Was Vincent Van Gogh Murdered?

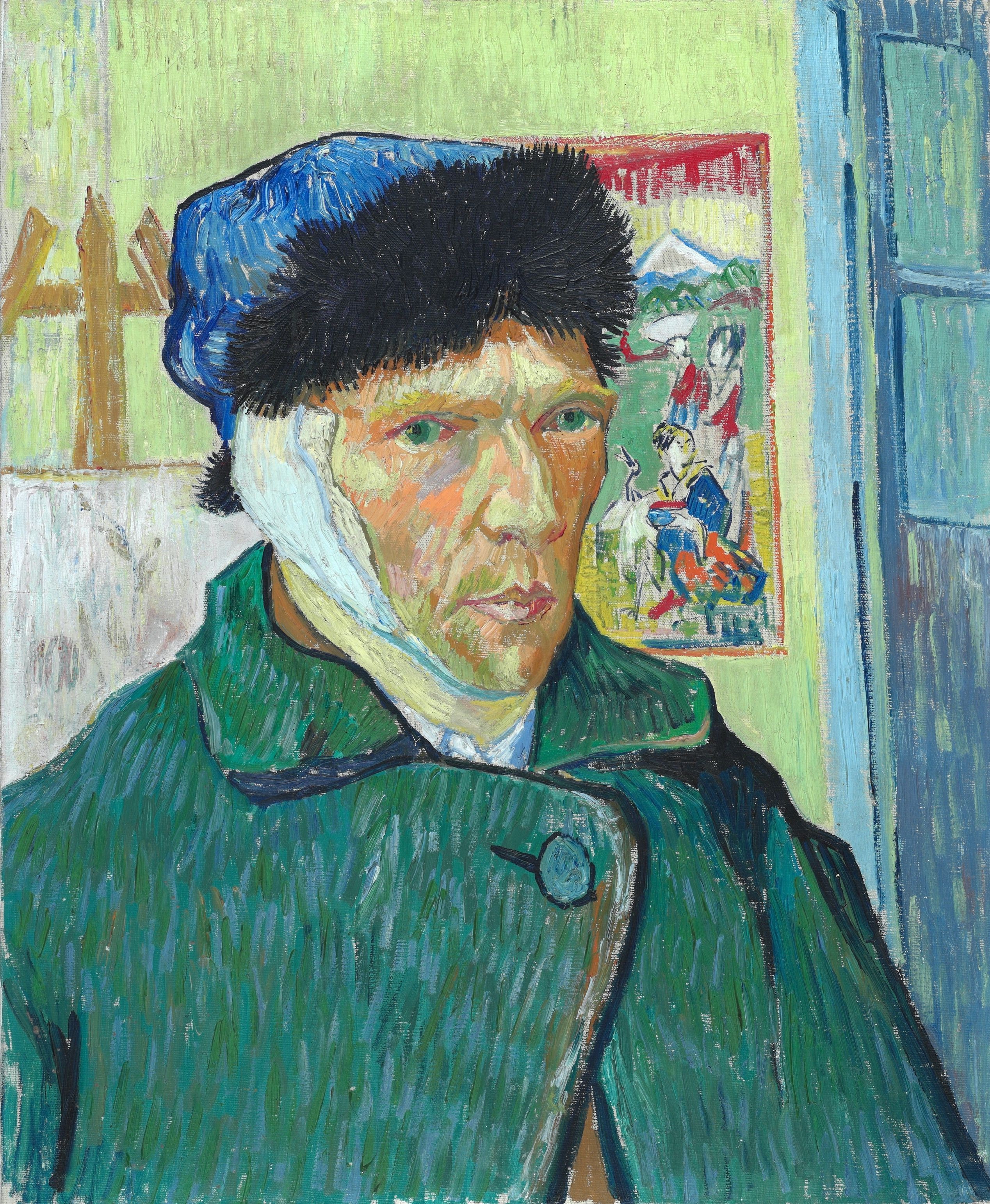

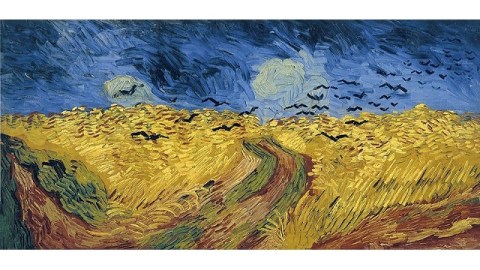

Every art lover knows the story. Sad, mad Vincent Van Gogh went into the wheat fields of Auvers-sur-Oise on the morning of July 27, 1890 to paint Wheatfield with Crows (shown above), his visual suicide note to posterity, before shooting himself in the chest. Using his amazing willpower, the wounded Vincent dragged himself almost a mile back to his room at the Auberge Ravoux, where he died two days later, his beloved brother Theo at his bedside. Can’t you just picture Kirk Douglas in Lust for Life? Can’t you almost hear Don McLean singing “Starry, Starry Night”? If Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, authors of a startling new biography of Van Gogh, are correct, everything we know about the end of Van Gogh is wrong. Could Vincent Van Gogh, the most famous martyr to art in history, actually have been murdered?

For the past ten years, Naifeh and Smith sought out every shred of information in the world about Vincent Van Gogh. (CBS’ 60 Minutes broadcast a wonderful piece on the authors and their findings that can be viewed here.) In addition to scouring Vincent’s own lyrical and revelatory letters, the authors gained exclusive access from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam to correspondence by Van Gogh’s family—letters that Vincent was never intended to see. After Van Gogh’s father died from a stroke, his mother blamed Vincent for causing the continual state of stress that brought the patriarch down. Vincent’s mad, Vincent’s mother told others, he’s always been mad. Even Theo, at least in his letters to family, maintained some distance from Vincent, or as much as he could after finding himself the sole family member willing to help Vincent in any way. The new biography goes into depth on how temporal lobe epilepsy may have plagued Van Gogh throughout his life, worsening with each new episode. Victims of temporal lobe epilepsy actually feel an attack coming on, instilling the sense of dread and doom that pervaded Vincent’s life and much of his art.

And, yet, Van Gogh found some happiness in his solitary existence. Wheatfield with Crows was not his final picture, Naifeh and Smith point out. Vincent painted several happier works between finishing that enigmatic work and the time of the shooting—a strange gap for an alleged suicide note. Naifeh and Smith also ask the rarely asked question of how Van Gogh—a well-known mental patient and all-around odd character about Auvers—could possibly have gotten his hands on a firearm? Such weapons were rare, and were rarely handed over to poor, struggling, tormented geniuses. Most importantly, how could a mortally wounded man drag himself over a mile into town? Van Gogh’s artistic drive was phenomenal, but his frail physical condition, further compromised by the bullet in his belly, forbid him from making such a trek.

