Sorting Books and Digitizing Thought

This holiday season, Hybrid Reality is preparing for the next digital decade by cleaning out the attic and donating books to charity—an interesting opportunity to reflect on the future of authorship, knowledge, and access to information.

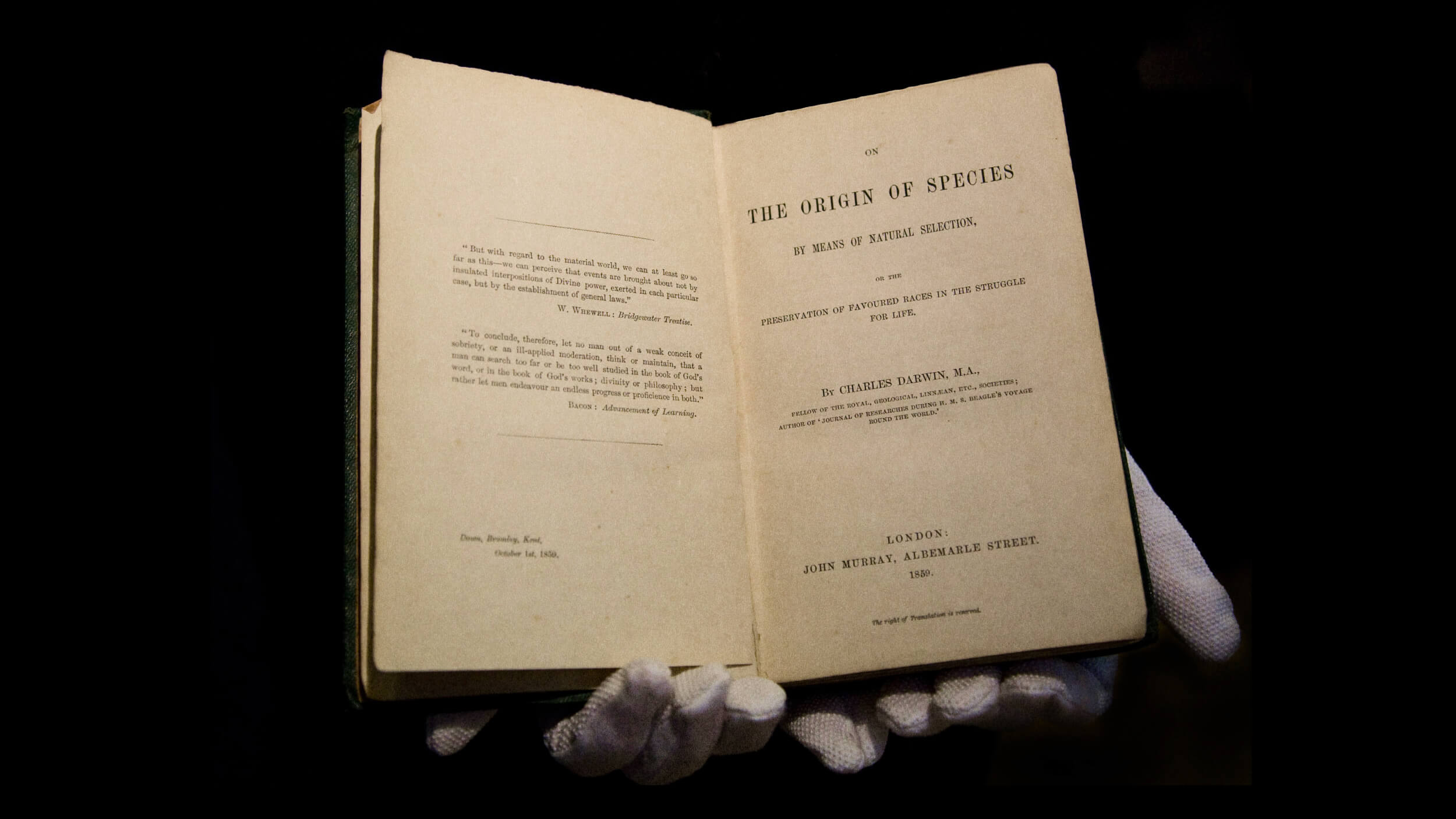

Very little now remains on our shelves, yet it’s worth noting that we have only kept the oldest books in our collection: rare manuscripts, classical philosophy, religious texts. Some of these are available online, but not only do they have sentimental value, holding them in your hand puts you in the right frame of mind to appreciate and absorb their teachings. They are timeless in a different way than digital content now is as well.

