Why Holy Men Make Lousy Popes

Nick Kristof has an idea for fixing the Catholic Church: Turn it “upside down”! Take power away from the “old boys’ club” at the Vatican, where a dark cloud hovers because of the way the old boys handle sexually abusive priests. Give the scepter instead to the other Catholic Church, “the grass-roots network of humble priests, nuns and laity in places like Sudan.” For instance, selfless Father Michael Barton, who bravely runs four schools there, “would make a great pope,” Kristof writes. Trouble is, this sort of thing has been tried already, and failed. Simple, humble people make lousy popes, because the two Catholic Churches—scheming networkers and saintly workers—are not in opposition. They’re in symbiosis, and neither can survive without the other.

In 1292, the College of Cardinals elected as Pope one Pietro da Morrone, a humble, elderly monk of great spiritual renown. His response was to refuse the office and run for the hills (actually, he was already living a life of ascetic retreat in the hills, so I guess he tried to flee for other hills). When they finally wore him down, two years later, he reluctantly became Pope Celestine V.

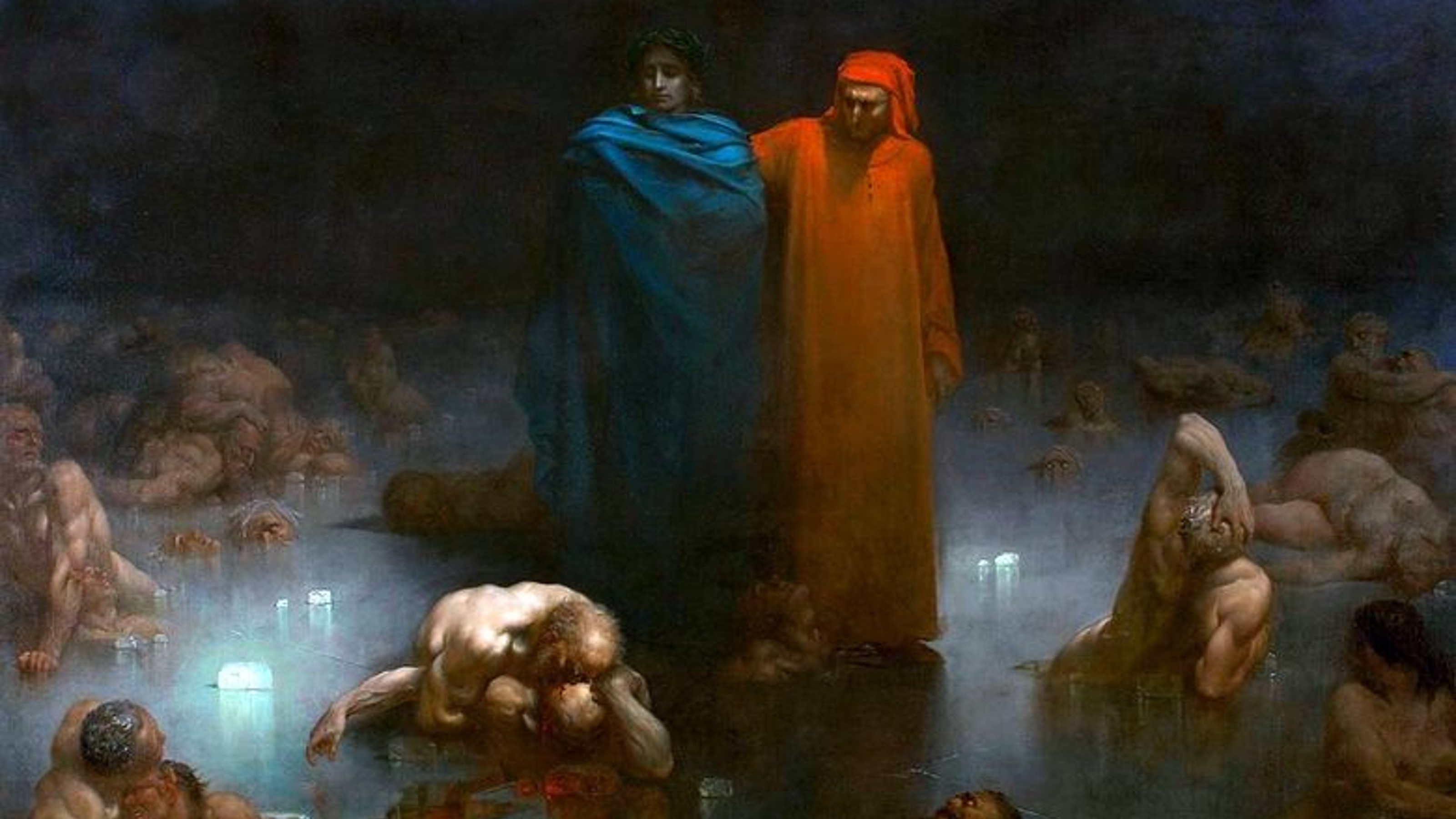

Among his notable acts was a decree permitting popes to abdicate, which he loophole he leapt for almost immediately, five months after he was crowned. Instead of returning to his tranquil cave, though, he ended up in prison, where his uneasy successor kept him until he died. For political, old-boy-network reasons, the hermit-pontiff was canonized by a later pope, but he’s gone down in history as an utter failure (there has never been another Celestine). His long life of piety forgotten, he lives on as one of literature’s most despised shirkers—the best candidate for the unnamed soul, “he who made the Great Refusal” in Dante’s Inferno. That sorry spirit is consigned to Hell’s anteroom, with the fence-sitters who wouldn’t even take a side in the fight between God and Satan.

Celestine V suffered from what the philosophers Bernard Williams and Thomas Nagel might call bad “moral luck”: He was a humble saint thrust into circumstances that demanded an able politician. Those two roles are irreconcilable.

In a Pope, commitment to personal virtue isn’t enough; the job requires commitment to preserve and protect the institution. And anyone committed to any such organization—army, political party, university, church—will have to engage in morally ambiguous acts, which seem a fair trade for the greater good of the institution’s continued existence. So the saint can refuse to lie and horse-trade and manipulate people for advantage. He can shrug off the pointless demands of bureaucratic infighting. If a Pope were to act like that, the Church would collapse.

It’s no knock on Father Michael to note that his moral luck seems to be good: He is working selflessly in a landscape where good and evil appear unambiguous. But his work depends on finances, training, authority, tradition—all of which have to be maintained by skilled bureaucrats and politicians. In other words, Kristof’s hero needs Kristof’s villains. The humble priest needs the old-boys-networks. And the old boys, of course, need humble priests. Their deeds make the institution worth defending, and so justify the politicians’ work.

I don’t believe for a moment that the abuse of children by priests can be justified on the grounds that the church as a whole does more good than harm. Nor do I think large global institutions are inevitably corrupt and unjust. But they are, inevitably, morally more difficult to run than an orphanage. The ethical demands of running an empire may be mishandled; but mishandling is not an argument for no-handling.

That’s why saintly virtue, in any religion, is surrounded by people with money and documents, and guns and truncheons. Those others patrol the perimeters of holiness. Without them, the do-gooders’ goodness would be dispersed among hindrances. So, maybe Father Michael would make a good Pope. But to avoid becoming Celestine VI, he would have to change into someone more like the former Cardinal Ratzinger.