Cheap liver drug could prevent COVID

- Many of the cells in our body have a protein called ACE2 on their surfaces, and the coronavirus uses this protein like a doorway to gain entry into our cells.

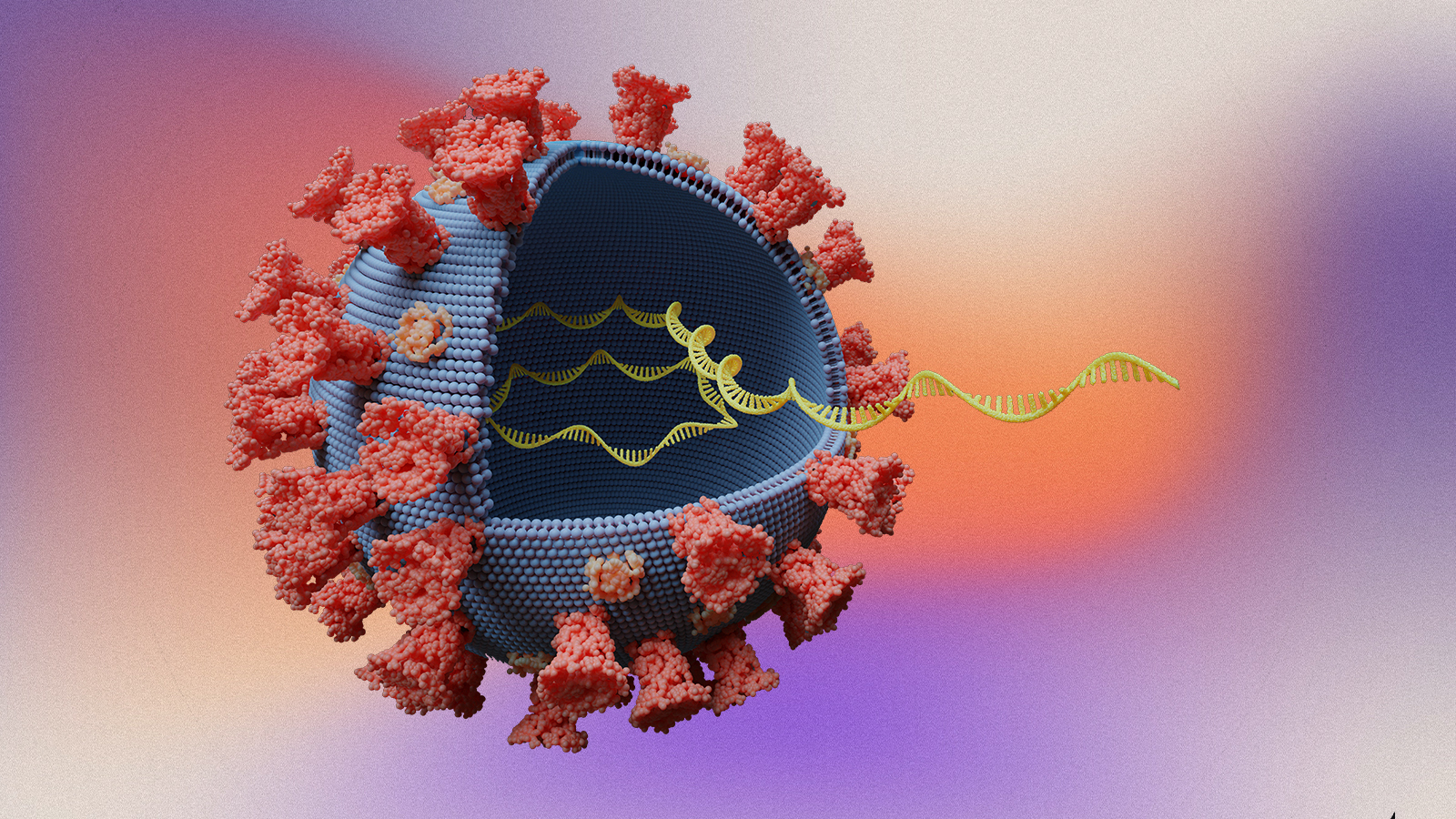

- Using bile duct organoids, researchers discovered that a molecule called FXR regulates ACE2.

