Leonardo da Vinci could visually flip between dimensions, neuroscientist claims

Christopher Tyler

- A neuroscientist at the City University of London proposes that Leonardo da Vinci may have had exotropia, allowing him to see the world with impaired depth perception.

- If true, it means that Da Vinci would have been able to see the images he wanted to paint as they would have appeared on a flat surface.

- The finding reminds us that sometimes looking at the world in a different way can have fantastic results.

An analysis of Renaissance artwork suggests that Leonardo Da Vinci may have had exotropia, a kind of strabismus which causes one of the eyes to be turned outwards, and that the condition may have helped him as a painter by allowing him to switch between three-dimensional and two-dimensional vision. He wouldn’t have been alone, other famous painters who are speculated to have had the condition include Rembrandt and Picasso.

The Virtuvian Man. Christopher Tyler suggests that Da Vinci used his own image as a template for the face in the drawing.

Vitruvian Man, by Leonardo da Vinci created c. 1480–1490

The study

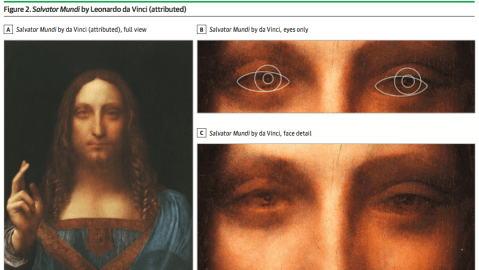

Professor Christopher Tyler of the City University of London’s optometry division analyzed six pieces of Renaissance art by or held to be images of Da Vinci, including the famous Vitruvian Man. By looking at the paintings, drawings, and statues and applying the same techniques optometrists use on patients, Tyler was able to conclude that the eyes of the men depicted were misaligned.

He concluded that, if the images he analyzed were truly reflective of how Da Vinci looked, that the great artist had a mild case of exotropia.

How would this have helped him paint?

Shira Robbins, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of California at San Diego, who was not involved with the project, explained to The Washington Posthow individuals with exotropia often turn to additional information to help understand the world around them:

“What happens in some people is when they’re only using one eye . . . they develop other cues besides traditional depth perception to understand where things are in space, looking at color and shadow in a way that most of us who use both eyes at a time don’t really appreciate.”

Dr. Robbins agrees that, if the artworks analyzed accurately depict Da Vinci, then he probably had exotropia.

If Da Vinci did have a mild form of the condition, which would allow him to focus with both eyes when concentrating and with one when relaxed, Tyler asserts that the famed artist could have viewed the world in two or three dimensions at will, showing him the world exactly as he would need to recreate it on a flat surface. Quite the superpower for an artist.

Christopher Tyler

A graph showing the difference in where each eye is focused for each painting, drawing, and statue used in the study. The larger the difference, the more pronounced the exotropia is in the image.

Does this mean Da Vinci would have been a hack if he had normal eyesight?

Not at all. What Dr. Tyler is suggesting is that the tendency of people who have exotropia to rely on using one eye to see the world and thereby lose some depth perception allowed Da Vinci to understand better how the three-dimensional objects in the world could be translated into a two-dimensional image on a canvas. This could account for some of Da Vinci’s skill in depicting shadow and subtle changes in color, since he would have relied on these details to understand the world.

His polymathic brilliance extended far beyond art, and nobody is claiming that his ideas for flying machines, tanks, or other inventions were at all influenced by a vision problem.

How can we know this? He has been dead for five hundred years.

There are reasons to be cautious anytime we make claims about people who are long dead. In this case, we have the bonus problem that we aren’t 100 percent sure that the images used are supposed to look like Da Vinci.

That is the major caveat of the idea; all of the images used as evidence of his condition are assumed to look like him. While some of the images, like the David by Andrea del Verrocchio, are generally agreed to be based on Leonardo the other pictures are claimed to be reflective of him based only on his statement that “[The soul] guides the painter’s arm and makes him reproduce himself, since it appears to the soul that this is the best way to represent a human being.”

Tyler also argues that the portraits he claims are based on Da Vinci share similarities with the images generally accepted to be portraits of him; including similar hair and facial features. This lends weight to the idea that the artist incorporated his own traits into his artwork, including his vision problem.

Leonardo da Vinci was undoubtedly one of the greatest geniuses of all time. If he had exotropia, then it was merely a minor addition to his artistic skills. It does, however, give us a literal example of how people who look at the world differently can use that vantage point to their advantage to create things we all can appreciate.