More than 1,500 rocket scientists gathered at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena last Friday for a funeral they’d known was coming for years. There were tears, but mostly, it was a celebratory occasion.

They had gathered to say goodbye to . . . a satellite.

And so they toasted Cassini, a space probe that had launched October 15, 1997 and traveled almost 5 billion miles. It spent the last 13 years orbiting Saturn, sending back all kinds of data and astonishing photos of the planet, its magnificent rings, and its many moons. As they raised their glasses on Friday morning, Cassini was falling out of orbit and plunging to its planned demise, burning up like a meteor in Saturn’s atmosphere, going out in a blaze of glory.

“It was a perfect spacecraft,” said Julie Webster, spacecraft operations chief. “Right to the end, it did everything we asked it to.”

Watch NASA’s spectacular video, Cassini: The Wonder of Saturn, here:

Or better yet, check out NASA’s amazing interactive app, Eyes on Cassini.

The beginning of the end came when mission controllers steered Cassini, running out of fuel, on a risky path through the gaps between Saturn and its inner rings, and ultimately to its fiery ending. They decided to destory it rather than run the risk of letting it wander, uncontrolled, in orbit among Saturn’s rings and moons.

“This is the final chapter of an amazing mission, but it’s also a new beginning,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “Cassini‘s discovery of ocean worlds at Titan and Enceladus changed everything, shaking our views to the core about surprising places to search for potential life beyond Earth.”

Titan and Enceladus are among Saturn’s 62 moons (53 of which have been named). Cassini and its partner, Huygens, which landed on Titan in 2005, revealed that the two moons (Titan, Enceladus) have remote potential for very primitive forms of life. But it’s a long, long shot.

Most people will remember Cassini for the many spectactular images it sent back to earth. In the shot at the top of this page, Cassini looks back at Saturn, which is blocking out the sun. This panoramic view was created by combining a total of 165 images taken by the Cassini wide-angle camera over nearly three hours on Sept. 15, 2006.

And then there are these:

A portion of the inner-central part of the planet’s B Ring (2017):

Saturn’s northern hemisphere (2016):

The unique six-sided jet stream at Saturn’s north pole known as “the hexagon” (2012):

Jets spurting ice particles and water vapor from the moon Enceladus (2007):

Saturn’s largest and second largest moons, Titan and Rhea (2013):

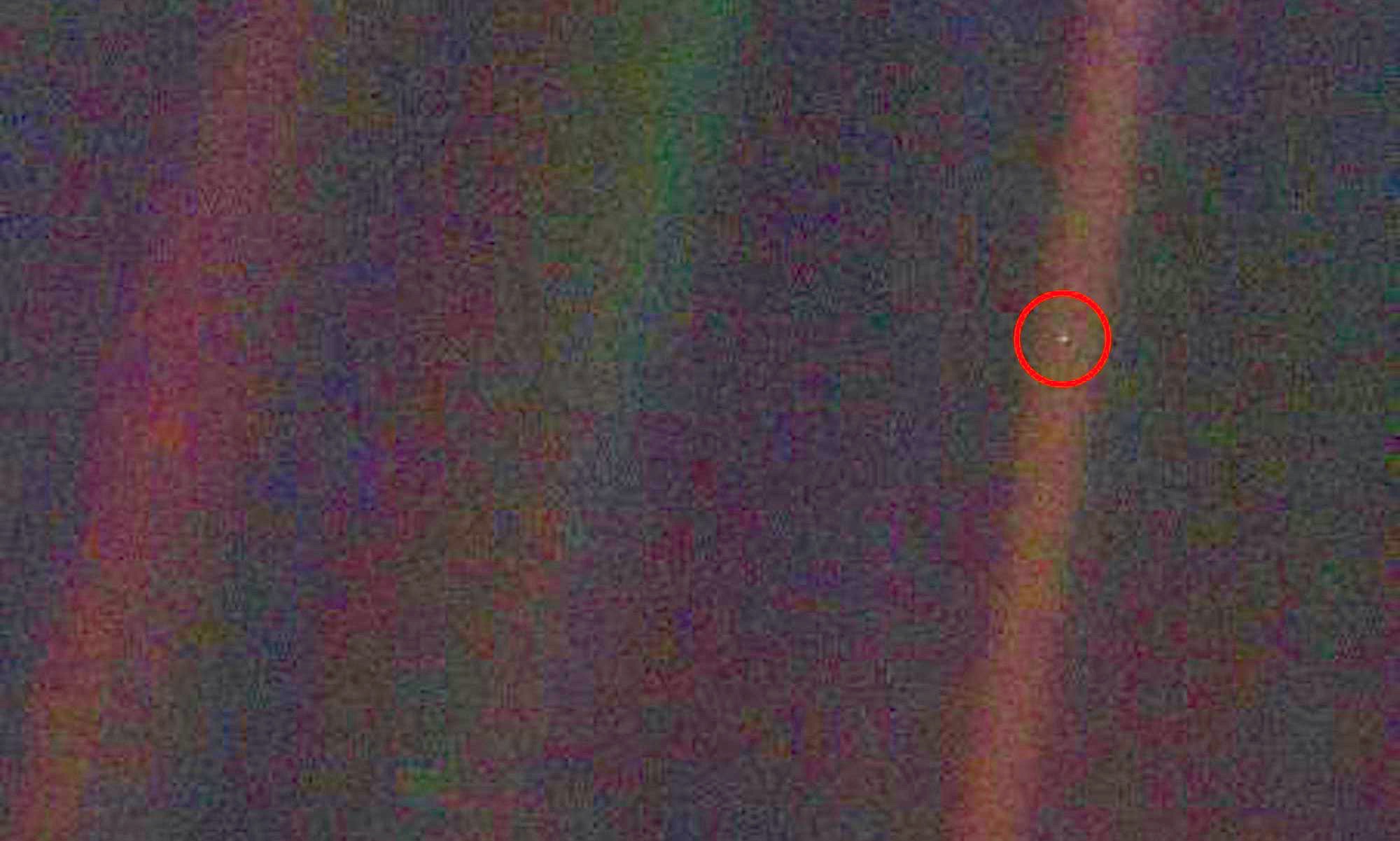

Looking back past the rings at planet Earth (arrow) (2013):

For a great roundup of the mission, including more astonishing images, download a free copy of NASA’s eBook, The Saturn System Through the Eyes of Cassini.

“The spacecraft did everything we asked it to do—everything—right to the very end,” said NASA’s Webster. “That’s all you want for any human, let alone a robot.”

“There are times in this world when things just line up, when everything is just about perfect,” said program manager Earl Maize. “A child’s laugh, a desert sunset and this morning. It just couldn’t have been better. Farewell, faithful explorer.”

Project scientist Linda Spilker, who had a handkerchief to wipe away tears, said Cassini‘s demise “felt so much like losing a friend.”

Even science writers got a little mushy in their farewells.

“Saying goodbye feels both profoundly sad and a little strange—it’s like parting with a longtime friend that you’ve never actually met,” writes Rae Paoletta in Gizmodo. “In this scenario, that friend is a hunk of metal hurtling through the void, but it feels human nonetheless . . . . Thank you for reminding us what makes this Pale Blue Dot—and the people on it—so unreasonably and spectacularly special. Ad astra, Cassini.”

The post So Long, Cassini appeared first on ORBITER.