Therapy dogs help patients in the emergency room

- Scientists at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada conducted a study to see if a ten-minute session with a therapy dog would benefit patients visiting a hospital emergency room.

- Patients who received a therapy dog session reported improvements in pain, anxiety, depression, and well-being while control subjects did not.

- Having a therapy dog in an emergency department could be beneficial, at least for patients who like dogs and aren't allergic.

Visiting a hospital’s emergency room is no fun. Patients are pained and stressed by their sudden maladies or unfortunate injuries. Being forced to wait for treatment during busy hours makes the situation even worse. But according to a new study published in the journal PLoS ONE, a therapy dog can help.

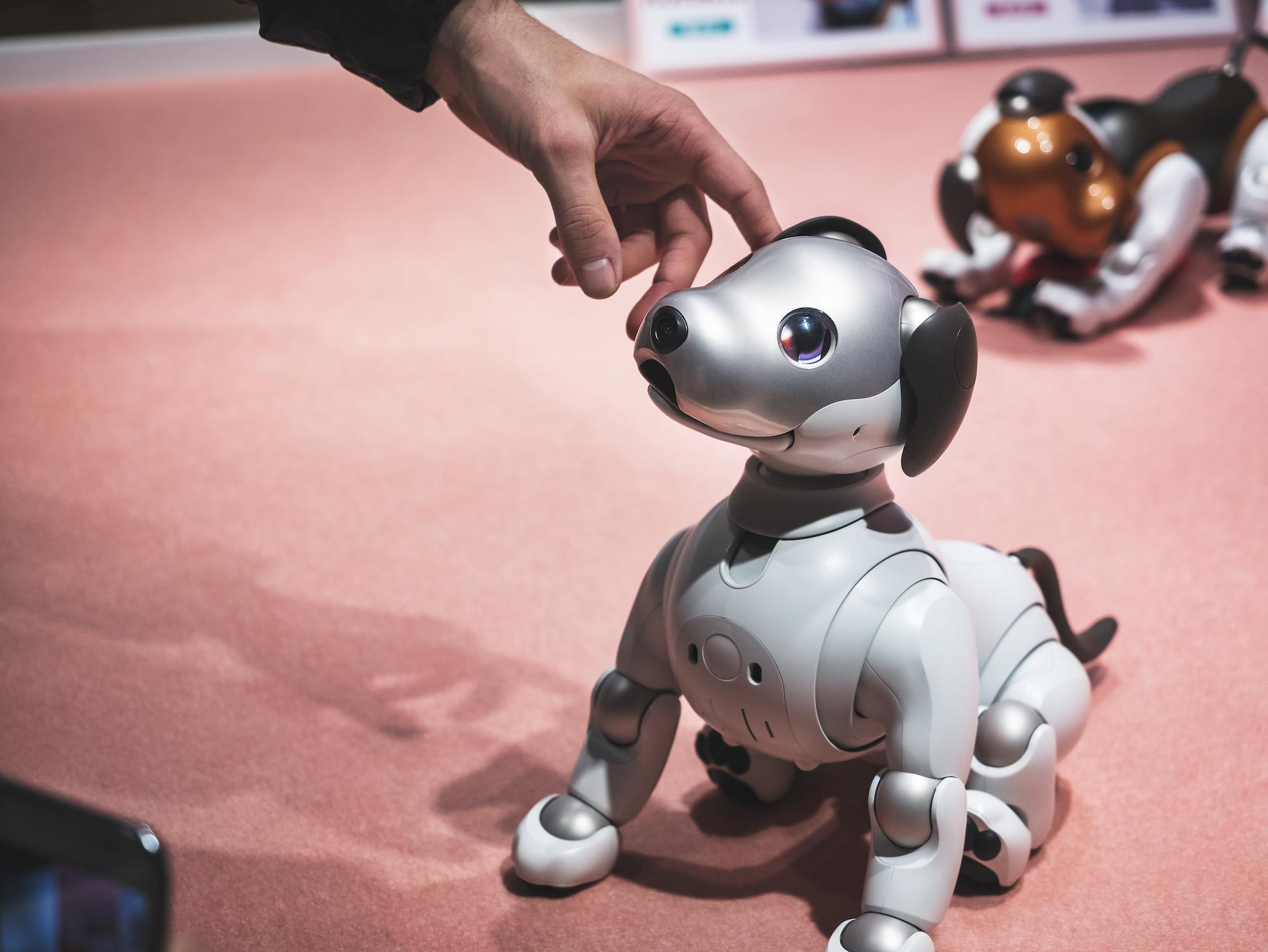

Those fluffy, four-legged friends known as therapy dogs frequently make appearances at airports, schools, nursing homes, and yes, hospitals. Chosen for a calm demeanor, gentle disposition, and friendliness to strangers, therapy dogs are further trained to be relaxed in frenetic situations and to ignore distractions that would tempt most dogs. Their comforting effects may seem self-evident, at least to animal lovers, but scientists surprisingly have yet to quantify them in an emergency department setting.

Paw patrol

So, researchers primarily associated with the University of Saskatchewan in Canada set up an experiment in which some patients visiting the Royal University Hospital Emergency Department received a ten-minute visit from a certified therapy dog and its handler while other patients did not. They then compared the two groups’ self-reported pain, anxiety, well-being, and depression.

Here’s how the experiment went: On various days during the summer of 2019, a research assistant visited patients at the emergency department who were either waiting to be seen by a physician, had treatment in progress, or were admitted and waiting for a bed, asking if the patients would like to participate in a “pain study.” For those who said yes, the research assistants took baseline measurements for pain, anxiety, well-being, and depression using an 11-point scale. The assistants also measured patients’ heart rate and blood pressure.

Soon after, some patients received a ten-minute session with a therapy dog after giving their consent to a visit, immediately after which their health measurements were taken again. They were assessed yet again 20 minutes later. Control patients did not receive a therapy dog session and simply had their health measurements taken 30 minutes after their initial assessment. In total, 101 patients ended up in the control group, while 97 were in the therapy dog “treatment” group.

The researchers found that patients who visited with the therapy dog reported about a one-point improvement in pain, anxiety, well-being, and depression, “a positive, though small, impact,” they said. Patients who didn’t receive the intervention reported no changes whatsoever. Heart rate and blood pressure were not impacted in either group.

“Interactions with a therapy dog may alleviate pain perception by serving as a distraction from symptoms,” the researchers speculated. This can have real clinical effects, they noted, citing a prior study in which patients recovering from a total joint replacement surgery who were visited by therapy dogs ended up using less pain medication than patients who were not visited.

A better control would have been nice

A key limitation of the study was the control group. In the experiment, control subjects received no intervention at all, but it might have been better for them to have been visited by a handler without the dog and to simply have a polite discussion. “This would establish whether or not the animal is necessary to the success of the interaction,” the researchers wrote.

While the benefits of a therapy dog visit as shown by this study are by no means groundbreaking, they might just improve patient outcomes, ease hospital workers’ jobs, and make time spent at a hospital emergency room a little more enjoyable, at least for people who like dogs and aren’t allergic.