There are 4 different types of multiverse

- The idea of a multiverse is a bit of a shapeshifter — it is taken to mean different things by different people.

- In its most basic form, the universe may be infinitely large, meaning that somewhere out there, it holds carbon copies of the very reality we inhabit. In another version of the idea, universes might have entirely different physical laws.

- Multiverses might be real, but before you can take the idea seriously, you have to define which kind of multiverse you are talking about.

The movie Everything Everywhere All at Once pretty much swept the 2023 Academy Awards. For those who have not yet seen it, the film hinges on the multiverse — the idea that there exists a series of parallel dimensions that can be similar to our own reality, yet different in some way. Without spoiling the plot of the movie, its core theme is that one small change can make a significant difference in one’s life and can even change the universe.

To take a trivial example, did you ever wonder how your life might have unfolded had you summoned the courage to talk to that unobtainable crush back in high school? Maybe it would have worked out. With the increased confidence that resulted from success, you might have gone on to be president. Small things can have a big impact.

The recent movie is a clear example of the multiverse’s impact in cinema, and it is not the only one. Movies and television have embraced the concept as a way to change existing franchises, perhaps most notably in the Marvel universe and in the more recent Star Trek movies. It’s all great fun, but it does make you wonder. Is the idea of a multiverse scientifically reputable?

That is actually a very difficult question to answer, because the definition of multiverse is a bit of a shapeshifter — it is taken to mean different things.

Infinity and inflation

While there are many different ideas of multiverses, to give a sense of the ones scientists take most seriously, it might be best to start with the different types of multiverses made popular by theoretical physicist Max Tegmark, who said that there were four.

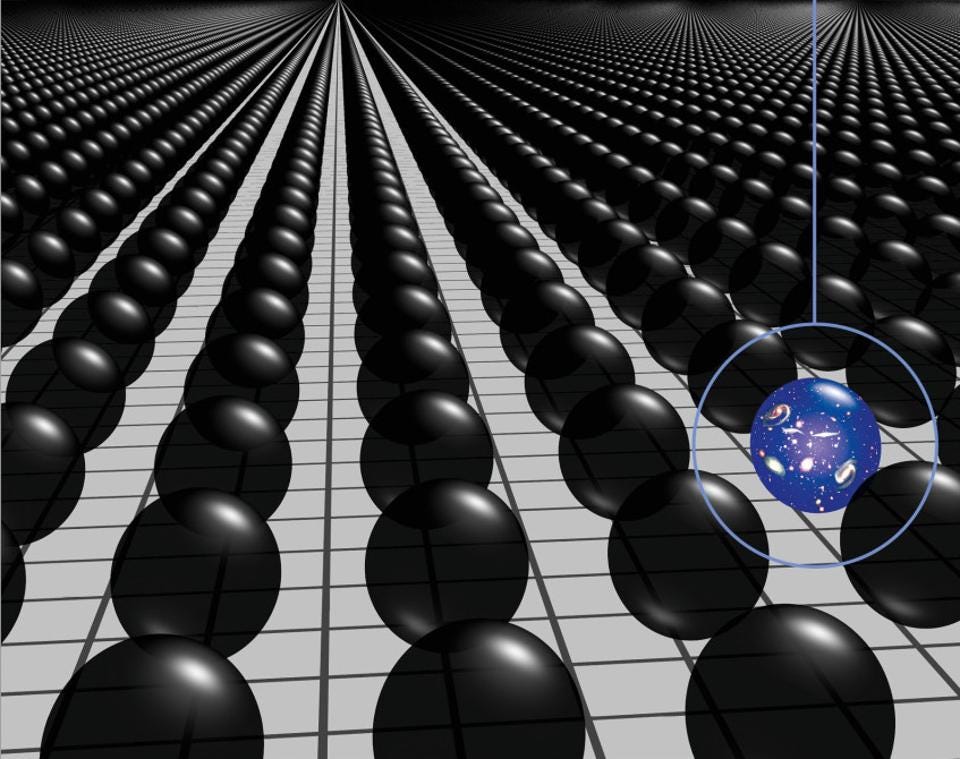

Tegmark’s first type relies on space being extremely big — indeed, perhaps infinite in size. While the visible universe is a sphere, centered on the Earth and about 92 billion light-years across, that is only the part of the universe we can see. If space is much bigger than that, then the many other pockets of space, where other stars and planets were formed, host incredible variety. And if space is infinite in size, then in one of those distant pockets there is a chunk of space that is a carbon copy of our own.

Perhaps more interesting, there is also a chunk of space that is exactly like our own, except that place’s version of you had the nerve to ask out that crush. These different realities are the first type of Tegmarkian multiverses and are the least speculative, relying only on the infinite size of space.

The second type of multiverse relies on inflation, a reputable physics theory that originated in the 1980s to explain some features of our universe — for example, why space seems to look the same no matter which direction we look, and why space does not seem to be curved back in on itself.

Basically, inflation theory says that shortly after the universe began, there was a very brief moment in which it expanded faster than the speed of light. This could explain why space seems flat, because if you take any shape, no matter how curved, and you expand it enough, it will look flat. That same physical reality allows Flat Earth advocates to claim the Earth is flat despite its being spherical — after all, the curvature is slight. Inflation also explains why the universe seems so uniform no matter where you look. If you take a small bit of space in which everything is similar, and then you expand it quickly, the bigger space also will look similar.

While inflation has not been definitively proved, the scientific community has accepted it to be plausible.

The multiplicity of multiverses

Tegmark’s third type of multiverse arises from the laws of quantum mechanics. In traditional quantum mechanics, statistical laws rule the universe. Everything is possible until we make a measurement. The most famous example is Schrödinger’s cat, a scenario that considers what happens if you put a cat in a box with a radioactive element, a glass vial of poison, and a Geiger counter that will break the vial if the element decays. Common sense says that the cat is either alive or dead, even if we do not know which. Standard quantum mechanics says that the cat is both alive and dead at the same time until you open the box and check.

However, there is a version of quantum mechanics that says when you look in the box, you actually generate two versions of reality, one in which the cat is alive and the other in which it is dead. This is called the many-worlds interpretation.

While this interpretation of the laws of quantum mechanics is not universally accepted, it is gaining some traction with scientists. In its account of multiverses, there is a constant proliferation where each decision causes another universe to come into existence. A somewhat different version tells us that all versions of reality exist. As we encounter decision points, we simply choose which reality we experience. It is certainly an interesting conjecture, and one that fascinates many introductory philosophy students.

Tegmark’s fourth type of multiverse is one in which essentially everything is different. In the first three types of multiverses, the basic laws of physics are the same, but some parameters might have different values — for example, maybe gravity is stronger in this universe and weaker in that. However, in the fourth idea, maybe the laws of physics are different in the other universes. Maybe cause and effect are different. Maybe those universes have different numbers of dimensions, like in the book Flatland by Edwin Abbott. When you allow for completely different physical laws, it is hard to imagine all the possible types of Type-4 multiverses that could exist.

When considering the idea of multiverses, it is imperative to be careful about the word. “Multiverse” means different things in different theories, and not all theories have anything to do with reality. Multiverses might be real, but before you can take the idea seriously, you have to define which kind of multiverse you are talking about.