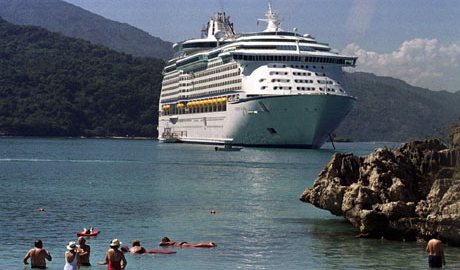

The Beaches of Labadee

Royal Caribbean International is continuing to dock its luxury cruise ships on the beaches near Labadee in Haiti, near the epicenter of the earthquake. Some passengers are queasy about this. As one put it: “I just can’t see myself sunning on the beach, playing in the water, eating a barbecue, and enjoying a cocktail while there are tens of thousands of dead people being piled up on the streets” only 60 miles away in Port-au-Prince. But these feelings raise an important question about the human mind: At what distance from misery can you see yourself having a good time? Is it 100 miles? Or 250, or 1,000?

The company has good and rational reasons for keeping the luxury beaches open: It’s donating all the proceeds from the Labadee stops to earthquake relief, keeping 230 Haitians employed, and transporting aid as well as vacationers. (The Independence of the Seas delivered 40 pallets of food supplies on January 15, for example.) Royal Caribbean is working within the moral and political system that we’ve built. But the psychological question–why is it built this way?–is important.

If you’re reading this, you’re connected to the Internet in a world where (as Noam Chomsky likes to say) the majority of people have never made a phone call. You and I and the world’s other billion richest people have a stateroom on a metaphorical luxury liner. So the management of our empathy is a psychological question with great practical and political consequences: If we felt less moved by this emotion, some 2.3 million earthquake victims wouldn’t be getting food aid this week. But if we felt more, the sums we’ve spent on Avatar and Bugattis and competitive eating contests would have gone instead to help strangers who, instead, died of poverty.

Bugattis are famous in debates about this, because of this thought experiment proposed by the philosopher Peter Unger. Unger imagines a man who has to choose between saving a child’s life and saving his favorite possession (and de facto retirement fund), a classic Bugatti. Most people think the guy’s a creep if he saves the car, but, Unger suggests, if you spent $200 on fun last year instead of sending it to Unicef, you’re in the same moral position. Hence, argues Peter Singer, people with surplus income should be giving it all to the poor.

That’s not the world we live in. Where Singer would have people use ethical principles and reason, their actual behavior is governed by feelings of empathy. And empathy comes and goes. It’s not consistent, reliable or well understood.

One thing we do know: Human beings didn’t invent empathy, as the primatologist Frans de Waal pointed out in his most recent book. Even mice feel distress when they see another mouse in pain, and many animals spontaneously help others. (De Waal and I recently had a conversation about all this, which is here.) But empathy in animals is limited to friends and family (de Waal says those mice don’t feel distressed when they don’t know the mouse in pain; then too elephants only react to warning calls from elephants they’ve met). Among non-human creatures, fellow-feeling and helpful acts are universally reserved for “us” and withheld from strangers.

Human beings, though, can feel akin to any other person (for that matter, with animals and even with machines). Conversely, we can decide that even a sister or daughter is unworthy of fellow-feeling, and make ourselves indifferent to their pain.

Then too, we belong to many different kinds of groups, which only partly overlap, so our motives to help, or not help, are varied. This is why some people explain they want to help earthquake victims because “we’re parents too” while others are moved more by a feeling of religious identity (or a feeling of explicitly non-religious identity). While for others it’s about knowing the place and its people.

All this suggests that human beings are constantly managing their own feelings of empathy for others. That means, on the one hand, that we can decide to do more next week than last week. It also means, of course, that we can decide to do less. For the moment, anyway, as the psychology isn’t completely explained, it’s impossible to say, scientifically, just how far the jetskis need to stay from the corpses.