Maia Szalavitz: Drug testing is like a big business and one of the key people in the big business of drug testing is a guy who once testified in favor of one of the most abusive rehabs in American history. And he now is like a big wig in the drug testing field. And this program literally tortured people. They would like hold the kids down on the floor, until they wet or soiled themselves, as a punishment. They would punch them. They would sleep deprive them for like 48 or 72 hours. They would make them go through a spanking machine. I mean it was all kinds of really stupid, horrible, traumatic—and they would constantly emotionally attack these kids in order to break them. 50,000 American kids went through this program, which was known as Straight Incorporated. And the people who enabled it, the people who said this was the best program are still out there trying to sell monitoring for people who use drugs. And I find that offensive. I just think that if you have done something that is so harmful to people, that left many families broken and left at least thousands of people with PTSD, that you probably should not be having anything to do with anybody who uses drugs.

Addiction is a very human problem and this is often why people propose and some people benefit from a spiritual solution to it. That's not to say we should treat medicine and medical conditions as spirituality, but the reality is that addiction and depression and a lot of other mental illnesses do often involve struggling with that potential question.

And so it is not going to be the case that you can just put a brain implant in and addiction it will go away without a big chunk of yourself going away. So the Chinese are horribly experimenting with this horrific brain surgery where they ablate, i.e. burn out, the nucleus accumbens, which is basically the brain region that provides pleasure and motivation, and they think that this is actually going to cure addiction. Of course, what happens is you get people who are just anhedonic, who relapsed because now they have even less.

So this idea that like we could use a drug that would block the effects of the drug of choice is generally misguided because the problem isn't the drug of choice. The problem is: why do you need that drug, and why do those drugs appeal to you, and why you are trying to get out? Why you are trying to escape? And what you need in your life in order to feel comfortable and safe and productive? So I don't think that there will be future weird cures like that. But what I do think is interesting about the future of drugs is that we can make better drugs.

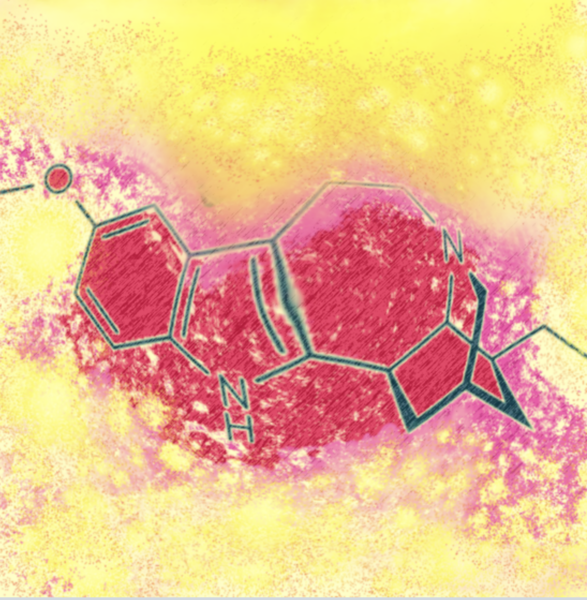

Part of the reason that prohibition is collapsing at the moment is because of what are called new psychoactive substances or legal highs. And basically you can make a new recreational drug by sort of tweaking molecules of the other ones, and it will be technically legal because it hasn't been made illegal. And what this reveals is that our system for making drugs illegal is completely irrational and based on 19th century prejudices. It has nothing to do with science. And if we apply science to this problem and look at—well, people are always going to want to alter their consciousness in some ways, how do we reduce the harm associated with this? How do we create drugs or medications that will allow people to feel safe and comfortable in the world but not be so distracting or problematic that they will not be able to connect with other people, they won't be so out of it?

So I think the future of drugs is better drugs. I don't think the future of drugs will be—or, you know, virtual reality; these kinds of things could all be very interesting, but I think that so long as people ask the question, "Why am I here?" and so long as people need each other to love and connect, we are going to have people who want to find ways to make that work better.