January 9, 2011, tells the story of that collector’s love affair with Baskin’s art and Baskin’s love affair with the great artists in words and images that inspired his paintings and sculptures.

“Our human frame, our gutted mansion, our enveloping sack of beef and ash is yet a glory,” Baskin remarked years ago. “The human figure is the image of all men and of one man. It contains all and it can express all.” Just when other artists in the 1950s and 1960s abandoned the human figure in their art, Baskin placed it front and center. This humanism fascinated the humanist scholar Appel , who became friends with Baskin in the process of collecting Baskin’s art over the years. Icarus holds a special place in Baskin’s oeuvre because it not only presents the human unashamedly, but also because it presents a figure that aspired to greater heights and paid a price for that ambition. Many of the other figures in Baskin’s gallery of heroes also realized a dear cost for their principles.

William Blake, the misunderstood visionary painter-poet of the Romantic era, finds himself surrounded by two of the “Youthful Ancients,” younger artists devoted to keeping Blake’s ideas alive, in one suite of wood engravings by Baskin. Herman Melville, the 19th century novelist who died in poverty only to be resurrected in the 20th century as the author of the Great American Novel Moby-Dick, finds a place in Baskin’s list through illustrations for Melville’s short story, “Bartleby, the Scrivener.” Bartelby becomes a stand-in for Melville himself, who preferred not to follow the conventions of his time and paid the price necessary for posthumous glory. Works honoring fellow artists Rembrandt, Chaim Soutine, Goya, Gustave Courbet, Caspar David Friedrich, and Odilon Redon and even composer Gustav Mahler all continue this pattern of artists who suffered for their artistic principles in life but are recognized for their greatness today.

Baskin gives special prominence to a particular fallen hero of American art, Thomas Eakins. The exhibition features several portraits Baskin did of Eakins, some based on photographs of the artist and some inventions of Baskin’s imagination. These portraits show a deep understanding of Eakins the artist and his torment over misunderstandings of his goals, which led to his losing his teaching job in scandal and working thereafter on the fringes of the American art scene until nearly the end of his life, when a brief respite of recognition eased his final days. One portrait by Baskin of Eakins done in copper pays homage to Eakins’ bronze medallions, Spinning and Knitting, which Eakins hoped would tap into the nostalgia of his age but never found a contemporary audience. Baskin portrays Eakins at different vantage points of his career—1870, 1890, and even 1915, the year before Eakins’ death—to collectively present a timeline of suffering and endurance. The “gutted mansion” of the human figure stands tall and strong against even the cruelest winds of indifference in these portraits paying honor to the artists of the past.

Leonard Baskin: Art from the Gift of Alfred Appel, Jr. demonstrates the power of an artist to cross the boundaries of his art and find a common element with other creative minds, even the creative mind of the critic, in the case of Dr. Appel. Dr. Appel’s commitment to collecting Baskin’s human-centered art in a time when dehumanized art was trendy stands as a testament to his commitment to the ideals of humanism in the arts. Dr. Appel’s generosity in giving these works to the public as a gift stands as an even greater testimony to his belief that these works contain ideas and ideals that each generation needs to experience and internalize. Each generation knows its own Icarus and its own story of a fall from great heights. The art of Leonard Baskin reminds us that, like Lazarus (another of Baskin’s favorite figures of ancient story), those who fall will rise again.

[Image: Leonard Baskin (1922-2000). Icarus, 1967. Color woodcut on paper, 32 x 21 ¾ inches. Gift of Alfred Appel, Jr., 2009. © Estate of Leonard Baskin, Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York.]

[Many thanks to the Delaware Art Museum for providing me with the image above and press materials for Leonard Baskin: Art from the Gift of Alfred Appel, Jr., which runs through January 9, 2011.]