Scientists are producing deadly zoonoses on this tiny German island

Google Maps

- The Friedrich Loeffler Institute in Germany is a biosafety level 4 facility where scientists conduct dangerous research on zoonoses.

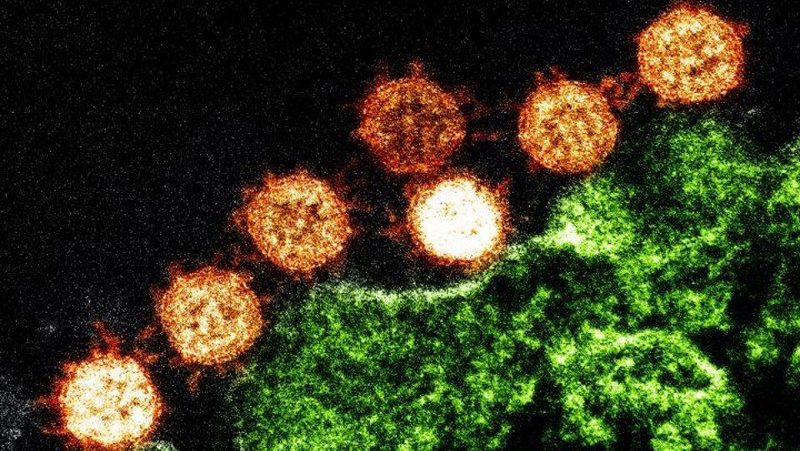

- Zoonoses are diseases that can be spread from animals to humans, or vice versa.

- These diseases not only pose a major threat to humans, but also to animals.

