Does science tell the truth?

Credit: Sergey Nivens via Adobe Stock / 202871840

- What is truth? This is a very tricky question, trickier than many would like to admit.

- Science does arrive at what we can call functional truth, that is, when it focuses on what something does as opposed to what something is. We know how gravity operates, but not what gravity is, a notion that has changed over time and will probably change again.

- The conclusion is that there are not absolute final truths, only functional truths that are agreed upon by consensus. The essential difference is that scientific truths are agreed upon by factual evidence, while most other truths are based on belief.

Does science tell the truth? The answer to this question is not as simple as it seems, and my 13.8 colleague Adam Frank took a look at it in his article about the complementarity of knowledge. There are many levels of complexity to what truth is or means to a person or a community. Why?

It’s complicated

First, “truth” itself is hard to define or even to identify. How do you know for sure that someone is telling you the truth? Do you always tell the truth? In groups, what may be considered true to a culture with a given set of moral values may not be true in another. Examples are easy to come by: the death penalty, abortion rights, animal rights, environmentalism, the ethics of owning weapons, etc.

At the level of human relations, truth is very convoluted. Living in an age where fake news has taken center stage only corroborates this obvious fact. However, not knowing how to differentiate between what is true and what is not leads to fear, insecurity, and ultimately, to what could be called worldview servitude — the subservient adherence to a worldview proposed by someone in power. The results, as the history of the 20th century has shown extensively, can be catastrophic.

Proclamations of final or absolute truths, even in science, shouldn’t be trusted.

The goal of science, at least on paper, is to arrive at the truth without recourse to any belief or moral system. Science aims to go beyond the human mess so as to be value-free. The premise here is that Nature doesn’t have a moral dimension, and that the goal of science is to describe Nature the best possible way, to arrive at something we could call the “absolute truth.” The approach is a typical heir to the Enlightenment notion that it is possible to take human complications out of the equation and have an absolute objective view of the world. However, this is a tall order.

It is tempting to believe that science is the best pathway to truth because, to a spectacular extent, science does triumph at many levels. You trust driving your car because the laws of mechanics and thermodynamics work. NASA scientists and engineers just managed to have the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter — the first man-made device to fly over another planet — hover above the Martian surface all by itself.

We can use the laws of physics to describe the results of countless experiments to amazing levels of accuracy, from the magnetic properties of materials to the position of your car in traffic using GPS locators. In this restricted sense, science does tell the truth. It may not be the absolute truth about Nature, but it’s certainly a kind of pragmatic, functional truth at which the scientific community arrives by consensus based on the shared testing of hypotheses and results.

What is truth?