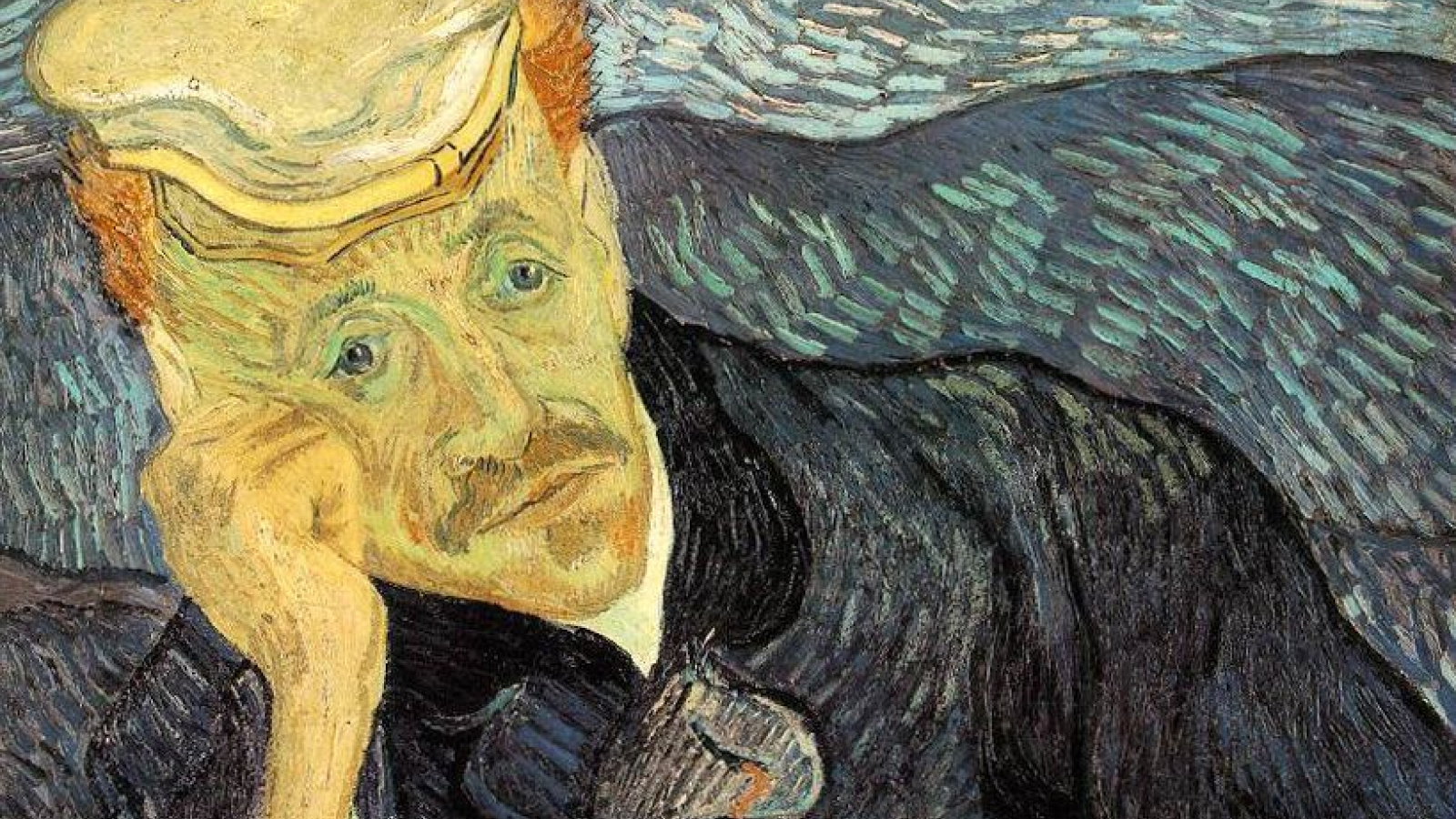

The authors of this new biography claim that Van Gogh dragged himself to his room at the inn not from the wheat field but, instead, from one of the streets of the village itself. Looking back at the notes of Dr. Paul Gachet, Van Gogh’s friend, physician, and portrait subject, Naifeh and Smith point out that Gachet noted that Van Gogh’s wound to the belly came from an odd angle almost impossible for a person to fire from on himself. The wound also came from a distance, making it unlikely that Van Gogh held the weapon when it discharged. Who did?

Naifeh and Smith uncover stories passed down in the town of Auvers of teenage boys who tormented Van Gogh by putting salt in his coffee, hiding snakes in his paint box, and encouraging their girlfriends to mock the painter with their faux advances. A semi-confession from one of those boys hidden in an obscure French medical journal suggests that Van Gogh struggled with the boys over a handgun they had borrowed when it went off accidentally (or not). That boy, speaking in advanced age in the 1950s, took the truth of the event to his grave.

When asked by police if he had tried to kill himself, Van Gogh answered, “I believe so.” Vincent followed that strange remark with the stranger words, “Don’t accuse anyone else.” If, as Naifeh and Smith argue, the murder of Vincent Van Gogh was covered up, the cover-up began with Vincent himself. Unwilling, perhaps, to end his own life, Van Gogh may have accepted the bullet as a form of “assisted suicide”—a mercy killing to end his miserable life and the misery he felt he had inflicted on Theo and the rest of his long-suffering family. Although not all Van Gogh scholars agree with this new view of the death story, if this controversial new biography’s theory is true, then the culminating event of Van Gogh’s life may have been one last picture, one last reinterpretation of reality by Vincent that we still need to interpret for ourselves.

[Image:Vincent Van Gogh. Wheatfield with Crows, 1890.]

[Many thanks to friend Dave for passing on the link to this story.]