The wicked souls of utilitarians

Are utilitarians bad people? Probably not. But is there nevertheless something wrong with them? This study, summarized in The Economist, seems to be getting around, and seems to suggest as much.

A utilitarian, for example, might approve of the occasional torture of suspected terrorists—for the greater happiness of everyone else, you understand. That type of observation has led Daniel Bartels at Columbia University and David Pizarro at Cornell to ask what sort of people actually do have a utilitarian outlook on life. Their answers, just published in Cognition, are not comfortable.

[…]

Dr Bartels and Dr Pizarro knew from previous research that around 90% of people refuse the utilitarian act of killing one individual to save five. What no one had previously inquired about, though, was the nature of the remaining 10%.

To find out, the two researchers gave 208 undergraduates a battery of trolleyological tests and measured, on a four-point scale, how utilitarian their responses were.

[…]

Dr Bartels and Dr Pizarro then correlated the results from the trolleyology with those from the personality tests. They found a strong link between utilitarian answers to moral dilemmas (push the fat guy off the bridge) and personalities that were psychopathic, Machiavellian or tended to view life as meaningless. Utilitarians, this suggests, may add to the sum of human happiness, but they are not very happy people themselves.

If you think utilitarianism is the correct theory, you might infer, as does Roger McShane, my colleague at Democracy in America that “If we really want the greatest happiness of the greatest number, we should be electing psychopathic, Machiavellian misanthropes.”

Set aside the truth or falsity of utilitarianism. This is a mistake. Utilitarianism is a theory of the good (happiness, pleasure, what have you) and of the right (do that which brings about the most good). So, according to utilitarianism, one should accept utilitarianism only if accepting utilitarianism leads one to do more good than accepting one of the many alternatives to utilitarianism. As one of philosophy’s greatest utilitarian theorists (and an early president of the Cambridge Moral Sciences Club) taught:

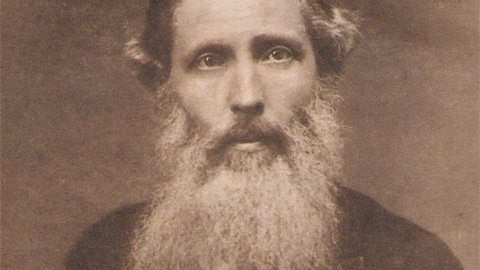

[A] Utilitarian may reasonably desire, on Utilitarian principles, that some of his conclusions should be rejected by mankind generally; or even that the vulgar should keep aloof from his system as a whole, in so far as the inevitable indefiniteness and complexity of its calculations render it likely to lead to bad results in their hands.

Henry Sidgwick here is holding on to the possibility that the influence of utilitarianism may be benign if limited to a technocratic elite, a convenient opinion for the colonial overseers of the British Empire, who knew they had to break a few eggs to bring civilized omelets to the savage races. But Sidgwick’s point is general: a utilitarian may desire, on utilitarian principles, that all of his conclusions should be rejected by mankind entirely. That utilitarianism as a creed leads to good utilitarian results is an empirical matter impossible to settle through philosophical argument.

Since it seems implausible that we are best off governed by Machiavellian psychopaths, I take the findings of Bartels and Pizarro–that those attracted to utilitarianism tend toward the psychopathic and Machiavellian–as prima facie evidence that utilitarianism is “self-effacing,” that it recommends its own rejection. This is a study about how, if you are a utilitarian, you should probably do the world some good and shut up about what you really think is best.