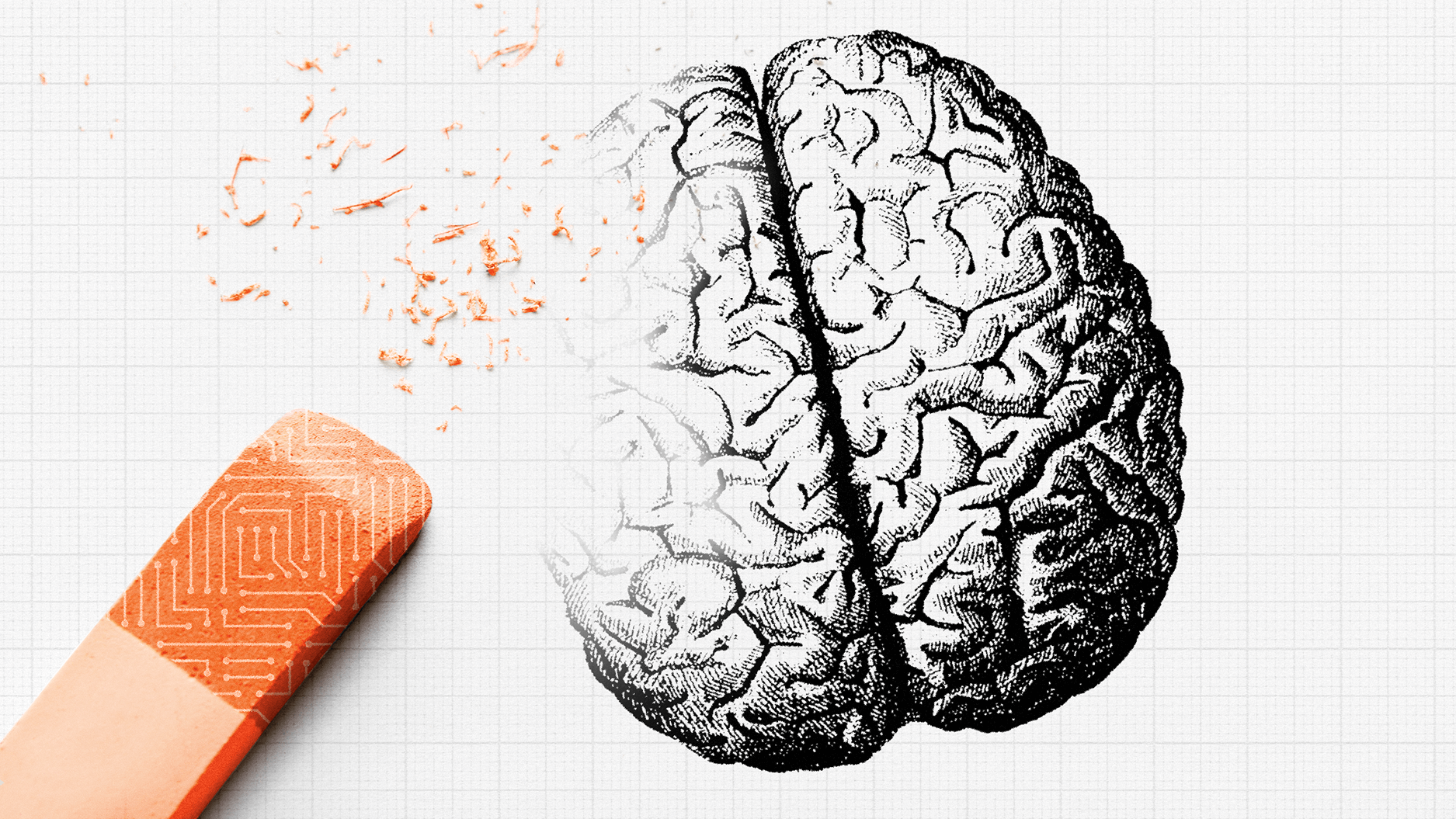

As we lose access to the bound volumes in which we scribbled comments, annotations, critiques and other markings, it becomes more difficult to find the boundary between content production, consumption, and recycling. It is so easy to read several books at once from the Kindle or IPad bookshelf as opposed to the real thing—plus digital readers are amazingly portable. This is particularly important for Generation-Z, whose virtual libraries will be far larger than their physical ones, whose education system is already riddled with cut-and-paste plagiarism, and whose minds are so constantly bombarded with information that they can hardly be blamed for not knowing what they learned where and from whom.

Commercial imperatives are driving this accelerated blurring of content boundaries. Barnes & Noble stores are closing while Kindle sales are rising—and this despite the settlement that has seen Amazon allow publishers and authors to set their own price for books, usually at parity with the hardcover despite the decreased production costs of digital content. Barnes & Noble is trying to adapt to the trend, heavily marketing its own version of the Kindle or IPad—the “Nook”—and even selling it front-and-center on the lobby tables of bookstores instead of books themselves. So here is where we stand: Customers are going to bookstores to buy digital book readers.

Of course, it is still premature to herald the complete demise of the bookstore. Libraries have closed across America due to lacking public funding, not due to lack of demand from the public who seek spaces to browse books, surf the Internet, and convene with fellow citizens—all free of charge. Some bookstore chains have tried similar strategies, offering far more magazine selections, Starbucks cafes within, and free WiFi. Our visceral needs for caffeine and communing haven’t dissolved into the ether as quickly as the content we consume.

But this communing is now happening on an infinitely broader scale. The growing access to a nearly universal body of information raises the tantalizing prospect not only of having access to, but being constantly plugged into, a global knowledge vault with the Jesuit scholar Teilhard de Chardin dubbed the “Noosphere” a half-century ago. Through digitized content we can absorb more information faster, and more rapidly combine it with other sources to produce new knowledge. It is becoming harder and harder to disentangle the original source of ideas in cyberspace—we don’t yet have RFID tags for ideas—but that is a small price to pay to access, or re-access, much of what we may have forgotten over the years since school without the dustiness of going into the attic.

Ayesha and Parag Khanna explore human-technology co-evolution and its implications for society, business and politics at The Hybrid Reality Institute.