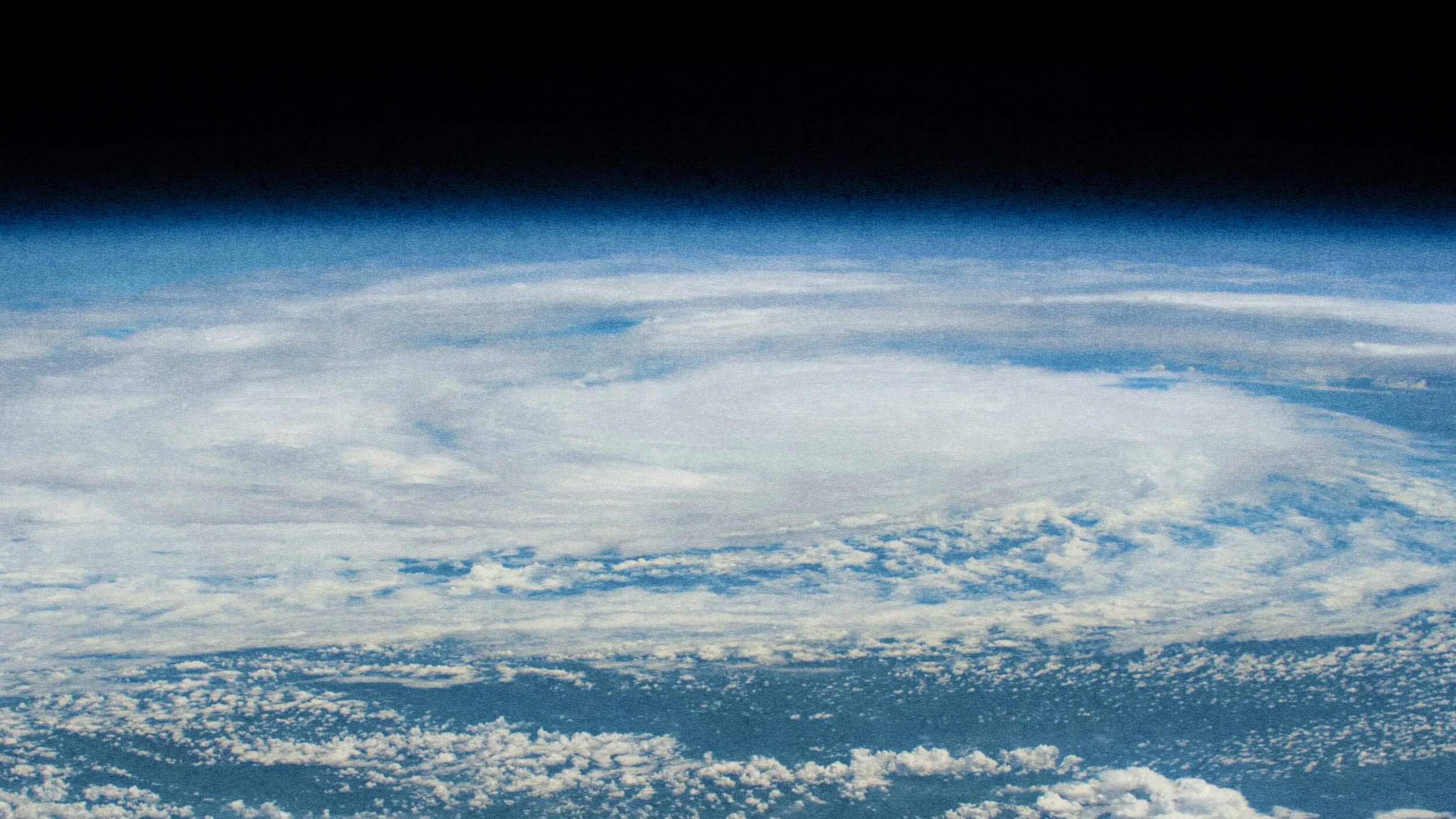

On a small, unassuming German island called Riems lies one of the oldest virus research institutes in the world. And also one of the most dangerous.

The Friedrich Loeffler Institute is closed to the public. To access the island, approved visitors must first cross a small stretch of the Baltic Sea via a dam, which can be closed immediately in case of an outbreak. To enter the facility, they must take a shower and put on protective clothing. Inside, scientists study some of the world’s most deadly viruses, including bird flu, Ebola and mad cow disease.

One of their many focuses is zoonoses, which are diseases that can be spread from animals to humans, or vice versa. But the facility was originally founded in 1910 to study foot-and-mouth disease. Over the following decades, the Friedrich Loeffler Institute was used for various purposes, including the development of chemical weapons during World War II, vaccine research during the Cold War, and the study of animal welfare and husbandry. It eventually earned the nickname the “island of plagues.”

In 2010, the Friedrich Loeffler Institute completed construction on a series of new laboratories that are classified as biosafety level 4, one of the most dangerous distinctions. Today, there are only a handful of level-4 facilities worldwide.

Map of level-4 facilities

The institute is also one of only two facilities worldwide with the ability to conduct large-scale animal studies, such as with swine and cattle. Robin Holland, a student in the Veterinary Medical Scholars Program at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine, described her experience studying pathology at the Friedrich Loeffler Institute like this:

“I learned how these diseases are managed, controlled, and diagnosed in real-world scenarios, their prevalence globally, and their potential for economic impact if outbreaks were to occur in a naïve population.”

University of Greifswald

Holland also described the containment procedures at the institute.

“Alongside engineers and biorisk officers, I saw the massive infrastructure of the FLI, including HEPA filtration of exhaust air, room decontamination by dry fogging, waste water treatment, and carcass rendering to animal byproducts. I learned how the level 2 through 4 facilities are managed, protocols for containment in the event of an emergency, and how facilities are designed and personnel are trained in order to ensure that—especially considering work with highly contagious pathogens such as FMDV—all pathogens are contained within the facility.”

Zoonoses: A bigger threat to humans or animals?

Zoonoses pose a major threat to humans. From malaria to rabies, they account for about 60 percent of all infectious diseases contracted by humans, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that “3 out of every 4 new or emerging infectious diseases in people are spread from animals.” But as scientists continue to study how to treat, prevent and contain these infectious diseases, it’s also worth noting the threats they pose to animals.

“The animal toll has been much greater,” neurobiologist and public health physician Professor Charles Watson from Curtin University told Abc.net. “When the Nipah virus broke out in Malaysia in the late 1990s there were relatively few human deaths but five million pigs had to be slaughtered in order to wipe it out.”

One reason zoonoses are so deadly for animals is that some mysteriously don’t hurt humans, even when we contract them.

“It is really unpredictable, however many viruses are successful because they do not kill their human hosts and therefore get better transmission from person to person.”