- FXR has been linked to common liver diseases, and by treating their organoids with a drug prescribed for those diseases, called UDCA, the researchers found they could decrease the expression of ACE2 on the cells and essentially close the doorway.

Scientists at the University of Cambridge have discovered that a cheap, readily available drug used to treat liver disease can also prevent COVID-19 infections.

“We are optimistic that this drug could become an important weapon in our fight against COVID-19,” said lead researcher Fotios Sampaziotis.

The discovery: Many of the cells in our body have a protein called “ACE2” on their surfaces, and the coronavirus uses this protein like a doorway to gain entry into our cells.

“We showed that an existing drug shuts the door on the virus and can protect us from COVID-19.”

TERESA BREVINI

The Cambridge researchers were studying bile duct organoids — tiny, three-dimensional clumps of cells that can take on the function of a larger organ — when they discovered that a molecule prevalent in their mini bile ducts, called FXR, regulates ACE2.

FXR has been linked to common liver diseases, and by treating their organoids with a drug prescribed for those diseases — ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) — the researchers discovered they could decrease the expression of ACE2 on the cells and essentially close the doorway.

The tests: The next step in the research was testing the approach in organoids designed to mimic the lungs and the gut — the coronavirus’ two main targets. The mini lungs and guts were treated with the drug and then exposed to the virus — but it couldn’t infect their cells.

After that, the Cambridge group teamed up with researchers at the University of Liverpool for hamster testing, and as hoped, the liver drug was able to prevent COVID-19 infections in treated animals exposed to the virus.

Tests on donated human lungs — unsuitable for transplantation and kept “alive” on a ventilator — were next. Just one lung in a pair was treated with UDCA before both were exposed to the coronavirus. The treated lung did not become infected, but the untreated one did.

To find out whether UDCA might prevent COVID-19 in people, the Cambridge team and researchers at the University Medical Centre Hamburg-Eppendorf treated eight healthy volunteers with the liver drug.

“When we swabbed the noses of these volunteers, we found lower levels of ACE2, suggesting that the virus would have fewer opportunities to break into and infect their nasal cells — the main gateway for the virus,” said Ansgar Lohse, a researcher at the hospital.

UDCA isn’t 100% effective at stopping infection, but when the Cambridge team looked at existing data to compare the outcomes of COVID-19 patients who were taking the drug to those who weren’t, they discovered that those on UDCA were less likely to develop severe infections or be hospitalized.

“Using almost every approach at our fingertips we showed that an existing drug shuts the door on the virus and can protect us from COVID-19,” said first author Teresa Brevini.

Why it matters: The approval of highly effective COVID-19 vaccines was a game changer in the pandemic, but because the shots prevent COVID-19 by training the immune system to target the virus, they aren’t a viable form of protection for people with weak immune systems.

The vaccines have also proven less effective against new COVID-19 variants, and as we learned from the bivalent boosters targeting Omicron, by the time updated versions of the shots are approved, even newer variants are already circulating.

“It might be the only line of protection while waiting for new vaccines to be developed.”

FOTIOS SAMPAZIOTIS

UDCA is well-tolerated by users and can be taken indefinitely as a treatment for liver disease — that makes it a promising alternative to COVID-19 vaccines for people with weak immune systems. Because it targets the ACE2 protein on our cells — and not the coronavirus itself — it should be just as effective against future variants as the ones currently circulating, too.

It’s not clear whether the Cambridge team plans to conduct trials to determine just how effective UDCA is at preventing COVID-19, but the researchers are bullish on its potential.

“This tablet costs little, can be produced in large quantities fast and easily stored or shipped, which makes it easy to rapidly deploy during outbreaks — especially against vaccine-resistant variants, when it might be the only line of protection while waiting for new vaccines to be developed,” said Sampaziotis.

This article was originally published on our sister site, Freethink.