Oral bacteria trigger rheumatoid arthritis flare-ups

- Periodontal (gum) disease is more common in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, implicating the former in causing the latter.

- Results from a longitudinal study of rheumatoid arthritis patients suggest that periodontal disease results in repeated breaches of the oral mucosa that release oral bacteria into the blood, triggering inflammation.

- Furthermore, these invading microbes share patterns with human joint proteins, resulting in antibodies that attack both the bacteria and the joint.

Periodontal (gum) disease affects up to 47% of the U.S. adult population and is thought to be linked to a wide variety of adverse health outcomes, from dementia to pancreatic cancer. It was suspected that oral health also plays a role in the development of rheumatoid arthritis, and now, a team led by scientists at Stanford University have discovered a possible mechanism: Oral bacteria infiltrate the bloodstream and trigger the production of antibodies that target both the microbial invaders as well as healthy proteins found in human joints. Their results were reported in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Invasion of the oral bacteria

Periodontal disease (PD) deteriorates the gums, which are responsible for holding your teeth in place and keeping oral bacteria from entering the bloodstream, where they can cause systemic inflammation. Furthermore, PD is more common in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. These and other clues led Stanford researchers to speculate that the disease could somehow trigger immune pathways that drive chronic inflammation in joints.

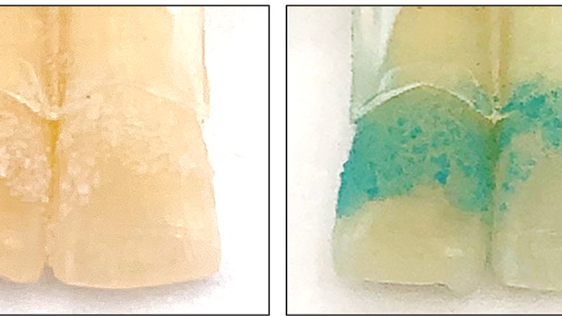

To test this, they first needed to determine if rheumatoid arthritis patients with PD were more vulnerable to invasion by oral bacteria than rheumatoid arthritis patients with healthy gums. The researchers collected and compared blood samples from five rheumatoid arthritis patients with PD and five without PD. They found that those with gum disease had a high abundance of oral bacteria in their blood.

Previous studies have shown that rheumatoid arthritis patients with persistent gum disease experience more frequent arthritis flare-ups — periods when symptoms worsen and medications don’t seem to work — compared to rheumatoid arthritis patients without gum disease. Therefore, the authors of the recent study wanted to determine whether the increased bacterial burden in arthritis patients with PD contributed to an arthritis flare-up.

To do so, they compared gene expression during flare-ups in arthritis patients with and without PD and found that patients with PD had higher levels of expression for genes associated with an immune response, such as inflammation and antibody production. This was truly a remarkable finding. For decades, scientists have known that rheumatoid arthritis manifests as an overactive inflammatory response caused by malfunctioning antibodies. However, they didn’t know what prompts the body to produce those antibodies. Based on the gene expression results, the Stanford scientists explored the possibility that wayward oral bacteria were responsible for activating these arthritis-causing antibodies.

Friendly fire

When an antibody binds to something (called an antigen), it informs the rest of the immune system that it has found something that needs to be destroyed. This is good when they bind to harmful things, like pathogens and tumors, but bad when they bind to harmless things, like tree pollen (which causes allergies) or healthy body proteins (which causes autoimmune disease). Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disorder that develops when antibodies bind to important joint proteins.

One of the most common targets of arthritis-causing antibodies is citrullinated proteins — that is, proteins whose arginine (an amino acid) residues have been converted to citrulline (another amino acid). Around 60% to 70% of rheumatoid arthritis patients express anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs). Because the researchers had observed that flare-ups in arthritis patients with gum disease were associated with increased antibody activity, they reasoned that the patients must have antibodies that recognize both the joint tissue and the oral bacteria. Indeed, when they analyzed oral bacteria, they found that many possessed citrullinated proteins.

Antibodies tend to be highly specific, binding to very few different targets. The mere presence of citrullinated proteins in oral bacteria does not prove that ACPAs bind to them. To determine this, the researchers harvested antibodies from arthritis patients and healthy donors and exposed them to bacteria with citrullinated proteins. The antibodies from the arthritis patients, but not the healthy donors, bound to them. This suggests that invasion by oral bacteria stimulates immune cells to release ACPAs that bind to both the bacteria and human joint proteins — the latter of which triggers a rheumatoid arthritis flare-up.

ACPAs often precede the onset of arthritis by years and are believed to contribute to joint tissue deterioration long before symptoms emerge. Therefore, preventing or limiting the production of ACPAs could help treat rheumatoid arthritis and be utilized in other diseases in which ACPAs are known to play a role, such as psoriatic arthritis and pulmonary tuberculosis.