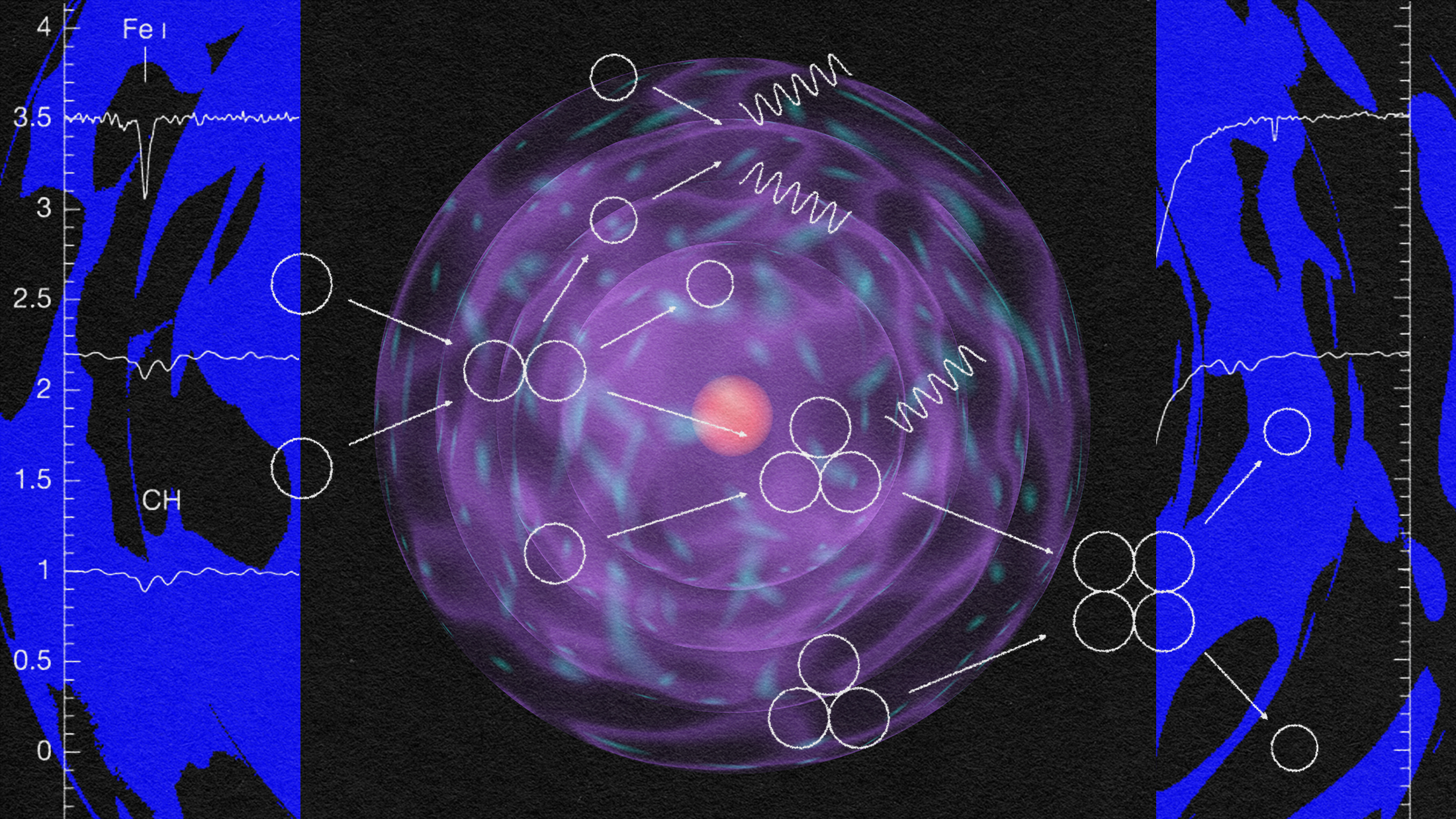

But at a deeper level of scrutiny, the meaning of truth becomes intangible, and we must agree with the pre-Socratic philosopher Democritus who declared, around 400 years BCE, that “truth is in the depths.” (Incidentally, Democritus predicted the existence of the atom, something that certainly exists in the depths.)

A look at a dictionary reinforces this view. “Truth: the quality of being true.” Now, that’s a very circular definition. How do we know what is true? A second definition: “Truth: a fact or belief that is accepted as true.” Acceptance is key here. A belief may be accepted to be true, as is the case with religious faith. There is no need for evidence to justify a belief. But note that a fact as well can be accepted as true, even if belief and facts are very different things. This illustrates how the scientific community arrives at a consensus of what is true by acceptance. Sufficient factual evidence supports that a statement is true. (Note that what defines sufficient factual evidence is also accepted by consensus.) At least until we learn more.

Take the example of gravity. We know that an object in free fall will hit the ground, and we can calculate when it does using Galileo’s law of free fall (in the absence of friction). This is an example of “functional truth.” If you drop one million rocks from the same height, the same law will apply every time, corroborating the factual acceptance of a functional truth, that all objects fall to the ground at the same rate irrespective of their mass (in the absence of friction).

But what if we ask, “What is gravity?” That’s an ontological question about what gravity is and not what it does. And here things get trickier. To Galileo, it was an acceleration downward; to Newton a force between two or more massive bodies inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them; to Einstein the curvature of spacetime due to the presence of mass and/or energy. Does Einstein have the final word? Probably not.

Is there an ultimate scientific truth?

Final or absolute scientific truths assume that what we know of Nature can be final, that human knowledge can make absolute proclamations. But we know that this can’t really work, for the very nature of scientific knowledge is that it is incomplete and contingent on the accuracy and depth with which we measure Nature with our instruments. The more accuracy and depth our measurements gain, the more they are able to expose the cracks in our current theories, as I illustrated last week with the muon magnetic moment experiments.

So, we must agree with Democritus, that truth is indeed in the depths and that proclamations of final or absolute truths, even in science, shouldn’t be trusted. Fortunately, for all practical purposes — flying airplanes or spaceships, measuring the properties of a particle, the rates of chemical reactions, the efficacy of vaccines, or the blood flow in your brain — functional truths do well enough.